No guarantee of easy recovery

One interesting feature of the economic downturn has been the changing attitude of the banking world to risk. Most solicitors will have involvement with the banks in one form or another. Extra and increased security for lenders seems to be the order of the day. In particular, lenders are very keen on the idea of debts being guaranteed by third parties whom they deem to have reliable asset strength. In its most common form this type of security will see company directors (or indeed their spouses) granting personal guarantees over corporate debts.

Given that general practitioners often have to give independent advice in respect of personal guarantees, their increased use means they require to be understood by a wider audience than banking lawyers and litigators. The writer has previously dealt elsewhere with the issue of their increasing use, and indeed the consequences for the profession in advising on such guarantees (see: “The Road to Recovery: Pitfalls for Lender and Borrower”, 2010 SLT (News) 105).

There has been no decrease in enforcement activity relating to guarantees over the last couple of years. Their increased use has begun to spawn considerable numbers of litigations relating to the enforceability of guarantees. Many of these cases are in dependence before the courts. In the writer’s experience these litigations are often protracted because, especially in the case of “non-bank” personal guarantees, the documents can be badly drafted and are unspecific in their terms. Allegations of misrepresentation inducing signature are commonplace. There are therefore all of the usual lessons that litigators like to point out to drafters based on the hindsight that a courtroom offers.

Kipling v Dunbar Bank plc

For the benefit of non-court lawyers it may be worth explaining that, procedurally, decisions relating to the enforcement of personal guarantees do not always arise from court actions where lender is pursuing borrower. One would expect a guarantee document to be registered in the Books of Council and Session and to contain a warrant for summary diligence in its contents. That being the case, the lender will usually be entitled to serve a charge summarily. If the guarantor wishes to argue about the lender’s right to enforce, normally their recourse will be to petition the Court of Session to suspend the charge for payment and to grant interdict against the lender being able to do diligence.

Kipling v Dunbar Bank plc [2012] CSOH 40 was such a case, and is worth noting not only because it contains further analysis of how a court will view enforcement of a guarantee, but more importantly because it appears to go further than previous authorities in allowing interim suspension of a charge in circumstances where it appears the guarantor’s case for avoiding liability may be “factually improbable”. The practical significance of such a development should not be missed. As will be observed below, such a decision is likely to increase the possibility of a lender having to litigate a case to final judgment, resulting in significant delays and increased cost of recovery.

In this case Kipling had been involved with a company for which the lender provided banking facilities. He had previously granted a personal guarantee, when in 2010 new banking facilities were discussed. It was a condition of the lender making the further facility available that a new guarantee was signed. Kipling, through the company, it was claimed, only agreed to signing the guarantee on the basis that the bank had agreed through a lending manager not to enforce it (one wonders not only why the bank would have done that (Lord Drummond Young observes there is always the possibility of a “gratuity”), but also why it would have had to be signed at all in such a case). On the basis of such averments, interim suspension of the charge was granted.

Some time later, Kipling adjusted his case to explain that rather than the lender formally agreeing not to enforce the guarantee, they had, he said, simply not objected to a unilateral condition he had imposed which was to the effect that the signed guarantee was only being delivered on the basis it was not enforced.

To some extent the actual facts do not matter. It was argued for the lender that although interim suspension had been granted, given the adjustments, there was now no arguable case. The interim orders should, they said, be recalled to allow them to continue enforcement action under the guarantee.

Interim orders

Lord Drummond Young considered and rearticulated the general law on the granting and maintenance of interim orders. He did so in five general propositions which helpfully consolidate and summarise where the jurisprudence has reached. The propositions are succinct, and restating them is possibly more helpful than commentating on them:

“First, the court's decision on an interim order is not a conclusive determination of the parties’ dispute, and in particular does not conclusively decide any factual question that arises in that dispute.

“Secondly, the orders under consideration are merely temporary orders; they are a holding operation, pending final determination of the dispute between the parties.

“Thirdly, because of the two foregoing factors, in any motion for the grant or recall of an interim order the court must give consideration to the balance of convenience. By this I mean the prejudice that may occur to each of the parties in the event that an interim order is made or recalled. That requires a judgment as to both the likelihood and the seriousness of such prejudice.

“Fourthly, the relative strength of the cases put forward by the parties in averment and argument is important; this means that the court must consider the cogency of the legal and factual case that is said to justify the interim order...

“Fifthly, the relative strength of the case that is said to justify an interim order must always be weighed with balance of convenience in the sense of likely prejudice. If the likely prejudice in the absence of an interim order is manifest and serious, an interim order may be justified even on the basis of a relatively meagre legal and factual case. It is, moreover, relevant to consider the prejudice to the respondent if an interim order is maintained until the final determination of the case; if that prejudice is relatively slight the continuation of an interim order may be justified even when the petitioner has put forward a case that appears on balance to be somewhat weaker than the respondent’s case. In every case, however, the critical task for the court will be an evaluation of the cogency of the parties’ cases and the likely prejudice to each party according to whether or not an interim order is granted or maintained.”

It is this fifth factor which not only weighed heavily in the present case, but is arguably going further than the courts have before (here in relation to prejudice to a borrower).

The decision

Lord Drummond Young effectively concluded that although on an interim basis the lender had a stronger case than Kipling, he could not say that the petitioner's case would fail at proof (self-evidently a high test). He judged that the prejudice of recall to the guarantor was so great that the interim orders should remain in place until proof.

Consequences

Looking at matters as a whole, what general conclusions can be reached? One can understand why the judge reached the view he did. There is considerable potential prejudice to the debtor in allowing recall of interim suspension (however, it should be borne in mind that the bench did seem to accept that the respondent’s case was the stronger). Lord Drummond Young also seems to have been influenced by the fact that the proof in this case was already fixed for a number of weeks after the recall hearing (which may be a point that allows this case to be distinguished in due course). However, underneath the attractiveness of a simple approach (that is to say simply measuring potential prejudice to both parties), is there a deeper policy issue that requires to be considered?

The writer would freely admit to seeing one side of the argument; he primarily acts for creditors seeking to enforce guarantees. However, trying to look at matters dispassionately, the difficulty if the Scottish jurisprudence continues to develop in this way is that lenders may well begin to question the utility of a personal guarantee, in terms either of allowing expeditious recovery, or generally its cost effectiveness in providing another form of security.

One would have to be careful not overstate the risks, but the point is perhaps best made dealing with an extreme example: if any director who granted a personal guarantee is going to be able to avoid liability under it for a number of years (even when his case is objectively weak), while a case finally makes it toward proof (and meantime costing the lender significant sums in legal expenses while the guarantor does not have to find caution – another feature of the decision), personal guarantees will probably be used less.

While that might sound attractive, when one considers that guarantees are often a security of last resort it does not seem far fetched to conclude that fewer personal guarantees may mean less lending. On balance, and given the need to have an expeditious way to enforce recovery of sums that are contractually due, it would be useful in future to see the courts recognising the wider policy interests for the benefit of lender as well as guarantor.

In this issue

- Data protection principles and family practice

- Data protection: another generation

- No guarantee of easy recovery

- Forced marriage: alive to the issue

- Mediation: business as usual?

- Electronic payments and electronic money

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion column: Gillian Mawdsley

- Council profile

- Book reviews

- President's column

- Caution the souvenir hunters

- Together we thrive

- But you said...

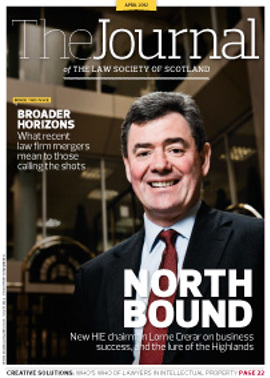

- Heart in the Highlands

- Cut the lockup cost

- Who's who in intellectual property

- Taking liberties with bail

- Personal licences: a need for review?

- TUPE: fair or unfair for staff?

- 10%: a real gain?

- Renovating home PDRs

- Ademption and powers of attorney

- Working group to take forward ILG review

- Law reform roundup

- From the Brussels office

- Feedback, take 2

- Chinks in your defences?

- Business checklist

- Ask Ash