Opinion column: Gillian Mawdsley

Growing world trade, and technological developments such as the printing press, led to the creation of intellectual property (IP) rights – copyright and trade marks – several centuries ago. Fast forward to 2012 and the London Olympics, when 21st-century globalisation and online communications have further changed our culture.

Our insatiable consumer appetites for the latest “must-have” products foster, support and encourage the abuse of IP rights. I want a London 2012 T-shirt. What do I care if one of the Games’ marks (defined as the official names, trade marks or logos) is used on my T-shirt without consent of the IP rights holder?

In fact, IP rights are enforceable in both civil and criminal courts. Civil proceedings are often unattractive to the rights holders, as litigation is complex, lengthy and expensive. Even if successful, the accused often turn out to be “men of straw”, and decrees prove ineffective. Criminal enforcement of IP rights – prosecution of “IP crime” – is set out in the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Trade Marks Act 1994. In Scotland, the COPFS is, of course, responsible for prosecutions in the public interest. No figures exist as to the number of prosecutions taken to court in Scotland, as IP crime is included as crime against business, which costs at least £15bn a year in the UK. But should the criminal courts act as debt collectors for the sportswear or film industries?

We often perceive abuse of IP rights as neither criminal nor even immoral. It is seen as a victimless crime. The companies involved are giant, fabulously wealthy multinationals; Adidas, for instance, is the Games’ mark sportswear brand owner. The public have little interest in criminal enforcement, and we live in a time of swingeing budget cuts. Should Government allocate scarce resources to dealing with IP crime?

Well, the Scottish Government is committed to “a safer and stronger Scotland by protecting [us]... from threats to... safety and prosperity”. IP rights have to do with more than just the logo on my T-shirt. The purchase of a counterfeit T-shirt or a pirated DVD can be seen against the purchase of fake medicines or foodstuffs, which can cause sickness or death. Unregulated manufacture of counterfeit goods can mean the exploitation of workers, or child labour in dangerous working environments. IP crime affects Government by loss of revenue from VAT and taxes, and has links to organised crime. IP crime threatens our economic recovery. When businesses are affected, so is economic growth. The criminal gain in the UK in 2006 from IP crime was estimated at £1.3 billion, with £900 million flowing to organised crime. That also translates to job losses in the UK.

For criminal prosecutions to be successful, a combination of actions is required. Effective investigations need to be reported by FACT (anti-counterfeiting), BPI (recorded music) and other enforcement agencies with admissible evidence. They need experienced prosecutors with detailed legal understanding of IP crime; they need statutory crimes to fit today’s advanced technology; and they need judicial sanctions with sufficient penalties to deter what has sometimes been trivialised as “white collar” crime.

Criminal enforcement alone, however, is too narrow an approach to IP abuse. Public campaigns educate by raising awareness. Recall the Crimestoppers’ “Fake goods fund crime” campaign about the impact of my T-shirt purchase, or the barrage of FACT adverts in the cinema. Though the law is still playing catchup, effective and high-profile prosecutions have taken place in Scotland, for example when Christopher Clarke was sentenced to 160 hours’ community service for camcorder piracy in a cinema. More seriously, targeting assets acquired through IP crime under the Proceeds of Crime (Scotland) Act 1995 can halt the flow of cash from such offences.

The UK Government’s attitude to abuse of IP rights has become much more focused recently, with greater funding. A framework for action has been provided in “Prevention and Cure: The UK IP Crime Strategy 2011”, published by the Patent Office last summer. Government involvement should come as no surprise, at a time when all eyes are focused on London 2012 as a global landmark event.

Being seen to have a strong enforcement regime is important. It encourages enormous economic returns and investment for the UK. Companies sponsoring London 2012 want the return on their investment to be protected, with actions to prevent their exclusive rights being undermined or devalued.

2012 is not the time for London to be described as “the counterfeiting capital” – a term applied to the Glasgow “Barras” in the 1990s. What about the XX Commonwealth Games, to be held in Glasgow in 2014?

Gillian Mawdsley is a former fiscal depute. She is a legal consultant in the Judicial Studies Committee and a tutor in IP Law at the University of Strathclyde. The views expressed are not necessarily those of either organisation.In this issue

- Data protection principles and family practice

- Data protection: another generation

- No guarantee of easy recovery

- Forced marriage: alive to the issue

- Mediation: business as usual?

- Electronic payments and electronic money

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion column: Gillian Mawdsley

- Council profile

- Book reviews

- President's column

- Caution the souvenir hunters

- Together we thrive

- But you said...

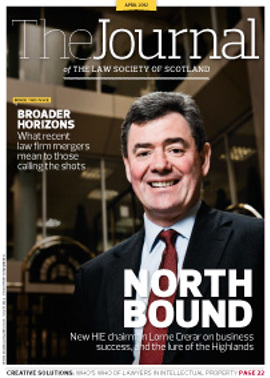

- Heart in the Highlands

- Cut the lockup cost

- Who's who in intellectual property

- Taking liberties with bail

- Personal licences: a need for review?

- TUPE: fair or unfair for staff?

- 10%: a real gain?

- Renovating home PDRs

- Ademption and powers of attorney

- Working group to take forward ILG review

- Law reform roundup

- From the Brussels office

- Feedback, take 2

- Chinks in your defences?

- Business checklist

- Ask Ash