Taking liberties with bail

Bail condition “Not law”

Criminal practitioners are still coping with the impact of the appeal court’s decisions in Cameron v Procurator Fiscal, Livingston [2012] HCJAC 19 and [2012] HCJAC 31.

In summary, the two opinions delivered on 8 and 14 February 2012 dealt with the legality of s 24(5)(cb) of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995, a further standard condition of bail inserted by s 58 of the Criminal Justice and Licensing (Scotland) Act 2010. The amendment made it a standard condition of any bail order that the accused, whenever reasonably instructed by a constable to do so, (i) participates in an identification parade or other identification procedure; and (ii) allows any print, impression or sample to be taken from him.

In declaring under s 29 of the Scotland Act 1998 that this amendment was “not law”, because its mandatory nature was incompatible with article 5 of ECHR and could not be read down to make it compatible, the court (in the course of its first opinion) examined the structure and interpretation of article 5, concluding that pre-trial detention was only compatible with the right to release where that detention was for the purpose of avoiding a number of real risks, including flight, interference with witnesses and the commission of further offences.

Crucially, these and other risks had to be of a kind which justified pre-trial detention and which could not be averted or reduced by the imposition of bail conditions. To subject pre-trial release to the acceptance of a proposed bail condition for which detention could not be justified must, in principle, engage the right to liberty under article 5. It was therefore necessary for a judge considering the imposition of a particular bail condition to consider individually whether that proposed condition addressed and was properly related to one of the enumerated risks.

In the present case, by making mandatory the condition in question, the legislature had removed from the court any consideration of the necessity of the condition. While the need for evidence-gathering might (in particular circumstances) justify short-term detention, the issue of whether that could be made the subject of a bail condition would require to be assessed in each separate case.

The court’s second opinion dealt with retroactive effect under s 102 of the 1998 Act. Happily for the Crown, this was limited (broadly) to “live” cases; one can still hear the sighs of relief.

Reasonable time to judgment

In the February issue, attention was drawn to the five-judge decision in Gemmell v HM Advocate [2011] HCJAC 129, which reviewed a number of aspects of sentence discounting. One of the other significant features of that appeal is the fact that it was taken to avizandum on 23 June 2010 but judgment was not delivered until 20 December 2011, some 18 months later.

That fact led to further proceedings on the question of delay and on 27 January 2012, it was held that in the case of four of the appellants there had been a breach of the “reasonable time” guarantee in article 6 of ECHR. The full reasons for that decision are now to hand: McCourt and Robertson v HM Advocate; Ross v Procurator Fiscal, Aberdeen; Hart v Procurator Fiscal, Alloa [2012] HCJAC 32.

Under reference to the relevant ECtHR jurisprudence, the court emphasised that for the purposes of article 6, time runs from the point of “charge” until the final conclusion of the proceedings, including any appeal. Further, while the whole period may not seem excessive, an unduly lengthy stage of the proceedings might show the lack of diligence required to meet the obligations of the state. The reasonableness of the length of the proceedings depends on the whole circumstances, with reference to the complexity of the case, the conduct of the accused and the relevant authorities, and what was at stake for the affected person.

Applying these principles to the four cases, the court rehearsed the whole procedural history of each, noting that in none of them was a complaint made about the length of the proceedings prior to the appeals being taken to avizandum. Indeed, there was a rule of thumb that all cases taken to avizandum, civil or criminal, should be advised within three months of the hearing, although there are exceptional cases which, for reasons of complexity or otherwise, would justifiably take longer. The court then considered the relevant factors bearing on the 18-month period, before concluding “without much difficulty” that in each case the proceedings had not been completed within a reasonable time. In the result, each of the already discounted penalties was reduced further as just satisfaction.

Prior witness statements

Where in a criminal trial the Crown seeks to take advantage of s 260 of the 1995 Act, whereby any prior statement made by a witness is admissible (subject to certain conditions) as evidence of any matters stated in it of which direct oral evidence by him would be admissible if given in the course of those proceedings, the evidential picture can become very confused if the parties do not clearly appreciate both the purpose of the exercise and how the section is meant to operate. In the result, the task of the trial judge in charging the jury can be made more difficult, especially if the distinction between the respective roles of s 260 and the common law rules first stated in Muldoon v Herron 1970 JC 30 and developed in Jamieson v HM Advocate (No 2) 1994 SCCR 610 has become blurred.

Such was the situation in A v HM Advocate [2012] HCJAC 29 (21 February 2012), where the appeal court quashed the conviction of an accused charged with serious assault. The issue at trial was corroboration of the identification of the accused as the assailant, the complainer having identified him unequivocally. A number of directions were given to the jury by the presiding judge as to the evidential value of certain prior statements made by purportedly corroborating Crown witnesses, but at the appeal the Crown conceded that the jury had been misdirected, arguing however that there had been no miscarriage of justice. This was rejected by the court, which unanimously allowed the appeal.

But the interest in the case is not so much the result but the fact that the judges (particularly Lords Bonomy and Emslie) spent some time examining the import of both the common law and the whole statutory provisions on the use of prior witness statements in criminal trials in Scotland and, in particular, one of the requirements of s 260: that the witness must “adopt” his earlier statement: s 260(2)(b). Whether the witness has done so in any particular case is a matter for the jury, not a matter of law for the trial judge. Great care needs to be taken when applying this and the other rules to the evidence not just of a forgetful witness, but one who is vacillating, reluctant or deliberately evasive. This is a situation with which all those involved in criminal trials have become all too frequently aware.

No discount on s 16 order

Another piece of the discount jigsaw has fallen into place with the decision in Ottaway v Procurator Fiscal, Dundee [2012] HCJAC 36 (14 March 2012). There, the appeal court refused an appeal against a decision by the sheriff that no discount should be applied to a s 16 order that the accused should serve three months of the unexpired portion of an earlier custodial sentence before serving his sentence for new offences committed during the time he was at liberty.

Indeed, the argument that s 196 of the 1995 Act was wide enough to permit the application of a discount in s 16 cases received very short shrift indeed, for no less than seven reasons were enumerated for rejecting it: (i) the potential for a s 16 order arises automatically without the necessity for any proof or plea; (ii) the maximum potential length of the order is the same whether the fresh conviction proceeds on a plea of guilty or after trial; (iii) the maximum potential return period will often be restricted where a discount was allowed on the original sentence; (iv) the making of a s 16 order and the passing of a new sentence are separate and distinct processes; (v) what merits a discount on a plea of guilty is the objective utilitarian value of the plea, something which does not apply in the case of a s 16 order; (vi) the terms of s 196(1A) are directed to the “passing” of sentence under the 1995 Act, unlike the different statutory basis of a s 16 order; and (vii) s 196 deals with sentences for offences, rather than the breach of trust which renders a released offender liable to return to prison.

But, as the court observed, a s 16 order is still a “sentence” for the purposes of the Prisoners and Criminal Proceedings (Scotland) Act 1993 and brings into play the early release provisions of that Act.

In this issue

- Data protection principles and family practice

- Data protection: another generation

- No guarantee of easy recovery

- Forced marriage: alive to the issue

- Mediation: business as usual?

- Electronic payments and electronic money

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion column: Gillian Mawdsley

- Council profile

- Book reviews

- President's column

- Caution the souvenir hunters

- Together we thrive

- But you said...

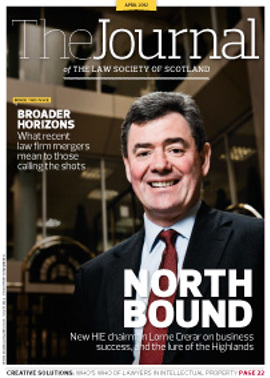

- Heart in the Highlands

- Cut the lockup cost

- Who's who in intellectual property

- Taking liberties with bail

- Personal licences: a need for review?

- TUPE: fair or unfair for staff?

- 10%: a real gain?

- Renovating home PDRs

- Ademption and powers of attorney

- Working group to take forward ILG review

- Law reform roundup

- From the Brussels office

- Feedback, take 2

- Chinks in your defences?

- Business checklist

- Ask Ash