Book reviews

No Ordinary Court

100 Years of the Scottish Land Court

PUBLISHER: AVIZANDUM

ISBN: 9781904968511

PRICE: £16.95

The Scottish Land Court is 100, and to mark this significant milestone a book has been published: No Ordinary Court. For anyone who practises in crofting or agricultural law, this book is thoroughly enjoyable and will fill any gaps in knowledge that may exist concerning the workings of the court. But you don’t have to be a lawyer to enjoy this book. It is filled with anecdotes that will raise a smile on anyone with even a passing familiarity of life in the Highlands & Islands and/or the Scottish Court Service.

In his forward, the Rt Hon Lord Gill made me want to fast forward to the chapter by Lord McGhie on "The Gibson Years". However, I was restrained and read the book in its chronological order.

James Hunter provides a stirring account of the court’s revolutionary origins. He takes us back to 1882 and the clash between crofters in Skye and policemen brought in from Glasgow to apprehend those crofters who had breached eviction orders served on them by a sheriff officer. This was "The Battle of the Braes", with the police being pelted with stones, rocks and other missiles, that led to the inquiry by the Napier Commission.

What I hadn’t fully appreciated was the fact that the Napier Commission’s recommendations created more unrest and the establishment of what became the Highland Land League. They succeeded in sending their own pro-crofter MPs to Parliament and those MPs, in turn, with the backing of Irish Nationalist MPs, gave us the Crofters Holdings (Scotland) Act 1886. This gave crofters security of tenure and the right to fair rents. The Crofters Commission originally had jurisdiction for fixing fair rents, but its duties in this and other respects were transferred in 1912 to the Scottish Land Court by virtue of the Small Landholders (Scotland) Act 1911.

Keith Graham, former principal clerk to the court, then tells us about the court’s first year. I found it interesting to learn that, back then, the sheriff clerks throughout Scotland acted as local agents for the Land Court, with applications being lodged with and intimations made by the sheriff courts. In the beginning the court was clearly a “user friendly” one, a feature that has pleasantly continued throughout its 100 years and makes it a somewhat special court.

However, as we learn from Ewen Cameron in his chapter on the court to 1955, the early years had the court regarded with great suspicion, due to the extension of security of tenure from the seven crofting counties to the remainder of Scotland. The court was in 1914 referred to as “the new tyrants of the countryside” by The Scotsman, and as the “Agrarian Star Chamber” by Blackwood’s Magazine. The court was also not without criticism during that period from the Court of Session on appeals, particularly as a result of “the style and rhetorical indulgence” of its chairman, Lord Kennedy.

Walter Mercer then takes us through the pre-Gibson chairmen, from the eccentric Lord Kennedy to the professional “butterfly” Lord Murray, via the diligent Lord St Vigeans and the criminal silk Lord Macgregor Mitchell.

Then we come to the much anticipated Gibson Years, by Lord McGhie. This is indeed a colourful chapter on Lord Gibson’s eccentricities. There are numerous anecdotes of Lord Gibson’s self importance, but the cornerstone of this chapter, which tells the story of the spoof mace, had me laughing out loud and my wife asking “How is a book about a court funny?”

Walter Mercer then brings us up to date with details of the post-Gibson chairmen. This takes us from Lord Birsay (the kilt-wearing Orcadian) to the current chairman, Lord McGhie, via Lord Elliott (who was not well disposed to Gaelic) and Lord Philip (who “ran a happy ship”).

Keith Graham then runs through the members of the court, with some interesting details such as the member who raised a court action against the Lord Advocate on the basis that the condition that members should vacate office at the age of 65, or earlier if incapacitated by ill health or otherwise, was ultra vires. James E Esslemont, the member in question, was successful, resulting in the Scottish Land Court Act 1938 being passed the following year imposing a statutory retirement age of 65 on all members except the chairman.

One of the members of the Land Court must be able to “speak the Gaelic language”. Sheriff Roderick J MacLeod takes us through the history of Gaelic in the court. Whilst not used that often (with there being an apparent preference for English), there have been notable instances when it has been. Sheriff MacLeod quotes Colin MacDonald (who was a Gaelic speaking member of the court) as saying: “on the tongue of the master, the finer shade of expression in the Gaelic can be so much more effectively applied to his purpose”.

Keith Graham gives an amusing account of the Rocket Range cases, where the Air Ministry required resumption of land from crofting tenure for a guided missile range in the Outer Hebrides in the 1950s. The Land Court hearing was presided over by Lord Gibson, who agreed to grant resumption subject to conditions. These were that the range should be operated by a regiment speaking exclusively Gaelic, and that the regiment should wear a special uniform with tartan trews which would be designed by a friend of his in Lochboisdale. “This time”, announced Gibson, “we can make the Western Isles the Gaelic-speaking area that it was in Bruce’s time”. Following the influence of other members of the court that evening, the following day Lord Gibson withdrew his remarks unreservedly, with resumption being granted unconditionally.

Isabel Steel, former deputy clerk to the court, then takes us on a tour of circuit life – "From Horse to Helicopter". This chapter tells us about the peripatetic nature of the court, the only one in Scotland that “goes to the people”. Isabel points out the importance of inspection of the ground by expert members. Often this means long spells away from home for members of the court. In the summer of 1913 a divisional court sat in Shetland for three months, taking only Sundays off and even sometimes travelling on those. Isabel gives a colourful account of the various means of transport used, from rowing boats to a helicopter. She recounts being treated to a magnificent display of the Northern Lights, “blood red and covering the whole sky”. I remember that night very well indeed as I was also in Shetland for the hearing that brought the Land Court there. We hear from Isabel of encounters with a stick-wielding crofter, and dogs and cats causing members of the court sleepless nights.

Isabel Steel continues with the next chapter of the book, this time on "Cherish Your Staff". She recounts the staff who worked at the court over the years and who have, on the whole, been loyal and longserving employees, usually only leaving on retirement. An interesting fact was that in the early years of the court the subsistence allowances paid to the employees often did not cover their expenses when on circuit. Despite protestations by Lord Kennedy, he was generally unsuccessful in having allowances increased. That does not appear to be a problem today. Another interesting fact is that since 2010 there has been no typist with each member of staff, and members of court having to do their own word processing. Something that, indeed, is becoming more common in law firms as well.

In the next chapter Sir Crispin Agnew QC looks at the agricultural holdings jurisdiction of the Land Court, with detailed reference to the relevant statutory provisions and case law.

The penultimate chapter gives a recollection of court life from various authors, including retired members of the court and their families. I raised a smile when Catherine Montgomery (daughter of Murdo Montgomery, a member of the court from 1947 to 1963) told us that her father “used to say, with amusement, that in spring a young man’s thoughts may turn to thoughts of love but in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland they turn to grabbing his neighbour’s land”. The stuff of many a Land Court case, and one that I am currently actively involved in! Being a Shetlander, I enjoyed John Kinloch recounting his work for the court in one of his “favourite parts of the world”.

The book concludes with David Houston, a current member of the court, "Taking Stock". In this chapter David looks at the court today and the future into its second century. He tells us of the decline in circuit cases, which have dwindled to a trickle. The reasons for this are not clear although David wonders if we will see an increase when the map based Crofting Register is introduced later this year. Despite this, there has been an increase in workload arising from the Agricultural Holdings (Scotland) Act 2003, resulting in the secondment of Sheriff MacLeod as deputy chairman. David discusses alternative dispute resolution, but concludes that there will still be a place for this extraordinary court in its second century.

No Ordinary Court: 100 Years of The Scottish Land Court can be purchased from The Scottish Land Court, 126 George Street, Edinburgh by sending them a cheque for £15 with a note of your name and address.

Human Rights Law in Scotland

3rd edition

Robert Reed and Jim Murdoch

PUBLISHER: BLOOMSBURY PROFESSIONAL

ISBN: 9781847665560

PRICE: £95

The first edition of this essential work was published in 2001 and the second edition in 2008.

This edition follows closely upon the previous one, but such is the development of certain aspects of human rights law that recent developments since the Cadder case, notably in Jude v HM Advocate [2011] UKSC 55 and Ambrose v Harris [2011] UKSC 43, involving waiver and detention, are not covered. Similarly, the approach to devolution issues taken by the Supreme Court in Fraser v HM Advocate [2011] UKSC 24 is at odds with the statement by the learned authors at p 90, footnote 5.

The law is stated as at 31 March 2011.

The authors cover this vast topic from both civil and criminal law perspectives in a highly readable fashion. Not many practitioners have access to a full set of European Court judgments, and at times it can appear daunting to find the right lines of authority through web searches. This book helps the reader focus on the principles and from there follow up the detail in the appropriate cases. The text is fully and clearly vouched, with footnotes on each page. The tables of cases referred to in the text are gathered together in domestic and international groups for ease of reference.

After three very comprehensive introductory chapters which provide a clear overview, the various articles of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms are dealt with individually. The book also includes a copy of the Human Rights Act and relevant sections of the Scotland Act 1998, together with a copy of the Convention.

Although it is a substantial book, it is very readable and in a handy form for easy access, yet rewards fuller study.

In this issue

- Trapped by the Wildlife Act?

- What constitutes "reasonable endeavours"?

- Reflective learning explained

- Values to the fore

- Employee ownership: removing the barriers

- Reading for pleasure

- Should you be paying your interns?

- Opinion column: John Deighan

- Book reviews

- Council profile

- President's column

- Edinburgh's history unveiled

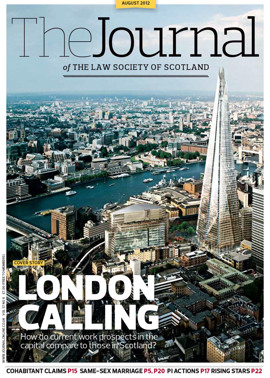

- Capital connection

- Cohabitees and the principle of fairness

- Coulsfield cloned

- A plea in law for equal marriage

- Aiming high: rising stars

- Get your facts right

- Pension rights and TUPE transfers

- 2014: an ET odyssey

- Giving back

- ILG to mark 40 years in style

- Rural lessons for urban conveyancing

- Investing in our own futures

- Training the flexible way

- Business radar

- Code of conduct for MHT work

- Law reform roundup

- The threat from within

- Ask Ash

- The learning curve