Cohabitees and the principle of fairness

On 4 July 2012, the UK Supreme Court issued judgment in the longlasting, widely publicised case of Gow v Grant [2012] UKSC 29.

The facts of the case are not unusual. Mr Grant and Mrs Gow met in 2001. In December 2002, Mrs Gow agreed to begin living with Mr Grant in his property on the condition that the couple became engaged. Prior to their relationship, both parties owned their own properties and were in employment.

In 2003, Mrs Gow sold the property in her sole name for £50,000, the proceeds being put towards the parties’ living expenses and to discharge her debts.

By 2009, Mrs Gow’s former flat had increased above the sale value by £38,000. When Mrs Gow’s employment ceased, she did not seek further work, at the request of Mr Grant. While cohabiting, the parties also bought two timeshare weeks in their joint names for approximately £7,000. Mrs Gow paid £1,500 towards the first week and the whole price for the second week.

In 2008, the relationship ended. Mrs Gow moved out of Mr Grant’s house into a rented property in 2009. Mrs Gow raised a court action in Edinburgh Sheriff Court seeking financial relief. She argued that she had been economically disadvantaged by having sold her home to move into Mr Grant’s property and that as a result, she had lost out on the rising value of her property during the years that followed.

Competing approaches

The sheriff was not prepared to adopt the approach under s 9(1)(b) of the 1985 Act, as there was no matrimonial property as such to be shared. In her view the court had discretion to make an order which was fair and not simply one limited to a sharing of property acquired during the relationship. It had been significant that Mr Grant had not suffered any economic disadvantage but Mrs Gow plainly had, as moving in with him was the only reason for her house being sold. Mrs Gow was awarded financial relief to the sum of £39,500 for the economic disadvantage she suffered during the cohabitation.

Mr Grant appealed to the Inner House and the sheriff’s decision was overturned. The court sidestepped giving any opinion on the construction of s 28, saying that this was not necessary beyond ensuring that the objective of the statute was attained. The court held that the objective was limited to consideration of clear and quantifiable economic imbalances that had arisen as a result of the cohabitation, rather than any wider issues that might have arisen between the parties. The court concluded that the evidence had not supported an award being made under s 28: the prerequisite that the house had been sold by Mrs Gow in the interests of Mr Grant had not been met, and if she had suffered economic disadvantage, that had been offset by economic advantage derived from his contribution to joint living expenses during the cohabitation.

Mrs Gow appealed to the Supreme Court. This time the appeal did centre on the interpretation of s 28. The court looked into the background to the 2006 Act, tracing its path through the Law Commission and Parliament and concluding that the emphasis was very much on fairness between cohabiting couples, despite the absence of the words “fair and reasonable” in the section. The rebuttable presumption at the end of a cohabitation relationship was that the cohabitees each retained their own property.

“Natural meaning”

In his judgment, Lord Hope stated that “it would be wrong to approach s 28 on the basis that it was intended simply to enable the court to correct any clear and quantifiable economic imbalance that may have resulted from the cohabitation. That is too narrow an approach.… a claim based on contributions or sacrifices in non-commercial relationships… cannot often be valued precisely”.

Lord Hope acknowledged that the phrase “in the interests of the defender” could be taken to mean “in a manner intended to benefit the defender”. However, he affirmed that “it does not compel that interpretation, and in the present context, where the guiding principle is one of fairness [between both parties], its more natural meaning is directed to the effect of the transaction rather than the intention with which it was entered into”.

The question for the sheriff had been whether at the end of the exercise directed by s 28, the applicant was left with some economic disadvantage for which an award might be made, and the Inner House had lost sight of Mrs Gow’s argument that she had lost the benefit of the increase in value of her principal capital asset.

Therefore, it did not matter that Mrs Gow had benefited from the sale proceeds of the house as well as Mr Grant, or that she had not sold the house for the purpose of Mr Grant deriving direct benefit from the proceeds.

The unfairness and economic imbalance between the parties when they separated were the clear factors in the Supreme Court’s decision.

The Inner House decision was overturned and the award of financial relief to the sum of £39,500 was reinstated for the economic disadvantage Mrs Gow suffered during the cohabitation.

Looking forward in Scotland

The Family Law (Scotland) Act 2006 has been in force for a number of years now, but this decision provides clarification for Scottish family lawyers following a number of contradictory outcomes in the lower courts. It gives fresh hope too that there is still scope for a fair outcome in cohabitants’ claims, where practitioners had begun to wonder before the decision how it would ever be possible to make meaningful use of the Act.

I did read one commentary which implied that the decision had implications for friends who lived together, but the commentator seems to have overlooked s 25 of the Act which clearly defines a cohabitant as a member of a couple who live together as if they were husband and wife.

Lord Hope has made it clear that s 28 of the 2006 Act does not seek to replicate the financial relief provisions for a divorcing couple under s 9 of the Family Law (Scotland) Act 1985. Continuing financial support or a property sharing regime should not be imposed on a cohabiting couple whose relationship has broken down, but fairness in the application of s 28 must be considered.

I do wonder whether, as is entirely possible in the current climate, if Mr Grant’s property value had dropped during the period of cohabitation and Mrs Gow had wisely preserved her sale proceeds in a savings account, Mr Grant would have been able to ask for an award from Mrs Gow on the basis of fairness!

Advice for England

Although the judgment was written by Lord Hope, Lady Hale added “a few words because there are lessons to be learned from this case in England & Wales”. If the case had arisen there, Mrs Gow would probably have received nothing.

Lady Hale called for law reform in cohabitation law in England & Wales, based on the “principle of compensation for the economic advantages and disadvantages resulting from the relationship”. She noted that injustice can result under the current law, where parties may be penalised as a result of a lack of recognition of any contributions made during the time of cohabitation.

She also noted that it is very difficult to work out who has paid for what and who has enjoyed what benefits over the course of the relationship, but she did state that: “It is much more practicable to consider where they were at the beginning of their cohabitation and where they are at the end, and then to ask whether either the defender has derived a net economic advantage from the contributions of the applicant or the applicant has suffered a net economic disadvantage in the interests of the defender or any relevant child.”

At the conclusion of her judgment, Lady Hale summarised that: “The main lesson from this case, as also from the research so far, is that a remedy such as [the Scottish remedy] is both practicable and fair. It does not impose upon unmarried couples the responsibilities of marriage but redresses the gains and losses flowing from their relationship… As the researchers comment, ‘The Act has undoubtedly achieved a lot for Scottish cohabitants and their children’. English and Welsh cohabitants and their children deserve no less.”

Lady Hale compared the reforms proposed by the Law Commission’s report, entitled “Cohabitation: the Financial Consequences of Relationship Breakdown”, to the Scots cohabitation law and made several of her own proposals. However, it is unlikely that we will see any reform in cohabitation law in England in the near future, as the Government never agreed with the Commission’s recommendations and in 2011 it announced that the research failed to provide grounds for law reform in this area.

In this issue

- Trapped by the Wildlife Act?

- What constitutes "reasonable endeavours"?

- Reflective learning explained

- Values to the fore

- Employee ownership: removing the barriers

- Reading for pleasure

- Should you be paying your interns?

- Opinion column: John Deighan

- Book reviews

- Council profile

- President's column

- Edinburgh's history unveiled

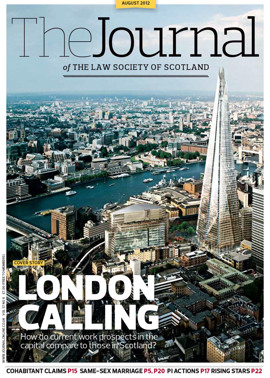

- Capital connection

- Cohabitees and the principle of fairness

- Coulsfield cloned

- A plea in law for equal marriage

- Aiming high: rising stars

- Get your facts right

- Pension rights and TUPE transfers

- 2014: an ET odyssey

- Giving back

- ILG to mark 40 years in style

- Rural lessons for urban conveyancing

- Investing in our own futures

- Training the flexible way

- Business radar

- Code of conduct for MHT work

- Law reform roundup

- The threat from within

- Ask Ash

- The learning curve