Coulsfield cloned

On 1 September 2012, the Act of Sederunt (Summary Cause Rules Amendment) (Personal Injuries Actions) 2012 (SSI 2012/144) brings into force new rules and procedures for summary cause personal injury actions in the sheriff court. This represents the latest step in the move towards uniformity of rules for personal injury actions in Scotland based on the court timetable approach.

Cloning Coulsfield

The simplified procedure for personal injury actions (Court of Session Rules, Chapter 43) was introduced in the Court of Session in April 2003 following the recommendations of a working party chaired by Lord Coulsfield. It aimed to eliminate unnecessary procedure, delay and expense. The procedure proved successful, and following a consultation by the Sheriff Court Rules Council on proposals for a similar procedure in the sheriff court, new “Coulsfield” ordinary cause personal injury rules came into force in November 2009 (see the author’s article at Journal, October 2009, 20).

These have met with general approval. Primary legislation would, however, be required to remove personal injury actions from summary cause procedure, to allow one set of rules to govern all sheriff court personal injury actions, and the changes to the privative and summary cause limits introduced in January 2008 have meant that a significant number of personal injury cases now fall within the summary cause range.

It is recognised that the value of a personal injury claim is not necessarily proportionate to its complexity or the amount of time spent pursuing or defending it, and it is therefore desirable to try to attain consistency of procedure for all sheriff court personal injury cases.

A new Chapter 34

Existing summary cause rules already have their own designated procedure for personal injury cases, in Chapter 34. However, the recent increase in volume of such actions has highlighted difficulties with the practical application of these rules, leading many practitioners to pursue actions as ordinary causes, even where the potential value falls firmly within summary cause limits.

Difficulties include the requirement to produce an often meaningless statement of valuation of claim at the outset, before recovery of necessary evidence such as wages information; the absence of any opportunity to adjust the statement of claim or form of response; the inconsistent way in which calling dates are dealt with from court to court; and the variable time periods within which proofs are assigned. Moreover, it was recognised that the case management approach of existing summary cause procedure was not applied consistently, and is at odds with the timetable-based approach which has proved so successful under Coulsfield procedure.

As it was not possible to remove personal injury actions from summary cause procedure, it was considered that the best approach was to rewrite Chapter 34 to try to incorporate Coulsfield into existing summary cause structure. The key points are summarised in the panel opposite.

Form of summons

The standard summary cause summons (Form 1) is retained. The form of claim to be inserted in box 4 is the standard form of claim in a summons for payment of money. However, the new rules specifically provide that instead of stating the details of the claim in box 7, a pursuer now requires to attach to Form 1 a separate statement of claim in Form 10. This is similar to that required under existing Chapter 34 procedure, and is consistent with the simplified pleadings which underpin Coulsfield procedure.

The purpose is to achieve brevity and clarity of pleadings; however, the rules of relevancy and the requirement to give reasonable notice of your case remain. The summons may include a specification of documents (Form 10b) which contains the same standard paragraphs as in ordinary procedure, and for which commission and diligence is automatically granted when the summons is authenticated.

Service and response

When the summons is authenticated by the sheriff clerk, a return date and calling date are assigned. There are new defenders’ copy summons, Form 1e (where a time to pay direction may be applied for) or 1f (in every other case), which replace existing Forms 1a and 1b. These forms clarify the new procedure to be followed if the defender wishes to defend the action.

A separate form of response, Form 10a (based on existing Form 10b) requires to accompany every service copy summons. This sets out a list of questions which must be answered by the defender. The completed form represents the defender’s “pleadings”. If a defender wishes to challenge jurisdiction, defend the action or state a counterclaim, they require to complete and lodge with the sheriff clerk the relevant section of the defender’s copy summons (Form 1e or 1f) in addition to the completed Form 10a. As with the pursuer, the defender is obliged to provide fair notice of the grounds of fact and law of their defence.

Once received, the sheriff clerk intimates to the pursuer a copy of the defender’s form of response, discharges the calling date, allocates a diet of proof (no later than nine months from the date of first lodging of the form of response), and issues a timetable setting out the procedural milestones of the action.

Case management by timetable

One of the biggest changes from existing summary cause procedure is that in a typical case, if all elements of the timetable are complied with, there is no requirement for the case to call in court at any stage prior to proof. The timetable acts as a template and sets out the case flow for each individual case. It specifies dates or milestones, which will be familiar to ordinary cause personal injury practitioners, for each stage of procedure to be complied with. The timetable must be strictly adhered to. It is treated for all purposes as an interlocutor signed by the sheriff.

Certain failures to adhere to the timetable will automatically result in a hearing being fixed before the sheriff for parties to explain themselves. Other breaches may cause the case to call at the sheriff’s discretion.

Adjustment and lodging of “pleadings”

The new rules recognise that in personal injury actions, it is often necessary to make changes to a statement of claim or form of response, consistent with the principle of fair notice, to reflect further evidence or information received or to respond properly to a position being adopted by the opponent, for example to respond to an allegation of contributory negligence or provide further notice of common law or statutory breaches in light of documentation recovered.

Likewise, it is not uncommon for defenders’ agents only to be afforded an opportunity to commence detailed investigations when they receive papers from their instructing insurers. The nature of their defence may change after initial enquiries are undertaken.

The timetable provides that both parties have until not later than eight weeks after the form of response has been lodged to adjust their respective statement of claim or form of response. By the expiry of that period, the pursuer is obliged to lodge a statement of valuation of claim (the defender has a further four weeks to lodge their own statement of valuation).

Not later than 10 weeks after the form of response has been lodged, the pursuer requires to lodge a “certified adjusted statement of claim”, and the defender (or any third party) to lodge their own “certified adjusted response to a statement of claim”.

Because there is no such thing as a record in summary cause procedure, it is necessary for both pursuer and defender to lodge a certified statement of their respective positions. The requirement to lodge a certified adjusted form of response is a new one which will be unfamiliar to defenders’ agents.

Incidental applications

It is the pursuer’s obligation when lodging the certified adjusted statement of claim to apply by incidental application to the sheriff, craving the court to allow a preliminary proof, a proof, or to make some other specified order. It is anticipated that if either party has an objection to the other side’s case as set out in their certified statements, whereby they do not believe the case should proceed to proof, this is the stage when they should intimate such objection, or opposition.

In this way, if any party believes their opponent is not providing fair notice of the case, or that there is a fundamental lack of relevancy, the sheriff has a wide discretion to decide the issue and apply whatever disposal is deemed appropriate. For administrative convenience, when intimating the incidental application, the pursuer is obliged to provide a note of the anticipated duration of the proof.

Pre-proof conferences

These require to take place not later than four weeks before the date assigned for a proof; a minute of the conference requires to be lodged no later than three weeks prior to proof. They can proceed by telephone conference. However, both parties must have at hand parties or principals authorised to provide instructions for settlement. The intention of the conference is to avoid last-minute, door-of-court settlements and the unnecessary expense and inconvenience that may cause.

Experience in ordinary cause personal injury procedure has shown that for this innovation to be successful, the mindset of the parties plays an important part. Conferences are not intended to be mere form-filling exercises. They are intended to facilitate a full and candid exchange of views on all relevant issues, with reference to all available documentation and valuations which by this stage in procedure ought to have been lodged. Although the rules require the conference to take place no later than four weeks prior to the proof diet, there is no reason why it cannot take place at an earlier stage in procedure.

Table of fees

A new table of fees to accompany this new summary cause procedure has been drafted for consideration by the Lord President’s Advisory Committee on Fees, and it is hoped that this will be approved in time for the 1 September commencement date.

The way forward

The Scottish Government has announced the abolition next year of the separate Sheriff Court and Court of Session Rules Councils and the creation of a new Civil Justice Council, one of whose responsibilities will be to oversee the introduction of the reforms recommended in Lord Gill’s civil justice review. One of those objectives, so far as possible, is to achieve consolidation, simplification and uniformity of court rules.

Whatever the future holds, anticipated changes to the privative limit of the Court of Session are likely to herald a significant increase in the volume of personal injury litigation proceeding through the sheriff courts. It will be for the Civil Justice Council in future to consider whether it may be desirable or indeed possible to create one set of rules for all personal injury actions in Scotland. These new summary cause rules represent an attempt to move towards uniformity, within the current framework.

In this issue

- Trapped by the Wildlife Act?

- What constitutes "reasonable endeavours"?

- Reflective learning explained

- Values to the fore

- Employee ownership: removing the barriers

- Reading for pleasure

- Should you be paying your interns?

- Opinion column: John Deighan

- Book reviews

- Council profile

- President's column

- Edinburgh's history unveiled

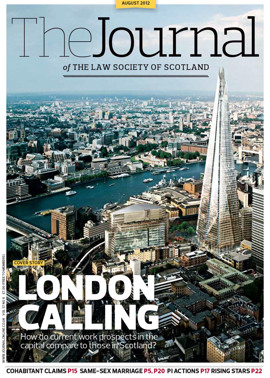

- Capital connection

- Cohabitees and the principle of fairness

- Coulsfield cloned

- A plea in law for equal marriage

- Aiming high: rising stars

- Get your facts right

- Pension rights and TUPE transfers

- 2014: an ET odyssey

- Giving back

- ILG to mark 40 years in style

- Rural lessons for urban conveyancing

- Investing in our own futures

- Training the flexible way

- Business radar

- Code of conduct for MHT work

- Law reform roundup

- The threat from within

- Ask Ash

- The learning curve