Get your facts right

Professional responsibility to the court

The significance of the appeal court decision in Telford v HM Advocate [2012] HCJAC 88 (26 April 2012) lies not so much in the outcome of the appeal but in the court’s observations in respect of a petition to the nobile officium which all the judges regarded as a waste of time, trouble and expense.

The petition arose following the refusal of an application for leave to appeal to the Supreme Court in a case in which the appellant had pleaded guilty to murder, but in spite of that plea, subsequently attempted to appeal to the High Court against his conviction on a number of separate grounds.

Sadly, the petition contained several misstatements of fact, based on a failure to ascertain precisely what had happened at an earlier stage of the case when the case was at appeal in the High Court. In particular, the failure related to how that court had dealt with the various grounds of appeal at the point when the outcome of the appeal was advised, in open court and in the presence of the appellant and his legal advisers.

Among other things, it transpired that there had been no determination of any devolution issue by the High Court and therefore nothing to appeal to the Supreme Court; there had been no attempt to find out directly from the counsel and solicitors who had appeared at the advising as to what was said in court at that point; and there had been no attempt to take a statement from the applicant.

In refusing the petition, the Lord Justice Clerk contented himself by expressing his disappointment that both the petition and the application had been presented in such circumstances. However, in sharing his concerns, Lord Hardie observed that both counsel for the petitioner and those instructing him had failed in their professional responsibility to the court to ensure that cases were presented on an accurate basis. Having set out in some detail why he thought this was so, Lord Hardie concluded that the Scottish Legal Aid Board might wish to consider whether fees and outlays for the events since the High Court advising were a proper charge on the legal aid fund.

Sex offender notification

As well as providing that someone convicted of a listed sexual offence must register as a sex offender for a prescribed or indefinite period according to the offence committed, the Sexual Offences Act 2003 also makes provision in sched 3, para 60 whereby these notification requirements apply where the court determines that there was a “significant sexual aspect” to the offender’s behaviour in committing a non-listed offence. But what does the term “significant” mean?

It was held in Hay v HM Advocate 2012 SCCR 281 that to provide a definition would be futile; that “significance” should be assessed in the light of the purpose of registration being for public protection; that one way of approaching the matter was to consider whether the sexual aspect was important enough to merit attention as indicating an underlying sexual disorder or deviance meriting public protection; and that the sentencer should keep a sense of proportion and use his “common sense”.

Hay was decided along with Thompson v Dunn 2012 SCCR 298 (indecent assault) and a number of other cases in which para 60 was in issue. These cases have now been followed by McGuire v Procurator Fiscal, Glasgow [2012] HCJAC 86 (11 May 2012), where the sheriff considered and applied para 60 to a case of breach of the peace. The police had encountered the accused, who was very drunk and leaning back against a window in a busy public street. His trouser buttons were undone and the police initially thought he was urinating, only to realise that he was in fact masturbating. The sheriff accepted that there was no underlying sexual deviancy in the conduct of the accused and that the catalyst for that conduct was the fact that he was very drunk; but he decided that what had happened was not something which was commonly, or indeed even occasionally, encountered in connection with intoxicated persons in city centre public streets and that accordingly the sexual aspect of the case was “significant”. The High Court refused a bill of suspension against the sheriff’s decision.

Section 259 applications

Section 259 of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 sets out some exceptions to the hearsay rule in criminal cases and has figured in two recent appeals. The problem which arose in Brand v HM Advocate [2011] HCJAC 74 (22 July 2011, but not published on the SCS website until 8 June 2012) was largely one of statutory interpretation.

Suppose A and B are tried together on a charge of assault, acting in concert with each other. At the trial A incriminates B. Can A lead hearsay evidence of an extrajudicial statement by B, in which B says something which is self-incriminatory, but which statement will fall to be treated as inadmissible if the Crown seeks to lead evidence of its having been made?

In Brand, a s 259 application by the first accused seeking authority to lead hearsay evidence of what his co-accused had said to the police was refused by the sheriff, on the basis that since the Crown could not lead that evidence because the circumstances were not Cadder-compliant, to allow it to be led by the first accused would be to admit illegitimate evidence against the second accused (the maker of the self-incriminatory statement), which would inevitably prejudice the latter’s right to a fair trial, something which could not be resolved by directions to the jury. Having considered the common law, case law and legislation in this area, the appeal court agreed with the sheriff and refused an appeal against his decision.

By contrast, in Murphy v HM Advocate [2012] HCJAC 74 (30 May 2012) there was a procedural problem of timing. The s 259 application was late; it was made at a “continued preliminary hearing” and not at a point at least seven days before the preliminary hearing to which the accused had been initially indicted (see s 259(5) and (5A)). The judge dealing with the matter held in the particular circumstances that there was no “cause shown” for its lateness, a decision upheld on appeal.

On the question of timing, the appeal court took the view that the provision allowing for a further preliminary hearing (s 307(1) of the 1995 Act) was in place not to postpone the notice provisions, but to permit the court, at the further diet, to exercise the same powers to dispose of the issue as it had at the initial diet. On the issue of “cause shown”, while there was tension between the requirements of s 259 and s 300A (power to excuse irregularities), ultimately it was a matter of judicial discretion; an appeal court would not interfere unless the use of that discretion was productive of a miscarriage of justice.

Community payback orders

As is becoming apparent, a community payback order is a deliberately flexible non-custodial sentencing option for a criminal court. Among other things, it may include a “conduct requirement” whereby the offender must do or refrain from doing specified things for a prescribed period. But it is now clear from Kirk v Procurator Fiscal, Stirling [2012] HCJAC 96 (15 June 2012) that the offender cannot be required to “refrain from committing a criminal offence” in terms of any such order made.

The point had arisen in a number of cases which were put on hold pending resolution in the appeal court, but it has now been held that, having regard to the language employed in s 227W of the 1995 Act, the Scottish Parliament, in providing for conduct requirements, had done so expressly for the purpose of seeking or promoting the good behaviour of the offender or preventing further offending by him. Any such conduct requirement has to be seen as a means which the court considers necessary to achieve the end of good behaviour on the part of the offender; to impose a requirement to be of good behaviour or to refrain generally from committing criminal offences would be to impose the end as a requirement, not to impose a requirement to seek or promote that end.

The appeal court reached this conclusion on a careful scrutiny of the structure and provenance of the relative legislation, noting that the Scottish Parliament had deliberately departed from the position that obtained in relation to the previous regime of probation orders. Any offending behaviour during the currency of a community payback order would now require to be dealt with simply and separately by the criminal process.

So “roll ups” of summary complaints, at least as far as comprising breaches of probation and new complaints for offences committed while on probation, will presumably pass into history. But not all “roll ups” have that composition.

In this issue

- Trapped by the Wildlife Act?

- What constitutes "reasonable endeavours"?

- Reflective learning explained

- Values to the fore

- Employee ownership: removing the barriers

- Reading for pleasure

- Should you be paying your interns?

- Opinion column: John Deighan

- Book reviews

- Council profile

- President's column

- Edinburgh's history unveiled

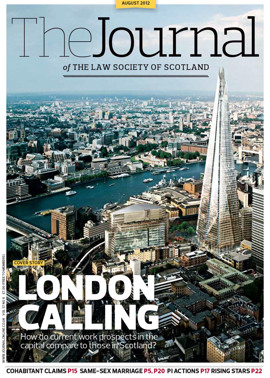

- Capital connection

- Cohabitees and the principle of fairness

- Coulsfield cloned

- A plea in law for equal marriage

- Aiming high: rising stars

- Get your facts right

- Pension rights and TUPE transfers

- 2014: an ET odyssey

- Giving back

- ILG to mark 40 years in style

- Rural lessons for urban conveyancing

- Investing in our own futures

- Training the flexible way

- Business radar

- Code of conduct for MHT work

- Law reform roundup

- The threat from within

- Ask Ash

- The learning curve