Investing in our own futures

Last month’s Journal looked at the challenges resulting from the introduction of alternative business structures in the context of our firms and our businesses. This article will look at what it implies in relation to our professional and individual career development and training. I will advocate the need to revisit the former apprenticeship-type model to ensure the continued provision of high-quality crafted services, and explain how this allows us to position ourselves to respond positively to the new structures and opportunities being created.

Terms such as “master” and “apprentice” may seem dated, but being a master of a professional discipline offers competitive advantage by displaying specialist expertise and the ability to decide what is the “best” solution for a particular client in a particular set of circumstances. It means more than having intellect and analytical skills. Mastery involves having a passion for one’s work; it brings with it a sense of personal satisfaction and the respect of our peers. It also creates a commitment and drive for excellence in the people who work with us.

Setting the scene

The UK profession is living through a period of disruptive change so fundamental that it is difficult to predict what the legal services marketplace will look like five years from now. However, in my view, clients will always need to be able to find good lawyers who can explain and apply complex rules and regulations in order to provide them with practical solutions to their particular problems.

While a lot of the routine work that solicitors used to do has been “commoditised”, in other words, reduced to completing forms and checklists, the more specialist and complicated work will remain in the domain of the legal profession. Every new type of business model that may develop will need lawyers who are skilled at dealing with the law and explaining it to other people. For example, a large legal services department providing 24-hour online access to customers will need to be headed by legal advisers capable of developing systems that enable staff to deal with worried clients and provide them with the right advice. That is not an easy task when coupled with pressures of volume and the need to provide services consistently and commercially. New market entrants that underestimate this complexity may well find themselves on the receiving end of complaints and claims by both clients and shareholders.

Working on the assumption that most of the routine legal work will be siphoned off to organisations that want to “pile them high and sell them cheap”, I would suggest that solicitors’ continued viability rests on focusing on retaining the competitive advantage we have as a result of our specialist knowledge, based on years of training. The recent changes to the undergraduate degree and PEAT 1 (the Diploma) allow Scottish law students to concentrate on doing exactly that. In addition, they are introduced to the need to develop good judgment based on ethical behaviour and the values of the profession. They are exposed to practitioners who tutor them in small groups on specific subjects such as contract and family work. As a result, they can observe these “masters” and consider such questions as “Will I fit in, in this profession?” and “Do I want to become like him or her?”

When they progress to becoming trainees, they need to develop their knowledge and skills in the context of legal practice. Up until as recently as 10 years ago, most of us learned the craft of lawyering by completing many small transactions and processing many routine court matters. This meant that we could learn to practise safely under the direct supervision of a more experienced solicitor, who kept an eye on us and saw what we did well and where we needed more help. We also had the advantage of being able to watch directly what he or she did, providing the chance to ask questions about individual decisions and get direct feedback on our performance as these decisions naturally arose in the course of our daily work. We were gradually given increasing levels of responsibility, of difficulty and client exposure that both the “master” and “apprentice” were comfortable with. However, as firms have become larger and as basic work has become more routinised, there exists less direct exposure to senior people, and limited opportunity for trainees to learn incrementally in this way and develop their professional judgment.

Implications for future training

So what does this mean in relation to how we train our future “masters”? “Communities of practice” are an established mechanism for professional training and development, as they allow a new entrant to observe more senior people in their everyday work, as well as adopt the behaviours and demonstrate the values needed to be accepted as someone that merits time spent in training them.

Etienne Wenger in his book Communities of Practice – learning, meaning and identity (1998, New York: Cambridge University Press) talks about the learning an individual achieves from belonging to such a community, by becoming part of it, by doing that type of work and by the experience gained from working with others within it. However, the cumulative effect of job uncertainty, redundancies, partner defections and economic pressures has been to reduce our “community of practice” and affect people’s willingness to share experience and expertise. Yet, if we are to maintain our competitive advantage by providing high quality legal services, it is essential that we find a way to re-energise our “community” so as to bring in and develop the new “masters” of the future.

Educating lawyers – preparation for the profession of law (Sullivan et al, 2007, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, p22) describes the six tasks of legal education as involving:

- developing the fundamental knowledge and skills students will need;

- providing them with the capacity to engage in complex practice;

- enabling them to learn to make judgments in conditions of uncertainty;

- teaching them how to learn from experience;

- introducing them to the disciplines of creating and participating in a responsible and effective professional community; and

- forming them as able and willing to join an enterprise of public service.

Accepting that achieving all of this cannot be the sole responsibility of one part of the educational chain, we need to ensure that we individually play our part in this process so that students become trainees, trainees become qualified, and experts and senior people pass down their expertise.

Personal training and development

In addition to the obligation on the profession as a whole to support the training and development of new entrants, there are a number of implications for us as individuals as our career options become more diversified and less linear, as alternative options become available. We will be faced with reduced job certainty and more choices. We may decide to work in-house; we may prefer private practice; we may want to work in litigation; we may choose another jurisdiction.

Given the impact on our health and wellbeing from doing the type of work we enjoy, we need to be clear about why we decided on law as our profession and what motivates us. It is important to achieve a sense of personal satisfaction by doing a job that has meaning and purpose and that employs all of our knowledge, skills and abilities.

As a result, we need to target areas for personal development and training that build on what we are good at and what enables us to retain our unique expertise. We need to be proud of being solicitors who care about our clients and our profession.

In addition, regardless of how senior we are, we need to stay familiar with new technology, as some of the new devices and software will save us time and make us more effective. Those of us who are “masters” must be prepared to spend our time and energy helping and inspiring younger people, as we represent what the profession stands for and, as a result, are role models that other people follow in relation to our behaviour and attitudes. Finally, new entrants must feel that they have made the correct career choice for them and have a commitment to become a lawyer, with all that implies in relation to helping clients resolve disputes, providing access to justice, and representing the rights of the individual in relation to dealings with others and the state.

Commercial imperative

In my view, it is not an exaggeration to say that the identity of the UK legal profession is under threat. The increasing “commoditisation” of routine work, coupled with the introduction of alternative business structures, risks dissipating our ability to develop the future “masters” of our profession. We need to invest in the new entrants who aspire to deliver our values, who have a calling to be lawyers who help people, and who want the personal satisfaction of doing a job that has meaning and purpose.

This is not solely an aspiration goal – it is also commercial reality. To survive as practising solicitors, we must maintain our ability to provide complex and specialist services in a way that clients want and value. This requires us to invest in training and developing ourselves and our trainees.

In this issue

- Trapped by the Wildlife Act?

- What constitutes "reasonable endeavours"?

- Reflective learning explained

- Values to the fore

- Employee ownership: removing the barriers

- Reading for pleasure

- Should you be paying your interns?

- Opinion column: John Deighan

- Book reviews

- Council profile

- President's column

- Edinburgh's history unveiled

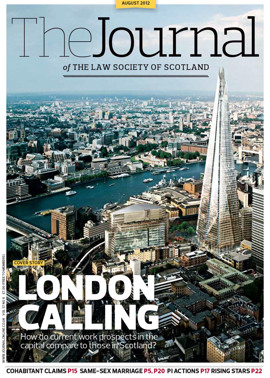

- Capital connection

- Cohabitees and the principle of fairness

- Coulsfield cloned

- A plea in law for equal marriage

- Aiming high: rising stars

- Get your facts right

- Pension rights and TUPE transfers

- 2014: an ET odyssey

- Giving back

- ILG to mark 40 years in style

- Rural lessons for urban conveyancing

- Investing in our own futures

- Training the flexible way

- Business radar

- Code of conduct for MHT work

- Law reform roundup

- The threat from within

- Ask Ash

- The learning curve