Opinion column: John Deighan

On 6 July 1535 Thomas More stepped on to the gallows and serenely placed his head on the block at which he was duly decapitated. It was the use of law to rewrite reality that Thomas More could not condone. King Henry VIII refused to be content with More’s silence on the King’s adulterous marriage to Anne Boleyn and instead determined to force a public approval from his former Chancellor.

In their willingness to give their lives for a principle, men like Thomas More witness to the importance of that principle. His testimony to the inviolability of conscience points to the importance of not abandoning it. The full consequences of More’s lesson have been learned throughout history, and our modern human rights framework is built on the premise that there are principles that lie beyond the grasp of kings, presidents and political assemblies, recognising that conscience places an ultimate responsibility on each person to do what they reason to be right.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights permitted the promotion of common rights around the world. In Europe it prompted the creation of legal processes to hold governments to account for securing those rights for their citizens. Those rights are now perilously close to being hollowed out and shown to be worthless in the face of demands for radical autonomy. Alexander Solzhenitsyn famously warned the West of the threat to its survival when he identified that in our society, “destructive and irresponsible freedom has been granted boundless space”.

If human rights exist at all, they must be based on something firmer than the good dispositions of those who wish to uphold them. The preferences and wishes of individual people, and even societies, fluctuate throughout time and place. A dependence on these for legal rights places those rights at the mercy of trends and fashions which are easily manipulated.

For all the benefits of our free society, it is as subject to the rise and fall of particular fashions as any other. In fact, the use of the media to form particular values and modes of behaviour has proven to be considerable. Celebrity culture places people with particular talents for singing, acting or just for being physically attractive, in positions as social leaders and role models with influence that often dwarfs that of many elected politicians.

It is in such a context that we come to the issue of same-sex marriage. Whether we agree or disagree with their aims, efforts to change the public perception of homosexual relationships have been considerable. Marshall Kirk and Hunter Madsen are perhaps the most coherent in asserting the aims of their efforts in this regard. (There is no room to explore the understanding of homosexuality in this short article, but sadly there has been much distortion of the view held by those who propose a particular understanding of human sexuality which ties it inextricably with its biological significance for procreation. Proposing such a value in no way suggests malice for those who do not accept that understanding. Yet some same-sex marriage campaigners have made this a perpetual part of their rhetoric.)

That such significant legal changes have occurred in such a short period of time shows the effectiveness of the culture in leading politics and the law. It is of little surprise that it creates the context where a call for same-sex marriage should win an essay prize for identifying the most-needed new legislation in our country.

Such a step, however, invites the state to be the basis for determining the value and worth of private relationships. Marriage has always been of public interest in all societies, however primitive or advanced, because of the plain reality that sexual relationships produce children.

It is the simple reason why it is that type of relationship that had a privileged status, until the advent of radical freedom had individuals demand that they should get the same recognition despite not being in the same type of relationship. Much endeavour has been put in to rationalising why a change must be made; but these attempts are, to varying degrees, attempts to rationalise away common sense and universal human experience.

It is a line of thought which demands a new conformity on all people and which has been accurately described as a dictatorship or relativism. Like supporters of football teams, some have embraced the new cause with unthinking loyalty and will not be deterred from their path.

It is ironic that our human rights instruments recognise marriage as a relationship between a man and woman, yet human rights is used as a basis for demanding the change. That would be a triumph of arbitrary power over the objective reasonableness of justice.

In this issue

- Trapped by the Wildlife Act?

- What constitutes "reasonable endeavours"?

- Reflective learning explained

- Values to the fore

- Employee ownership: removing the barriers

- Reading for pleasure

- Should you be paying your interns?

- Opinion column: John Deighan

- Book reviews

- Council profile

- President's column

- Edinburgh's history unveiled

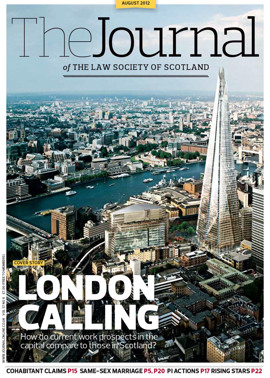

- Capital connection

- Cohabitees and the principle of fairness

- Coulsfield cloned

- A plea in law for equal marriage

- Aiming high: rising stars

- Get your facts right

- Pension rights and TUPE transfers

- 2014: an ET odyssey

- Giving back

- ILG to mark 40 years in style

- Rural lessons for urban conveyancing

- Investing in our own futures

- Training the flexible way

- Business radar

- Code of conduct for MHT work

- Law reform roundup

- The threat from within

- Ask Ash

- The learning curve