Rural lessons for urban conveyancing

The drill is well known. Conveyancers must check that a seller has good and marketable title, but for many years that has not been the end of the matter. An ever increasing number of eclectic matters such as statutory notices, the contaminated land regime and s 75 agreements must be smoothed over, lest you be left with a disgruntled client seeking to hold their agent to account for any inherited problems.

The Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003 (“the 2003 Act”) brought another trap for the unwary, introducing the Register of Community Interests in Land as yet another staging post to be called on in the journey to completion. A check on this register, administered by the Keeper of the Registers of Scotland, is necessary to ensure that no community bodies have registered a pre-emptive right to buy. By s 40 of the Act, a registered community interest in land allows that community to jump above any other buyer in the pecking order of transferees.

It is true that the risk of that particular trap can be overstated. It is clearly not a huge concern for the lawyer acting for the purchaser of a flat in the centre of Edinburgh, although the writer can anecdotally confirm the sighting of a private search firm’s rather unnecessary confirmation several years ago that neither a community nor an agricultural tenant held pre-emptions over just such an area (in the latter case, under the Agricultural Holdings (Scotland) Act 2003).

That said, some outwardly urban (or at least suburban) areas can turn out to be surprisingly rural, thus taking land in places like Neilston within the ambit of registrable land in terms of s 33 of the 2003 Act and the related statutory instrument SSI 2009/207 (as evidenced by the activated interest numbered CB00034: the relevant population threshold is 10,000 people).

Empowering communities?

Beyond that quirk, is there anything for “urban” practitioners to worry about? Not yet, but there might be soon. The Scottish Government is consulting on ideas for a proposed Community Empowerment and Renewal Bill. That sentence is a direct lift from the biography of the Twitter account @CommEmpower, but non-tweeting consultees can respond online and by post per the resources at www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2012/06/7786/0.

The consultation document does not contain draft legislation. That is to follow in a further consultation in summer 2013. Admittedly, this may make consultation responses a little woollier at this stage than might be the norm, but there is much to consider. The Scottish Government’s Consultation on the proposed Community Empowerment and Renewal Bill, opened on 6 June 2012, sets out a commitment for more community planning (i.e. planning carried out with the active participation of the local community), and the related goals of unlocking enterprising community development and renewing Scotland’s communities. Should, for example, community councils have a greater role? Is Scotland’s rather dated allotment legislation fit for purpose?

That might not seem overly radical, but the consultation suggests there might be a power for communities to gain access (temporarily or on a forced sale basis) to unused or underused resources. Fans of the controversial BBC Scotland documentary The Scheme might recall the challenges some Kilmarnock residents faced when they sought to (re)invigorate their community by taking control of a public building that had fallen out of use. Another proposal suggests that an urban right to buy could be introduced, perhaps modelled on the 2003 Act scheme where a community body must first be incorporated, then register an interest in a suitable register and await its coming on to the market.

The right and the reality

Focusing for the moment on the potential to transplant the ready-made rural right-to-buy regime to urban areas, mutatis mutandis, while this may seem attractive it has to be considered that only 11 communities in Scotland have actually registered and then activated a community interest in land since the legislation came into force. A timely study by the Scottish Government’s Rural Analytical Unit (Overview of Evidence on Land Reform in Scotland (2012), at www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2012/07/3328) details the various reasons why the 142 entries to the Register of Community Interests in Land (with another two pending at the moment) may not have eventually led to a transfer to the community, even if Scottish Ministers initially approved the transfer.

Such reasons include a lack of funds, or the landowner simply backing out of the sale. Even the communities who received that ministerial rubber stamp managed to get further than residents of Holmehill and Kinghorn, who were denied access to the right to buy because of, respectively, a failure to meet the strict “late registration” public interest test in s 39 of the 2003 Act (where there was a perception that the community was trying to thwart the planning process), and a failure to comply with the mapping requirements of the legislation (see the author’s “No place like Holme: community expectations and the right to buy” (2007) 11 EdinLR 109, and “Access to Land and to Landownership” (2010) 14 EdinLR 106).

While there may be some inspiration sought from the 2003 Act, it may be that the foutery framework is not an inspirational model after all. One might also question the logic of modelling an urban right to buy on a system that is, according to a Scottish Government press release, about to be subjected to a “radical” review (“Radical rethink on land reform under way”, at www.scotland.gov.uk/News/Releases/2012/07/Land-Reform24072012).

Amber alert

In the aftermath of the successful challenge to s 72 of the Agricultural Holdings (Scotland) Act 2003 in Salvesen v Riddell [2012] CSIH 26 March 2012; under appeal to the Supreme Court), the Scottish Parliament will have to be more careful than ever to chart the path between a landowner’s interests in maintaining a property as derelict (whatever that might be defined to mean) or as a land bank, as against the interests of the wider community to use such property. There is no reason to suppose parliamentary draftsmen will not do just that, so what does this mean for practitioners?

A resounding “watch this space”. The initial consultation is open to responses until 26 September. As noted, a second consultation will follow. Fans and opponents will thus have ample opportunity to make representations as to what form the legislation should take, but it seems fair to surmise that legislation of some sort will follow, thus creating yet another consideration for conveyancers and their clients.

In this issue

- Trapped by the Wildlife Act?

- What constitutes "reasonable endeavours"?

- Reflective learning explained

- Values to the fore

- Employee ownership: removing the barriers

- Reading for pleasure

- Should you be paying your interns?

- Opinion column: John Deighan

- Book reviews

- Council profile

- President's column

- Edinburgh's history unveiled

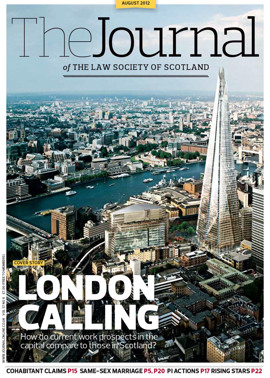

- Capital connection

- Cohabitees and the principle of fairness

- Coulsfield cloned

- A plea in law for equal marriage

- Aiming high: rising stars

- Get your facts right

- Pension rights and TUPE transfers

- 2014: an ET odyssey

- Giving back

- ILG to mark 40 years in style

- Rural lessons for urban conveyancing

- Investing in our own futures

- Training the flexible way

- Business radar

- Code of conduct for MHT work

- Law reform roundup

- The threat from within

- Ask Ash

- The learning curve