Should you be paying your interns?

In the last year we have seen a sharp increase in the number of internships, which seem to be yet another symptom of the current economic conditions. For many graduates facing unprecedented competition for jobs, an internship may be the only way to gain valuable work experience.

One of the main issues arising from this upsurge in the use of interns is the confusion over the right to be paid. Last year the Scottish Government introduced an “adopt an intern” scheme by providing funding to employers to enable them to pay their interns. According to recent figures 193 placements have already been offered, with 66% of the interns obtaining a permanent role at the end of their internship.

What is an intern?

An internship is a loose term and does not have a standard legal definition. According to the Best Practice Code for High Quality Internships, an internship is “where an individual works so as to gain relevant professional experience before embarking on a career. Well managed, high quality internships should be beneficial to both employer and intern”.

Within the Scottish legal profession, the use of summer students is commonplace and such placements would obviously come under this definition. At Dundas & Wilson we offer summer students six-week paid placements which form part of our traineeship recruitment exercise.

Should interns be paid?

The main problem is that many internships are unpaid or offered on an “expenses only” basis. According to research by the CIPD in 2010, 37% of interns were not paid. (This figure covers a cross section of industry rather than relating to the legal sector.) More recent figures published in July 2012 from the Higher Education Statistics Agency, show that in the last year there was a 23% increase in graduates (equating to over 6,200 graduates) who are working for free, either as volunteers or as interns.

Yet these interns are often working standard 9am-5pm hours and carry out the same range of responsibilities as paid employees. The problem of course is compounded by the fact that interns who are desperate to get work are the least likely to challenge a refusal to pay them, for fear of scuppering their future chances in the labour market. It seems that many employers and interns are unaware of their rights in this area.

The legal position

Legally, if an intern fulfils the definition of a “worker”, they should be paid the national minimum wage (NMW). In addition as a worker they should also accrue statutory holiday entitlement for the period of their placement.

Under s 230 of the Employment Rights Act 1996, a worker is someone who has entered into “any other contract, whether express or implied and (if it is express) whether oral or in writing, whereby the individual undertakes to do or perform personally any work or services for another party to the contract whose status is not by virtue of the contract that of a client or customer of any profession or business undertaking carried on by the individual”.

In essence, therefore, the legal definition of a worker covers a broad range of working relationships, from casual workers to bank staff, where an individual agrees to a contract for personal service which has mutual obligations. So if an intern is expected to come into work every day, perform tasks and comply with instructions, there is every likelihood that they are a worker. In contrast individuals who merely work shadow are not likely to fall within the NMW legislation, since these individuals only observe and are not performing work.

Although there is an exception in the NMW Regulations that student work experience placements of less than one year are exempt from the NMW, the exemption only applies if the work experience is part of the student’s course. It does not therefore cover the situation where a third or fourth year law student works in a law firm over the summer in the hope of getting a traineeship.

Are they volunteers?

Genuine volunteers, on the other hand, have no right to be paid, and sometimes the legal position relating to their status can be confused with interns. There is a raft of case law concerning the legal status of volunteers which, apart from one case (Murray v Newham CAB UKWEAT/1096/99), has consistently distinguished volunteers from workers. As such they are not workers who are protected from anti-discrimination legislation or eligible to receive holidays. According to an article in the Guardian from last year, some employers are actually advertising internship-type positions as a “voluntary” role to get round this legal issue.

The NMW Regulations contain a specific exemption for “voluntary workers” if they work for a charity, voluntary organisation, associated fundraising body or statutory body. Outwith these sectors, an individual can still volunteer to work for a commercial organisation but would not fall under the specific NMW exemption. If they were wrongly labelled as a volunteer they could still be entitled to be paid the NMW. Ultimately in the event of a dispute the matter would have to be resolved by an employment tribunal.

Legal challenges

We are only aware of two cases where unpaid interns have challenged the failure to pay wages for an internship-type role. In both cases the claimants were successful.

In Vetta v London Dreams Motion Pictures Ltd (ET/2703377/08) the respondents had engaged a self-employed production designer (Ms Wyatt) who, in turn, took on the claimant as an intern on an “expenses-only” basis to work as her assistant. The expenses were paid by the respondent. The claimant argued she was not a volunteer like many, but rather a worker due to the nature of the work which she carried out and the fact that this was not any form of training programme. The tribunal agreed that she was indeed a worker and therefore entitled to the NMW plus any accrued holiday she had not taken.

Last year the NUJ issued a press release referring to a tribunal case which they had supported. An unpaid intern Kerri Hudson won her claim against TPG Web Publishing Ltd after she spent weeks working for the My Village website carrying out a variety of tasks. Despite working every day and eventually being put in charge of recruiting other interns, and being in charge of a team of writers, the company did not pay her because she was an intern. The tribunal ordered payment of wages calculated at NMW rates and accrued holiday pay.

Recent developments

In 2009 the Panel on Fair Access to the Professions, a body of experts chaired by Allan Milburn, was tasked with reviewing improvements in equal opportunities and social mobility. One section of the final report criticised the internship process as not being sufficiently transparent. Positions were often gained according to parental connections rather than on merit, and graduates from poorer backgrounds were not able to afford spending several months as an unpaid intern. Concerns were also raised that a significant proportion of internships did not provide high quality work experience.

In response to the final report, the Gateways to the Professions Collaborative Forum was formed which is an ad hoc advisory body which works alongside DBIS to remove barriers to professional careers. (The Law Society of England & Wales is a signatory.) In July 2011 they published a Common Best Practice Code for High Quality Internships. The Best Practice Code does not have legal force and is really just a statement of good practice, but makes it very clear that internships should be paid and provides guidance on recruitment, treatment and supervision.

More recently, in September 2011 the Westminster Government published NMW Guidance for employers on work experience, internships and placements, specifically including advice on when an individual is entitled to be paid the NMW. This user friendly guidance contains a number of case studies to explain who is and is not a worker.

There has also been some indication that HMRC, which has responsibility for enforcing the NMW, is taking an active interest in sectors where there is a high level of unpaid internships. Failure to pay the NMW to an intern can result in more than an employment tribunal making an award of back pay. There are also criminal penalties if there has been a wilful neglect to pay the NMW.

For any organisation that does still offer unpaid internships or summer placements, it is perhaps time to review the NMW Guidance and consider whether there may be a legal obligation to pay their interns. It's not simply legal issues that should prompt action in this area. With the growth in intern websites aimed at exposing employers such as Interns Anonymous, there are also reputational and PR issues to be considered.

In this issue

- Trapped by the Wildlife Act?

- What constitutes "reasonable endeavours"?

- Reflective learning explained

- Values to the fore

- Employee ownership: removing the barriers

- Reading for pleasure

- Should you be paying your interns?

- Opinion column: John Deighan

- Book reviews

- Council profile

- President's column

- Edinburgh's history unveiled

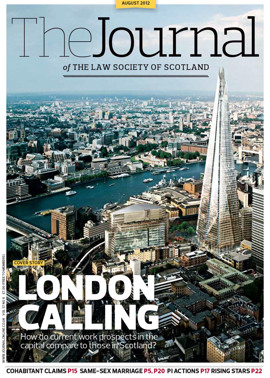

- Capital connection

- Cohabitees and the principle of fairness

- Coulsfield cloned

- A plea in law for equal marriage

- Aiming high: rising stars

- Get your facts right

- Pension rights and TUPE transfers

- 2014: an ET odyssey

- Giving back

- ILG to mark 40 years in style

- Rural lessons for urban conveyancing

- Investing in our own futures

- Training the flexible way

- Business radar

- Code of conduct for MHT work

- Law reform roundup

- The threat from within

- Ask Ash

- The learning curve