Trapped by the Wildlife Act?

A new offence introduced under the Scottish Parliament’s Wildlife and Natural Environment (Scotland) Act 2011 came into force with effect from 1 January 2012. It introduces vicarious liability in relation to the mistreatment of wild birds.

The offence is directed towards landowners. The maximum penalty on summary conviction is six months’ imprisonment or a fine on level 5 of the standard scale (£5,000), or both.

Landowners need to be aware of implications of this legislation, and will need to plan carefully in response. Doing nothing is not an option, and neither is a token response. But the good news is that the statute does not expect the impossible of landowners, and there are statutory defences against vicarious liability.

As history has shown, the efficacy of such defences is dependent on proper planning and procedures, and training and communications, with ongoing monitoring and fine tuning. The utility of the documents trail cannot be overstated. In the face of possible criminal prosecution, half-hearted and token efforts cannot cut the mustard.

Background

Wildlife campaigners have long noted and speculated on the extent of illegal raptor persecution in Scotland – “persecution” consisting of activities including the disturbance of nests, stealing of eggs, poisoning, setting of traps and others. The informative and interesting website www.raptorpersecutionscotland.wordpress.com, which names names and shows pictures, records numbers and details of incidents dating from 1989 in which a common factor is the discovery of a dead bird of prey in mysterious circumstances on or near the boundary of a shooting estate in rural Scotland.

Often, no one knows how the bird has died or who is responsible for the killing, and it is reasonable to speculate that many more raptors die than are discovered in these remote areas.

Even Scottish Field, the magazine catering for outdoor sports enthusiasts, accepts as obvious the implication that the birds are being killed “to protect grouse and other game stocks”. Game is being preserved and managed for the estates’ sporting businesses, to ensure there are sufficient birds for their paying tenants and/or guests to kill. The new offence allows prosecutions against the estate owner or factor where an employee or tenant commits an offence against a raptor, as a deterrent to “those owners and managers who turn a blind eye to questionable practices on their land”.

The legislation

In an amendment to the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, which deals with the prohibition of “certain methods of killing or taking wild animals”, the 2011 Act, s 24 inserts new ss 18A and 18B. In relation to any land, “where… a person (A) commits a relevant offence while acting as an employee or agent of a person (B) who– (a) has a legal right to kill or take a wild bird on or over that land; or (b) manages or controls the exercise of any such right... B is also guilty of the offence and liable to be proceeded against and punished accordingly”.

Proceedings may be taken against B whether or not proceedings are taken against A.

“Relevant offence” is defined in s 18A(6), in which references are made to earlier sections of the Act dealing with:

- protection of wild birds, nests and eggs;

- prohibition of certain methods of killing or taking wild birds;

- the possession of pesticides; and

- attempts to commit such offices.

Commentary

Vicarious liability for a criminal offence is not a new concept. Jones & Christie, Criminal Law (4th ed), 397 point out that a prosecution for criminal liability usually involves the accused both having committed the crime (actus reus) and having the intention to commit the crime or the knowledge of it having been committed (mens rea). The concept of vicarious liability supersedes the common law requirement for both action and intent to be present when one person can be held responsible for the acts of another. It is thus “unknown in the common law of crime [but]... is, however frequently imposed by statute”.

Vicarious liability extends liability to both A and B, but the statutory provision allows for B to be prosecuted irrespective of whether A is prosecuted. Perhaps A has disappeared or is otherwise unavailable for prosecution, but again, the real reason for concentrating on B must be to catch landowner offenders, and the subsidiary deterrent effect of the threat of prosecution dissuading them from turning a blind eye to any acts committed by their employees.

Any attempts by landowners to evade vicarious liability by making their employees self-employed are struck at by the Act, which also covers the case where person A is carrying out relevant services for person B, and is not just an employee.

Section 18A of the 1981 Act, as amended, does give the landowner a statutory defence:

“(3) In any proceedings under subsection (2), it is a defence for B to show– (a) that B did not know that the offence was being committed by A; and (b) that B took all reasonable steps and exercised all due diligence to prevent the offence being committed.”

Much has been written about the steps that must be taken by responsible landowners by way of risk assessments, training for employees regarding relevant offences, defining clear areas of responsibility, maintaining a pesticide register and supervising pesticide use, amongst other suggestions. Particularly useful in this area is the Scottish Lands and Estates’ “Due diligence good practice guide”, which can be found on their website. This guide contains detailed suggestions of reasonable steps that can be taken by a landowner, and also indentifies who might be potentially vicariously liable. This is brought into focus when dealing with the example of a large grouse moor which may have shooting tenants, managing agents, and a head gamekeeper.

It is to be noted that the legislation refers to person B taking “all” reasonable steps and exercising “all” due diligence. This would be by actively and regularly checking that the systems in place are being adhered to, and that the systems instituted remain of a sufficient nature in the specific circumstances. The test of what is reasonable is an objective one, and the question of whether all reasonable steps have been taken is a matter of fact and degree.

It has been suggested that the question of whether all reasonable steps have been taken is “is in practice a difficult hurdle to overcome”, and until there is some case law from which we can extrapolate the likely views of a court, it is difficult to establish what “all” might mean in the particular context of the provisions in the 2011 Act.

The “due diligence defence” appears in other statutes creating vicarious liability criminal offences such as, for example, the Licensing (Scotland) Act 2005, which provides that the holder of a premises licence can be held vicariously liable for the actions of his/her employee or agent. Again the licence holder must not have known the offence was being committed and must have exercised all due diligence to prevent it taking place.

But perhaps the landowner may have other defences in terms of the common law if they are able to prove that, under s 18A of the 1981 Act, person A is not “acting as” their employee or agent. In an employee/employer relationship the employer is likely to have more control over their employee than a landlord might have over their tenant, and may therefore be more likely to be found vicariously liable for the actions of that employee. Furthermore, the employee must be acting within the course of his/her employment and not for his own benefit. The Stair Memorial Encyclopaedia suggests the courts have indicated that an employer’s instructions must be very specific to result in any breach not leading to a claim against the employer in terms of vicarious liability.

The wording of s 18B provides that vicarious liability applies where “A is providing relevant services for... B”. This seems to be a question of fact and difficult to challenge in the same way that it is possible to question whether A is acting as B’s employee.

All caught

Scottish Lands and Estates’ “Due diligence good practice guide” rightly takes the introduction of the 2011 Act seriously, and identifies real issues for landowners. Put simply, the idea of a law abiding landowner doing nothing is not an option when that landowner can be prosecuted for the actions of their employee or agent. The legislation applies not only to an owner of a large sporting estate but also to an owner of a small farm. It is crucial for every landowner to take a proactive role in the management of their land.

In this issue

- Trapped by the Wildlife Act?

- What constitutes "reasonable endeavours"?

- Reflective learning explained

- Values to the fore

- Employee ownership: removing the barriers

- Reading for pleasure

- Should you be paying your interns?

- Opinion column: John Deighan

- Book reviews

- Council profile

- President's column

- Edinburgh's history unveiled

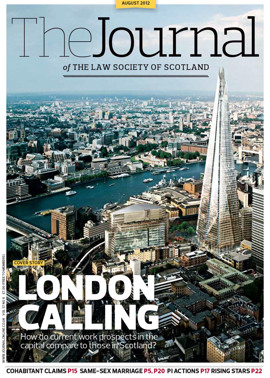

- Capital connection

- Cohabitees and the principle of fairness

- Coulsfield cloned

- A plea in law for equal marriage

- Aiming high: rising stars

- Get your facts right

- Pension rights and TUPE transfers

- 2014: an ET odyssey

- Giving back

- ILG to mark 40 years in style

- Rural lessons for urban conveyancing

- Investing in our own futures

- Training the flexible way

- Business radar

- Code of conduct for MHT work

- Law reform roundup

- The threat from within

- Ask Ash

- The learning curve