What constitutes "reasonable endeavours"?

The recently decided appeal in EDI Central Ltd v National Car Parks Ltd [2012] CSIH 6 (20 Janary 2012), affirming [2010] CSOH 141, provides further judicial guidance on the interpretation of an obligation to use reasonable endeavours. While an obligation to use reasonable endeavours is self-evidently general and vague in nature, it is, nevertheless, a term much used in commercial contracts.

The case concerned a proposed development of the Castle Terrace car park in Edinburgh. NCP agreed to transfer their interest in the car park to a developer, EDI, who were bound to pursue a development of the site “with all reasonable endeavours and as would be expected of a normal prudent commercial developer”, and also to act in good faith in achieving the development objective. NCP were to share in the development profit.

However, when it became apparent that the development would not proceed, NCP contested EDI’s attempt to implement the provisions for unwinding the agreement (by transferring their interest in the car park back to NCP and repayment of an initial premium), on the basis that EDI had not discharged their reasonable endeavours obligation. NCP were unsuccessful in this.

Test of performance

The first area of interest arising from the case is the court’s specific pointers as to the interpretation of “all reasonable endeavours”. The following can be extracted from the relevant judgments in the Outer and Inner House:

- The obligation to use “all reasonable endeavours” is a more onerous obligation than one simply to use “reasonable endeavours”.

- “It is difficult to conceive that an obligation to use ‘best endeavours’ requires a party to take steps which are

unreasonable”. The implication here is that “best endeavours” is not a higher obligation than “all reasonable endeavours”.

The party on whom the obligation is placed will be expected to explore all avenues reasonably open to him and to explore them all to the extent reasonable. But unless the contract otherwise stipulates, he is not required to act against his own commercial interests”.

If one necessary hurdle cannot be overcome, “all reasonable endeavours” does not require the obligant to waste his time seeking to overcome other problems.

It was suggested that the obligant is required to inform the other party of difficulties and to discuss solutions. However, this was not an absolute requirement but one subject to the circumstances of the case.

The obligant must genuinely do their best to achieve the desired result and not merely go through the motions.

As a separate matter, in the context of the obligation to act in good faith it will be of interest to note the statement (by the Lord Ordinary) that “It is, of course, no part of Scots law that, in the absence of agreement, parties to a contract should act in good faith in carrying out their obligations to each other.”

Practising what it preached?

Notwithstanding this guidance, a “reasonable endeavours” obligation remains inherently imprecise, so it is interesting to see how the court applied the above to the actual circumstances of the case.

In the NCP case, the development failed due to the absence of provision for alternative car parking. The court accepted that there was only one feasible site for that alternative provision. Both that site (and the Castle Terrace site) were owned by Edinburgh Council. On the basis of the evidence, the court found that there was no prospect of the council making the alternative site available to be developed as parking.

While it was accepted that EDI had adopted a light and informal touch in their negotiations with the council, the court appeared to look at the underlying reality of the situation and found on the evidence that, as the development could not proceed without alternative provision and the only appropriate alternative site would not be made available by the council, there was no point in the matter being pursued.

So rather than consider whether the developer had tried as hard as it reasonably could, the court looked at the underlying factual reality and decided that as any further effort would be futile, the developer had discharged its obligation.

On the face of it, it might be said that the court did not adhere to the guidelines it had itself set out.

On the one hand it is indicated that the obligant must genuinely do their best and explore all reasonable avenues, yet in relation to the actual case the court decided a light touch was good enough when the evidence pointed to the fact that, whatever level of endeavour was expended, the result would be the same.

One can understand NCP’s frustration with this outcome: even in difficult cases a combination of diplomatic pressing and skilful negotiation can yield a solution not immediately apparent. Should an obligation to use all reasonable endeavours not mean that one doesn’t just take an initial no as the final answer?

It is interesting to speculate as to what NCP envisaged “reasonable endeavours” would extend to when it entered the agreement. It seems inconceivable that the assessment made in court (i.e., that the development was entirely dependent upon the council making a specific site available for parking) had not been made by the parties before concluding the agreement, yet NCP must have thought an “all reasonable endeavours” obligation would be sufficient to overcome this particular hurdle.

Flesh it out

It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that this was another commercial relationship which took on a different character following the financial downturn of 2007. In 2005 when the deal was struck, property development was in good health and presumably NCP reckoned that from a practical perspective the financial incentive to EDI of a successful development would be far more effective than precise contractual obligations.

Of course, with the economic downturn of 2007-08, appetite for development waned and so no doubt did the developer’s hunger to pursue the proposal.

If there is a lesson to be learned from this fact-specific decision, it is that if “reasonable endeavours” is simply a convenient formula to avoid consideration of precise requirements, in the expectation that the commercial interests of the parties will secure the desired outcome, one should have regard to the potential for a change in the financial drivers. If sufficiently critical, it is always open to put meat on the bones of “reasonable endeavours” by stipulating the minimum actual steps which would require to be taken to secure the relevant objective.

In this issue

- Trapped by the Wildlife Act?

- What constitutes "reasonable endeavours"?

- Reflective learning explained

- Values to the fore

- Employee ownership: removing the barriers

- Reading for pleasure

- Should you be paying your interns?

- Opinion column: John Deighan

- Book reviews

- Council profile

- President's column

- Edinburgh's history unveiled

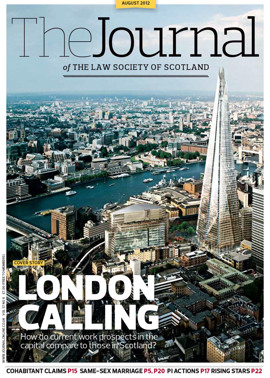

- Capital connection

- Cohabitees and the principle of fairness

- Coulsfield cloned

- A plea in law for equal marriage

- Aiming high: rising stars

- Get your facts right

- Pension rights and TUPE transfers

- 2014: an ET odyssey

- Giving back

- ILG to mark 40 years in style

- Rural lessons for urban conveyancing

- Investing in our own futures

- Training the flexible way

- Business radar

- Code of conduct for MHT work

- Law reform roundup

- The threat from within

- Ask Ash

- The learning curve