Independence before the law

“Generating more heat than light” is a terrible cliché when applied to political debate. It is perhaps used most frequently by fussy lawyers (do I repeat myself?) lamenting the imprecision with which politicians discuss legal issues about which we think we know a great deal. Like most clichés, however, it became a cliché because it is so often both true and useful. And it could with much justification be applied to the debate so far on the legal issues surrounding Scottish independence.

To some extent that is because the debate puts lawyers in an unusual position, in that we can identify many questions, yet provide few answers. This creates a feedback loop in which lawyers raise questions for politicians who, keen to have the law on their side, punt the questions on to other lawyers.

The referendum

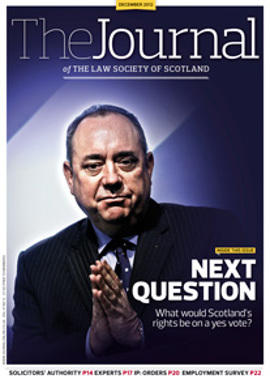

The first such question raced out of the traps almost as soon as the Prime Minister unexpectedly kickstarted the debate back in January: does the Scottish Parliament have the power to legislate for an independence referendum without permission from Westminster? Alex Salmond said “aye”; David Cameron said “naw” (I quote from memory), and much argument ensued.

The only way conclusively to resolve that argument would be for the Scottish Parliament to legislate and for the courts to deal with the inevitable challenge. One of the few areas of unanimity was that that would be a sub-optimal outcome.

While legal argument no doubt contributed to each side’s negotiating position, it is ultimately political agreement that has ridden to the rescue. So, on this at least, let there be light.

On 15 October 2012, Messrs Salmond and Cameron signed an agreement providing for the Scottish Parliament to legislate for an independence referendum, by way of a “section 30 order” (i.e. an Order in Council made under s 30 of the Scotland Act 1998), to be made in early 2013, on three conditions:

The draft order also provides for election broadcasts and mailshots (which are otherwise outside the Scottish Parliament’s competence) to be governed by the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000.

So the UK Government got its way on the “single question” issue – neither “devo max” nor “devo plus” will feature. But the Scottish Government seems to have got its way on the other disputed points: timing (probably October 2014); franchise (the Scottish Parliament and local government electoral roll – which includes EU citizens – will be used, and the voting age limit can be lowered if the Parliament wants); and the wording of the question (to be reviewed by the Electoral Commission but ultimately for the Parliament to set). The rules on campaign finance, oversight and conduct of the referendum will also be set by the Scottish Parliament.

There are already rumblings of controversy over the Scottish Government’s preferred question and proposed campaign finance rules, but the Order should at least remove any further legal controversy. The lawyers can therefore take a back seat on those issues. However, to paraphrase Churchill, this is not the end of the debate, nor even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning, in that the focus can now turn from the process to the issues. In other words, back to the heat.

Starting from where?

The most heated question right now is whether an independent Scotland automatically would be a member of the EU, or would leave the EU on independence and have to apply for membership. The Scottish Government insists it would be the former, while the UK Government believes it would be the latter. Others have offered their tuppenceworth – the European Commission President Jose Manuel Barosso has said that if part of a member state becomes independent from that member state it would also leave the EU, and a Commission spokesman made similar comments when asked about the possibility of Catalonian independence (though he back-pedalled swiftly when pressed on whether his comments applied to Scotland).

There is, however, one point that seems fairly clear – if there is the will to do so, an independent Scotland would (on some set of terms and sooner or later) be an EU member. Scotland is part of an EU member state, and so meets the conditions of EU membership (QED). Questions arise, however, because the EU is not an organisation that anyone can join as long as they meet certain conditions. Like a nightclub bouncer, the EU reserves the right to refuse entry and to set the terms on which entry will be allowed. So, what’s the EU equivalent of “no trainers”?

Countries joining the EU through the accession procedures do not generally get Treaty opt-outs such as those the UK enjoys (principally from the euro, but also from the Schengen free movement area and various other areas of co-operation).

Succession to the opt-outs?

A Schengen opt-out for an independent Scotland would perhaps be uncontroversial, given that the UK and Ireland are already outside and it would serve no great interest to re-erect Hadrian’s Wall.

However, the UK’s euro opt-out is a well-known source of tension with at least some Eurozone member states, particularly given our resulting refusal to participate in the EU’s various “stability” (i.e. bailout) mechanisms. The euro’s difficulties do not seem to be denting the enthusiasm for monetary union among key member state governments, and so it seems unlikely that they would allow an accession candidate country to opt out of euro membership.

That might be seen as a lack of faith in the euro as a political project, and so could further jeopardise its real-world viability. Certainly Croatia was given no choice on euro membership in its recent accession negotiations, and Estonia adopted the euro in December 2010 notwithstanding the currency’s then-obvious problems (a move described in certain quarters of the British press as like boarding the Titanic after it hit the iceberg).

The euro issue is perhaps the main reason why the Scottish Government is insisting so strongly that an independent Scotland would automatically be a member of the EU, on the UK’s existing terms. If that was correct, other member states’ views would not matter – Scotland could simply insist on membership on the same terms as the UK.

Unfortunately for the Scottish Government’s position, there is no direct precedent in favour of that conclusion, as there has never before been a situation in which part of an EU member state became independent from that state yet sought to remain within the EU.

In wider international law, it is usually the case that when a minority part of a state becomes independent it assumes a brand new identity, without retaining the original state’s treaty rights and obligations (for example, Pakistan was a “new” state following the partition of India, as were all the former Soviet states bar Russia following the breakup of the USSR).

Diluted voice

Another difficulty is that the EU’s internal organisation depends on the number of member states. When a new member is added, it is entitled to a Commissioner, and a judge on each of the General Court and Court of Justice. Accession also changes the distribution of the European Parliament, with existing states losing MEPs. Adding a new member state therefore dilutes the existing states’ representation within each of the EU institutions. This is one of the key reasons why all accessions require a Treaty change approved by every existing member state.

Ultimately, the key problem is that there is no obvious mechanism by which an independent Scotland could insist on EU membership over the objections of other member states. We lawyers can speculate to our hearts’ content on the “correct” legal position, but if the existing member states did not want Scotland to achieve or inherit EU membership on independence, then it is most unlikely that we could force the issue. It is by no means clear that the Court of Justice of the European Union would have jurisdiction to decide the matter, but even if it did, the court is as much a political institution as a legal one. It may therefore be unlikely to overrule any member state objections on such a politically sensitive point.

The legal issue would therefore be likely to boil down to a political and diplomatic solution, and in particular whether Scotland could persuade all the other member states to agree to membership contemporaneously with independence and/or on the UK’s existing terms, or would have to accept some less attractive arrangement. Unfortunately for the prospects of an enlightened debate, it is very unlikely that member states would want to discuss such issues while the prospect of independence is still hypothetical (though Spain has recently taken a harder line against the notion of automatic Scottish membership as the Catalonian independence movement has grown). We are therefore likely to go into the referendum with this key issue still shrouded in murk.

Parting the waves

The other key issue that has recently attracted attention is the split of North Sea oil and gas revenues, and in particular the division of the UK’s North Sea Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) recently reported on the likely fiscal position of an independent Scotland. It concluded that a “geographic” split of North Sea oil would leave an independent Scotland in more or less the same position as at present, though more vulnerable to the volatility of North Sea oil revenues, while a “population-based” division of the revenues (i.e. Scotland getting about one-10th of revenues) would require some difficult spending choices to be made. Any assessments of a “geographic” division must, however, depend largely on the location of the boundary. Unfortunately for the purposes of the debate, that is again an issue that could only be conclusively decided in inter-governmental negotiations in the event of a “yes” vote.

No doubt the Scottish Government would want the boundary drawn as far south as possible, and so may argue to retain the boundary used in the Civil Jurisdiction (Offshore Activities) Order 1987 (which runs almost directly east from Berwick, and establishes the boundary of Scottish jurisdiction over offshore platforms). A vast majority of the UK’s oil and gas production would be within that zone.

The UK Government, by contrast, would presumably want to retain as much of the current UK zone as it could. It might use as a starting point the principle of equidistance (i.e. if a point in the North Sea is closer to the Scottish coast than the English then it would be in the Scottish zone, and vice versa), which would put a smaller majority of North Sea oil production (and an even smaller majority of gas production) within the Scottish zone.

This approach was used in 1999, over SNP objections, to set the limits of the Scottish Parliament’s power to regulate fisheries. This is the line the IFS used in its report.

While international boundaries are often set using the equidistance principle, that is not set in stone (neither figuratively nor, obviously, literally). Any division of the UK EEZ would therefore depend at least as much on political negotiation as on legal analysis, and in particular would probably form part of a much wider discussion on the division of UK assets and liabilities.

So what’s left for the lawyers?

While it is true that many of the key issues would have to be decided politically rather than legally, that does not mean there is no contribution lawyers can make. Clients will need advice on these issues over the next two years, perhaps to assist them in contributing to the debate or perhaps just because the issues affect their business. Lawyers providing that advice will need to understand not just the legal issues but also how Scotland actually works – how its institutions, businesses and systems of governance all fit together. Constitutional and administrative law, as with other areas of practice, has to work in the real world – or what else is it for?

So, even if we cannot give definitive answers, we can suggest what the most likely outcomes are and advise on measures to mitigate any issues clients see as risks. And, happily for those keen on playing a part in the debate, there is no sign that the politicians will be any less keen on finding legal arguments they can adopt in service of their cause.

In this issue

- Barriers to sibling contact

- Legal rights, second families and siblingship

- "I'm a chicklet and I live in a hatchery"

- And our survey says...

- No overtaking?

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion column: Martin Morrow

- Book reviews

- Council profile

- President's column

- 2012: new starts, and challenges

- Independence before the law

- Who do you think they are?

- The expert approach

- Is all publicity good publicity?

- Turning point?

- Young and guilty

- Doubly secure

- Forced marriage: an update

- New age, new image

- A security loophole

- Quit while you're ahead

- When threats are enough

- Practice ground

- Mergers: keeping people onside

- Law reform roundup

- PI Guidelines: new edition

- Ask Ash

- Business radar