Mergers: keeping people onside

Mergers between law firms continue to make news, and it is highly likely that this trend, which has accelerated sharply since the onset of the economic downturn, will continue for the foreseeable future. While every circumstance will be distinctive, and the reasons for the mergers will vary to some extent, financial considerations will tend to dominate and be one of the key drivers for the strategy.

However, the establishing of the new working environment within the merged firm will be a critical factor in determining the success or otherwise of the merger. The human cost of careless restructuring can be high, and morale – always fragile at a time of organisational change – can take a great deal of time to recover, if at all.

Those in the public sector have been used to regular restructuring, whether as a result of local government reorganisation (such as that of 1996) or, more recently, as part of ongoing and regular budget cuts. In the private sector, mergers have only become common relatively recently. How firms have coped with such change, especially the human side, will soon become known and talked – or tweeted – about. It is therefore in the interests of firms agreeing to merge, to think carefully about the impact this will have on those who will work in the firm post-merger.

Swallowed up?

Inevitably, the HR process tends to concentrate on contractual matters. What are the staff paid; what are their terms and conditions of employment as regards holidays, overtime, annual salary reviews and the like? Important as these features are, they certainly are not the whole story.

The level of morale will of course be affected by tangible items such as holidays and salaries, but what often makes a real difference – apart from the success or otherwise of the organisation concerned – is the way staff perceive they are valued, how they are communicated with, how decisions that affect them are taken, and how they feel their jobs and careers are being considered.

In thinking what to do about such issues, a lot will of course depend on the circumstances of the merger. Are the two firms merging of roughly equivalent size, or is one in effect taking over the other? History would tell us that the latter circumstance is the more usual, and so it is likely that the staff in the larger firm will feel more secure and “in control” compared with those working for the smaller unit.

Where people will sit should be one of the prime considerations for the planning process, as the way people then work and relate to each other will help shape the ethos of the merged firm. Looking at the history of mergers, some have sought to preserve the identity of the smaller firm by, for example, having significant groups of the staff from that firm sit together when they move to the larger firm, so they

do not feel anonymous or isolated. In general, I do not believe it is sensible to segregate the staff in this way, as it will create a false division between those engaged in similar types of work, and it will tend to emphasise rather than minimise differences.

Planned approach

If, when the decision is made to merge, mechanisms are put in place specifically to plan for the HR implications of the merger, there will be far greater chance of potential issues being raised and planned for, thus providing the newly merged firm with a head start in dealing with potential difficulties or differences between the two sets of individuals working there. This will typically be led by the HR professionals in both firms, but there is also much to be said for involving others where practical.

If there are staff consultative bodies, it is useful to involve the members of these, and on occasion external assistance can be sought. Some have espoused a formal survey of both sets of staff pre-merger, but there are dangers in this, as no guarantee can be made on responding positively to expressed concerns at what is likely to be a pressured and highly charged period.

Perhaps the best approach is to adopt an HR plan for the merger and its aftermath. The plan will contain different elements according to circumstance, and the relative sizes of the organisations involved, but the principles will be similar, especially the need to anticipate and plan for areas of difficulty.

What, then, should be contained within such a plan? The starting point is probably the inevitable comparisons between key working conditions, already referred to. This will involve the collection of data on staff and a look at the differences between the two firms. Does one firm have a flexitime scheme, albeit perhaps not contractual? Does one firm award additional days of annual leave after so many years of service? How are the annual public leave days allocated? What is the policy on paying for exams and for study leave? Does either firm award benefits such as child nursery vouchers? What are the relative arrangements for any pensions? It then has to be worked out what contractual arrangements fall within the TUPE (transfer of undertakings) legislation.

Feeling heard

Once the basics of terms and conditions comparisons have taken place and decisions have been made as to how the differences can be resolved, the next stage is to look at current HR issues in both firms. It is rare indeed for there to be no such issues, and any HR professional will tell you that managing such issues is largely a case of judgment as to when to be proactive and when to let things take their course for a period of time. An advantage of any merger is that any issues that have been left can perhaps be given a nudge in the right direction, using the merger as the raison d’être.

It’s also worth noting that what appear to be small or insignificant details can cause disproportionate upset or fuss. As an example, it is likely there will be a small number of smokers in each firm – if in one firm such staff are not permitted to have smoke breaks but in the other firm such breaks are the norm, one can see that making a decision on this, and ensuring it is communicated properly, will be important – trivial as the issue might appear.

Another step that might be useful and help staff be part of the decision making process is to set up a short term consultative group containing staff from both firms (perhaps in the proportion of total staff from each firm). If there are existing consultative forums, it may be politic to use at least some of the representatives from these, but alternatively some consultation could take place, perhaps ensuring that those selected or elected are representative of different areas of the firms, or are a mix of fee earning and support staff.

If such a forum is set up, make sure that it has defined terms of reference, and that it works within tight parameters and deadlines so that it can be a positive force for change rather than an inhibitor. If handled correctly it will start the process of staff working together and, hopefully, understanding each other’s points of view. Some thought should also be given to who might chair it – possibly someone from the larger firm who is not directly involved in managing or resolving HR issues, so that he or she is seen as reasonably neutral. This might mean the chair not being someone from HR, although as with any such group, time may be an issue. Ideally this group would continue to meet until a (short) period of time after the merger has been achieved, so that its members can see through some of the changes.

Continuing goodwill

Finally, one of the HR-related issues that can be overlooked in the pressured environment of a merger is being alert to those key staff who may be unsettled by the change but who will not necessarily come forward to share their concerns. Staff who are regarded as important to the success of the new merged firm should be communicated with regularly and informally, so that they feel valued and so that any legitimate concerns they have can be identified. Of course, some such staff will rightly see a merger as an opportunity for them to shine, but especially for the smaller firm, key staff may worry that their career ambitions may be subsumed and less known than they have been in their own firm. Partners and senior management will find that being proactive in seeking out concerns and talking them through will yield significant dividends when the merger occurs, and in the often difficult ensuing months.

Dealing successfully with the “people” side of a merger will be a major achievement, given that many of these aspects of a business are intangible and, unlike the figures on a balance sheet, less obvious to spot. Starting the merged firm with issues identified and resolved, and with staff seeing that such issues have indeed been managed, will help ensure that the merger begins with goodwill from those whose efforts can make it a success.

In this issue

- Barriers to sibling contact

- Legal rights, second families and siblingship

- "I'm a chicklet and I live in a hatchery"

- And our survey says...

- No overtaking?

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion column: Martin Morrow

- Book reviews

- Council profile

- President's column

- 2012: new starts, and challenges

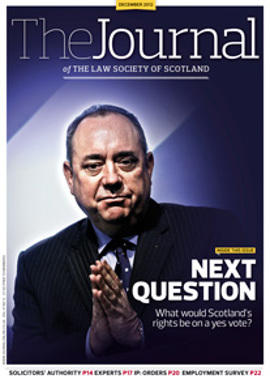

- Independence before the law

- Who do you think they are?

- The expert approach

- Is all publicity good publicity?

- Turning point?

- Young and guilty

- Doubly secure

- Forced marriage: an update

- New age, new image

- A security loophole

- Quit while you're ahead

- When threats are enough

- Practice ground

- Mergers: keeping people onside

- Law reform roundup

- PI Guidelines: new edition

- Ask Ash

- Business radar