New age, new image

Sport and traditional media have always been intertwined. Now, new media are revolutionising how people communicate and how sport projects its own image, with Twitter at the forefront.

The profiles of stars such as Jessica Ennis, Dan Carter and Usain Bolt have increased through accessibility to a global audience. Fans follow their idols to learn more about them and “tweet” directly to them, in the hope of a reply. Sponsors are beginning to measure the value of endorsement deals based on followers and online image.

Trouble in 140 characters

Through messages of 140 characters or fewer, tweeters can publish and communicate instantaneously. Over 500 million active users make 340 million tweets and over 1.6 billion search queries per day. In sport, footballer Cristiano Ronaldo leads the field, with over 12 million followers. As a platform for online discussion Twitter excels: during the 2011 FIFA Women’s World Cup Final, 7,196 tweets were sent per second about the match between Japan and USA.

Recently a growing number of sportspeople have discovered that tweeting can lead to trouble, if they let their guard down. Twitter’s beauty is also its beast – the immediacy of publication and a global platform means inappropriate content can cause instant trouble. Use of Twitter is regulated in sport in three primary ways: the athlete contract, participation agreements and endorsement agreements.

Regarding participation, Paraskevi Papahristou, the Greek triple jumper, was sent home from London 2012 for a disparaging tweet in breach of IOC social media guidelines. At the Rugby World Cup 2011 Samoan Eliota Fuimaono-Sapolu was censured, having criticised the scheduling of matches as comparable to the Holocaust. The basis for action by the tournament organisers was clear; on contractual principles there was a breach of the rules of participation. No defence was available.

Some sports, particularly the American professional sports, prohibit, police and punish tweets during live action, using rules that each athlete subscribes to. Tariff fines of $7,500 or more are regularly issued, for tweets that are not offensive, nor in disrepute, and possibly not even written by the athletes themselves.

Commercial partners too have been seen to react swiftly to their endorsee’s repudiatory misbehaviour. Trouble befell Australian swimmer Stephanie Rice, who celebrated the Australian rugby side’s defeat of South Africa in 2011 with an ill-advised homophobic blurt. No apology could stop Jaguar Australia immediately cancelling their sponsorship agreement and requisitioning the new car Rice had enjoyed since the outset of the relationship, costing Rice over AUS$100,000.

What of human rights?

Arguments regarding human rights are unlikely to succeed for sportspeople who covet attention through Twitter. “Private life” includes social interaction and the right to develop relationships, even at work (Niemietz v Germany (1992) 16 EHRR 97). Covert filming of travelling to work along a public street does not exclude the right to privacy (see McGowan v Scottish Water EATS/0007/04), and the right to privacy when engaging in sado-masochistic activities in a club, subsequently published online, is not lost (Pay v United Kingdom [2009] IRLR 139). On each occasion, however, while rights were engaged, they were not infringed where the action was proportionate. Therefore, in reacting to Pay’s conduct through dismissal, Pay’s employer acted proportionately having regard to Pay’s role as probation officer.

Sports governing bodies, tournament organisers and clubs are all engaging in training, adopting social media policies, and monitoring to ensure that an acceptable public image is maintained. Monitoring will generally be permissible and not in breach of either ECHR or data protection principles, provided that information collated is not retained longer than necessary. Sport is also becoming au fait with practical steps such as insisting on the removal of offending material once a problem is identified. Disciplinary action needs to be pursued with care, in particular in framing charges against tweeters. Should a racist tweet be regarded as a breach of a code on social media, a breach of equalities, or both with one aggravating the other?

While it is sometimes said that sportspeople are less accessible to and more disconnected from the public than ever before, a new line of intimacy through social media is developing. Sport is well placed to regulate, leaving tweeters to ensure that they do as sports stars have always been encouraged to do – present a positive public image at all times, or face consequences.

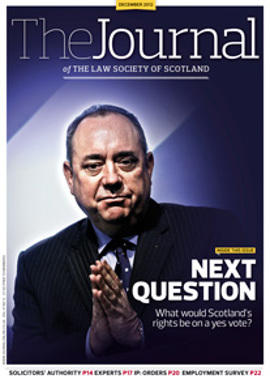

In this issue

- Barriers to sibling contact

- Legal rights, second families and siblingship

- "I'm a chicklet and I live in a hatchery"

- And our survey says...

- No overtaking?

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion column: Martin Morrow

- Book reviews

- Council profile

- President's column

- 2012: new starts, and challenges

- Independence before the law

- Who do you think they are?

- The expert approach

- Is all publicity good publicity?

- Turning point?

- Young and guilty

- Doubly secure

- Forced marriage: an update

- New age, new image

- A security loophole

- Quit while you're ahead

- When threats are enough

- Practice ground

- Mergers: keeping people onside

- Law reform roundup

- PI Guidelines: new edition

- Ask Ash

- Business radar