Opinion column: Martin Morrow

Criminal court solicitors are facing up to the prospect that clients who can contribute to the cost of their defence will shortly require to do so.

SLAB and the Government have decided the contribution is to be collected by the solicitor from their client. This is despite the fact that SLAB has considerably greater resources than any practitioner and is already committed to collecting contributions in solemn criminal and in civil legal aid matters. It is interesting to note that SLAB’s recovery rate in civil cases is about 40%, which is not dissimilar to the court’s recovery rate of unpaid fines. Research suggests that with financial penalties under diversion from prosecution, the recovery rate is about 29%. There is no reason to think that the solicitor will achieve a better rate. If the solicitor does not make 100% recovery, clearly any losses translate as effectively a pay cut for the solicitor and their practice in these difficult times.

To add insult to injury, the Government has advised that if solicitors withdraw from acting for clients who do not meet contributions, the PDSO stands ready to represent that former client, in order to preserve the existing trial diet. There is no mention of the PDSO requiring to collect the contribution. The irony, of course, is that an accused who is due to make a contribution but elects not to, will effectively be provided with legal aid without making a contribution. This seems a contradiction in terms and one wonders if the Government has thought about this.

It is my suspicion that it has. The Government will have worked out that it does not have anything like the resources to provide a PDSO solicitor in every summary trial court across Scotland, standing ready to represent unrepresented accused. I have no doubt that it has decided that the solicitor will for various reasons continue to act for the client who does not pay a contribution. It will, I estimate, have decided that, first, the criminal court solicitor will not wish to see his client base diluted by losing the client. Secondly, it is not financially viable to withdraw from acting where the contribution is comparatively small. If the client’s contribution is £85 it is probable, so the Government thinks, that the solicitor will act for the fixed fee (£485) minus the contribution (£85): a net fee of £400. The alternative is to lose the client to the PDSO and be paid 50% of the net fee, i.e. £200.

If the Government’s analysis is correct, the client who should be paying a contribution will then receive legal aid from their existing solicitor without requiring to fund it. As can be seen from the foregoing, this is a win-win situation for the defaulting client and a lose-lose situation for the solicitor.

There is very little solicitors can do about this. They could ask a sheriff to adjourn a trial to allow a client to meet the contribution. The sheriff, however, is not concerned with how a solicitor is paid. Anyway, the administration of justice cannot be held to ransom by an accused simply not paying his contribution. The sheriff is concerned with vulnerable witnesses, not vulnerable solicitors.

In truth, the only help may come from the Law Society of Scotland. Maybe the Society could be persuaded to formalise a practice rule providing that no solicitor may conduct a trial for any accused person who, having been assessed as required to contribute towards the cost of their legal aid, fails to do so in full, before the trial commences.

This has the attraction that the principle espoused by the Government is supported by the Society. Moreover, if an unrepresented accused does not meet their contribution, the solicitor withdrawing from acting will still receive 100% of the net fee. This is because nobody else is acting and there is, therefore, no transfer of legal aid. The Government also makes a saving. For every client who does not pay their contribution, SLAB pays the solicitor the net fee rather than the fixed fee.

Any legal aid savings may be only a drop in the ocean compared with the cost and delay caused by unrepresented accused. These persons do not know the law; they have no idea of procedure; their capacity to try and lead inadmissible evidence knows no bounds. The sheriff will require to explain the procedure to them, and there will be no mechanism for agreeing uncontroversial evidence. Moreover, who does the procurator fiscal negotiate with in the course of the trial? All the cases due to follow that of the unrepresented accused will also be held up.

The overall effect will be to increase the expense of criminal court proceedings. I have no doubt that the Government has been advised of this, but to expect it to take the advice to heart is beyond praying for.

In this issue

- Barriers to sibling contact

- Legal rights, second families and siblingship

- "I'm a chicklet and I live in a hatchery"

- And our survey says...

- No overtaking?

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion column: Martin Morrow

- Book reviews

- Council profile

- President's column

- 2012: new starts, and challenges

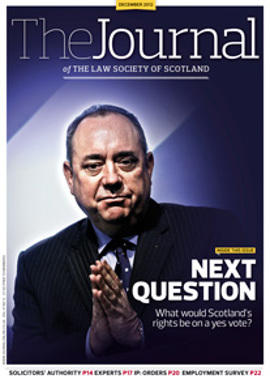

- Independence before the law

- Who do you think they are?

- The expert approach

- Is all publicity good publicity?

- Turning point?

- Young and guilty

- Doubly secure

- Forced marriage: an update

- New age, new image

- A security loophole

- Quit while you're ahead

- When threats are enough

- Practice ground

- Mergers: keeping people onside

- Law reform roundup

- PI Guidelines: new edition

- Ask Ash

- Business radar