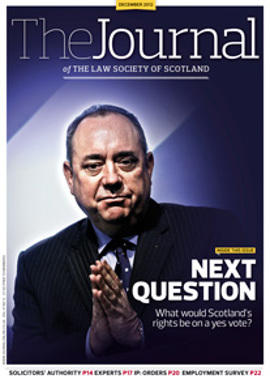

Who do you think they are?

On 5 September 2012, the Inner House issued its opinion in the linked cases of Cheshire Mortgage Corporation Ltd v Longmuir & Co’s Judicial Factor, and Blemain Finance Ltd v Balfour + Manson LLP [2012] CSIH 66, upholding the opinion, delivered after a proof before answer, of Lord Glennie which granted absolvitor in favour of each defender: [2011] CSOH 157.

It is considered that the opinion of the Inner House is of significance to solicitors not only in Scotland but also throughout the United Kingdom. The decision is also important in that it is indicative of the preparedness of the Law Society of Scotland Master Policy insurers to litigate to a conclusion matters of significant principle that affect the profession at large.

The pursuers in both actions operated as residential property lenders under the umbrella of the Blemain Group (“the lenders”). Two further actions by other lenders within the group against other firms of solicitors were sisted pending the outcome of these decisions.

Classic fraud

The facts were relatively straightforward. In late 2004, borrowers approached the defenders, advising that they were the owners of unsecured properties upon the security of which they wished to raise funds for the purchase of other properties abroad. The borrowers advised the defenders that they had already negotiated loans from the lenders, that the defenders would only be acting on behalf of the borrowers, and that the lenders were instructing their own solicitors with regard to putting in place the lenders’ standard securities.

The lenders had already, either directly or through intermediaries, carried out their own identification checks in respect of the borrowers. The loan transactions followed a normal course, with the defenders corresponding with the lenders’ appointed solicitors. At the time of the drawdown of the loans, the borrowers instructed the defenders, in terms of formal written mandates, to remit their loan funds to third parties in connection with the intended acquisition of the properties abroad.

Shortly after the loan transactions concluded, it came to the attention of the lenders that their borrowers had carried out identity theft of the true owners of the properties in question, that mortgage frauds had been perpetrated, and the lenders required to discharge the standard securities that they held on the basis that these had not been granted by the true proprietors. The lenders were left with only personal rights of recovery against the individuals who had carried out the identity thefts, which remedies were, of course, worthless.

A narrow case

In seeking to recover their losses, the lenders chose not to pursue any remedy against the solicitors whom they had instructed to act on their behalf in the putting in place of their standard securities, but rather chose to pursue a remedy against the borrowers’ solicitors, that is the defenders.

The lenders were not able to pursue the defenders in breach of contract, as clearly there was no contract between the lenders and the defenders. They did not seek to pursue a remedy against the defenders in negligence, it being questionable as to whether, in the circumstances, the defenders owed any duty of care to the lenders especially in circumstances where the lenders had instructed their own solicitors, or even whether, if such a duty was owed, that duty had been breached. Rather the lenders sought to pursue a remedy against the defenders under the principle of breach of warranty of authority, essentially arguing that the defenders had warranted that they acted on behalf of the “true” individuals of the names given by the borrowers, and had essentially warranted that their clients (the borrowers) were the true proprietors of the properties against which the loans were being advanced.

In presenting their case, the lenders sought, to a very considerable extent, to rely on the English case of Penn v Bristol & West Building Society [1997] 1 WLR 1356, a decision of the Court of Appeal, and then the leading authority on the principle of breach of warranty of authority. Lord Clarke, who issued the opinion of the Inner House, sought to distinguish Penn from the facts in Cheshire and Blemain, in that in Penn it was clear that the solicitors in question were acting on behalf of both a husband and wife in circumstances where it was clear that at no time had the wife instructed the solicitors to represent her interests in the transaction in question. In Cheshire and Blemain, there was no dubiety that the defenders had instructions to act on behalf of both the husband and wife borrowers. Lord Clarke preferred the arguments and analysis set out by Judge Hegarty QC in the English case of Excel Securities v Masood [2010] Lloyds Rep PN 165, the facts in which were remarkably similar to those in Cheshire and Blemain.

Essentially, the Inner House held that: “All that the agent [the defenders] is warranting is that he has a client and that client has given him authority to act. It would be quite unreasonable and inappropriate to extend this to an implied warranty that his client has a certain attribute or attributes”. The Inner House has effectively held that in the ordinary course of transactions, solicitors do not warrant or guarantee the identity of their clients.

No guarantees

It is considered that the opinion of the Inner House is one that is both sound on the facts and reflects commercial reality. Had the court found in favour of the lenders, it would mean that in all transactions solicitors would be warranting or guaranteeing the identity of their clients to third parties.

The implications of such for the profession at large, and for the Master Policy insurers, would be enormous. No matter what steps any solicitor undertakes to “identify” their clients properly, one cannot exclude the possibility in this day and age of the solicitor being provided by that client with forged identity documentation. Certainly in ensuring that new clients provide photographic identification, one seeks to limit the possibility of a client being other than who they purport to be, but one cannot rule out altogether the possibility of a solicitor being provided with a forged passport, or forged photographic driving licence, or indeed any other form of forged identification documentation.

Risk management issues

It is always easy to look at sets of facts and circumstances retrospectively and comment that if this, or that, had been done, such a claim might have been avoided. Hindsight is a wonderful thing! In both the Cheshire and Blemain cases, the solicitors in question had not acted for the borrowers at the time of their respective purchases of the properties over which the standard securities were to be granted.

As has been alluded to in previous Journal articles on the question of fraud, one should perhaps ask: “Why am I, a solicitor in Glasgow, being instructed by clients (for whom I have not previously acted) who live in Edinburgh in respect of a property in Edinburgh? Why are they not instructing the solicitor who acted for them at the time when they bought? Why are they not using other Edinburgh solicitors? Why are the clients not in a position to provide the title deeds? Why am I being asked to correspond with the clients at an address other than that to which the property transaction relates?”

Asking such questions could (not necessarily will) disclose that a transaction is not all that it purports to be. Nowadays, knowing your client involves more than simply checking that you have carried out the necessary identification checks. It involves a proper understanding of why you have been instructed and the ultimate purpose underlying the transaction.

Finally, in both the Cheshire and Blemain cases the solicitors received instructions towards the end of the transaction to mandate the loan funds received to third parties. As soon as funds have washed through a solicitor’s clients’ account, they become “clean” money. It is recommended that only in the clearest of circumstances, where both the client and the intended third party recipient of funds are particularly well known to the solicitor, should any solicitor agree to implement a mandate directing payment of funds passing through their clients’ account to a third party.

Further, in letters of engagement or terms of business letters, solicitors should expressly decline to accept mandates to pass on clients’ monies to a third party, especially in circumstances where so doing would be an unusual part of the overall transaction. (Remitting the whole or part of the proceeds of sale of a residential property transaction to a lender to redeem a mortgage would, of course, be excluded from the foregoing principle.) If a client wants to pass on monies to a third party, leave it to the client to do so from their own account. To quote the Master Policy insurers’ mantra: “Do not let a client’s problem become your problem!”

Remember these?

For further commentary on fraud and the possible steps to avoid it, see, for example, “Frauds and scams beware” (Journal, March 2011, 42); “Legal risks: a conference reviewed” (Journal, July 2011, 44); “The many faces of mortgage fraud” (Journal, November 2011, online exclusive); and “Chinks in your defences?” (Journal, April 2012, 38).

In this issue

- Barriers to sibling contact

- Legal rights, second families and siblingship

- "I'm a chicklet and I live in a hatchery"

- And our survey says...

- No overtaking?

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion column: Martin Morrow

- Book reviews

- Council profile

- President's column

- 2012: new starts, and challenges

- Independence before the law

- Who do you think they are?

- The expert approach

- Is all publicity good publicity?

- Turning point?

- Young and guilty

- Doubly secure

- Forced marriage: an update

- New age, new image

- A security loophole

- Quit while you're ahead

- When threats are enough

- Practice ground

- Mergers: keeping people onside

- Law reform roundup

- PI Guidelines: new edition

- Ask Ash

- Business radar