Young and guilty

Youth crime and sentencing

It is well established that the youth of an offender may constitute a mitigating factor when it comes to the matter of sentence, but there is of course no hard and fast rule. Two recent (but very different) cases make this point.

In Roy v HM Advocate [2012] HCJAC 134 (29 August 2012), the appellant had been convicted after trial of a particularly brutal murder committed when he was just under 18. The victim was a year younger; both were still at school. The trial judge fixed the punishment part at 18 years, a disposal challenged on appeal on the basis (in part at least) that insufficient consideration had been given to the age of the accused, and the punishment part should be fixed on the basis that there might be hope of rehabilitation and reform over a period of time.

This submission was somewhat undermined by the fact that the appellant was a mature and intelligent young man from a good background and was not the subject of any addictions. Having reviewed HM Advocate v Boyle [2009] HCJAC 89, Hibbard v HM Advocate [2010] HCJAC 111, and Mitchell v HM Advocate [2011] HCJAC 10, the court declined to interfere with the approach of the trial judge and refused the appeal.

By contrast, the problem which arose in Greig v HM Advocate [2012] HCJAC 127 (5 October 2012) was the level of sentence to be imposed on an adult aged 52 for repeated sexual offences committed in 1974 and 1975 when he was aged 14 and 15. The victims were two young female relatives then aged between six and eight years and the crimes occurred at times when he was acting as their babysitter. As well as using lewd practices towards each child, he had assaulted and raped each of them. The trial judge imposed a sentence of eight years’ imprisonment, regarding the offences as having occurred when the accused was in a position of trust.

The appeal court characterised this latter comment as inappropriate, and set out what it regarded as the correct principles to be employed in sentencing an adult offender for crimes committed when a child. First, it rejected the submission that the sentence in such cases should be the same (in terms of the period of time in custody) as would have been imposed on him had he still been a child; both the sentencing and custodial regimes were quite different in that regard. Next, the court rejected any idea that the level of sentence should be that which would be imposed for the offence, had it been committed by an adult on a child; a significant factor in assessing culpability was the age of an offender. Finally, the sentence had to take into account the offender’s age and relative immaturity at the time of the offence, along with his conduct since then: in the present case, 37 years had elapsed since the date of the offences, during which time the appellant had never been convicted of anything. The trial judge had failed to place adequate weight on these factors, so the sentence was reduced to five years.

Football bannng orders

Section 51 of the Police, Public Order and Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 2006 provides the statutory basis for a sentencing option which is becoming increasingly used in Scotland against those often described as “football hooligans”. But the section needs careful scrutiny, for not all forms of criminal behaviour with a football connotation fall into the category of a “football-related offence”, as defined in the Act, and which potentially would give rise to the imposition of a football banning order (FBO).

Such was the situation in MacDonald v Procurator Fiscal, Glasgow [2012] HCJAC 133 (26 October 2012) where, shortly after Rangers had gone into administration and the chief executive of Celtic (Peter Lawwell) had made certain comments about the situation, the accused had placed a message on Twitter stating “Lawwell needs a bullet. Simples”. He ultimately pleaded guilty to breach of the peace by sending a message of a threatening and offensive nature to a social media site; but as well as being made the subject of a community payback order, he received a three-year FBO.

On appeal, he accepted that his behaviour was “football-related”, but not that it related to a “football match”: see ss 51(4)(b), 51(6)(c) and 55 of the 2006 Act. Further, even if the message was partly related to a football match, it did not constitute conduct relating to a specific football match and there were no grounds to believe that a FBO would help to prevent violence or disorder “at or in connection with a football match”.

Although the Crown argued that s 51 was broad enough to cover the present circumstances (even though the Twitter message made no mention at all of any match), the appeal against the FBO was upheld. There had to be some link between the behaviour and a football match “played or intended to be played”; nor could it be said that what the appellant had done was motivated “wholly or partly” by such a match. In the circumstances, the imposition of a FBO was incompetent.

Delays in the appeal court again

In my last column, I noted the delays in the completion of the appeal in Toal v HM Advocate [2012] HCJAC 123, where (for a variety of reasons) seven years elapsed between the start and the end of the process. Now a delayed appeal case has ended up in Strasbourg, attracting national publicity. On 6 November 2012 the European Court of Human Rights found the UK to be in breach of the reasonable time guarantee under article 6(1) of the Convention and awarded “just satisfaction” of €6,000 to the appellant in Beggs v United Kingdom (Application no 25133/06), ECHR 406(2012).

To rehearse all the opinions delivered in the Scottish courts at the many varied stages of Beggs’s case would fill many columns of the Journal, but suffice it to say that his appeal against his conviction in 2001 for a murder committed in 1999 was finally concluded on 9 March 2010 (Beggs v HM Advocate 2010 SCCR 681). In an opinion running to 128 pages, the appeal court dealt with the many grounds of appeal then outstanding as a result of the steps taken both pre-trial and at the trial itself. The application for leave to appeal had been lodged on 17 October 2001, something of which the appeal court was acutely aware since part of its opinion contained a full account of all the procedural steps taken prior to the final appeal hearing. This was the area which was revisited in Strasbourg, resulting in another long opinion.

The European Court calculated the total period of delay in the appeal court as 10 years, 3 months and 21 days, holding however that a substantial proportion of that period had been caused by the appellant’s own conduct. In doing so, the court carefully broke into discrete sections the various parts of the whole period, rejecting in many instances the appellant’s claims that the appeal court (and consequently the UK) had caused the breach of article 6(1). But it also identified periods of inactivity where the Scottish court had failed to take steps to progress matters of its own motion.

Of course, the conduct of the state authorities and the appellant himself were only two of the factors to be taken into account when assessing the reasonableness of the length of the proceedings in the light of the whole circumstances. The court had no difficulty agreeing that the other two factors (the complexity of the case and what was at stake for the appellant) were amply made out. But on the questions of conduct, the court identified two particular periods of time where the court’s apparent inactivity caused unreasonable delay, the major one said to have been a failure over around three years to progress the appeal hearing once leave to appeal on all grounds had been granted. According to the European Court, article 6(1) required the domestic court “to adopt an active role in steering the appeal to a speedy conclusion”.

But exactly what the appeal court should have done is left unclear, as is what it could have done in the face of the appellant’s conduct throughout the appeal process. There were a number of separate strands to the appeal, at least some of which required to be litigated to a conclusion before the substance of the appeal became clear. Other strands turned on pending judicial decisions in other courts. The European Court appears to have recognised this, as did the Scottish court, but appears to have focused on what it saw as inadequate case management.

A final word

This has been my last column for Professional Briefing, before I pass the baton to Sheriff Frank Crowe with effect from February 2013. I take this opportunity to wish all readers of the Journal the compliments of the festive season.

In this issue

- Barriers to sibling contact

- Legal rights, second families and siblingship

- "I'm a chicklet and I live in a hatchery"

- And our survey says...

- No overtaking?

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion column: Martin Morrow

- Book reviews

- Council profile

- President's column

- 2012: new starts, and challenges

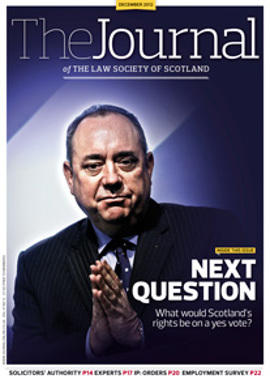

- Independence before the law

- Who do you think they are?

- The expert approach

- Is all publicity good publicity?

- Turning point?

- Young and guilty

- Doubly secure

- Forced marriage: an update

- New age, new image

- A security loophole

- Quit while you're ahead

- When threats are enough

- Practice ground

- Mergers: keeping people onside

- Law reform roundup

- PI Guidelines: new edition

- Ask Ash

- Business radar