Equal justice for all?

Shortly before Christmas, in the US state of North Carolina, Judge Gregory A Weeks gave a decision which carries hope for the future of a more equal justice system in North Carolina, one of 33 states which still have the death penalty in the US.

Judge Weeks held that under the North Carolina Racial Justice Act (“RJA”), race had indeed played a “significant factor” in the death sentences of three defendants, who although guilty of “heinous crimes”, were sentenced to death in a process that was focused more on obtaining their death sentences than ensuring a process that was fair and in accordance with the law. The key evidence for this? Handwritten notes, and spoken words of the prosecutors involved in all three separate cases, during the jury selection process. Notes which had long been buried in the case files and which were brought to light for the first time during the hearing, revealing evidence of race consciousness and race based decision-making in the prosecution’s jury selection strategy.

The decision was a closing victory for the group of attorneys who were representing the three (two African Americans and one Native American), who have now been removed from death row and instead face life without parole. It followed their earlier win in April, when Judge Weeks threw out the death sentence of Marcus Robinson, the first defendant to receive a hearing under North Carolina’s Racial Justice Act.

I started my legal internship with the Center for Death Penalty Litigation, who represented one of the three, in August. The CDPL specialises in post-conviction capital defence, and is based in the small town of Durham, former home to a thriving tobacco industry. It and other attorneys including from the American Civil Liberties Union were still enjoying the Robinson victory, but faced new uncertainty as to what would be the outcome for this group of RJA claimants, whose only connection was the racial bias which had characterised the jury selection in their trials. They were more than aware of the shaky political climate which had increasingly enveloped the RJA and which cast new doubt on whether the judge would reach a decision in their favour.

The Racial Justice Act – a leading example

Racism in the death penalty system is a nationwide problem that exists in the US today. North Carolina was the first state to enact a meaningful RJA of its kind in an effort to combat the prevailing prejudice that occurs in the issuing of death sentences in the state. A capital defendant can have his or her sentence reduced to life in prison without parole if there is evidence proving “that race was a significant factor in decisions to seek or impose the sentence of death in the county, the prosecutorial district, the judicial division, or the State at the time the death sentence was sought or imposed” (NC Gen Stat §15A-2010). It is sufficient to establish a violation of the RJA if there is evidence that race was a significant factor in either the charging of a defendant with a capital offence, the advancing of the case to a capital trial, or in the jury selection procedure.

The recent hearing was concerned specifically with the role that race played in this last category, and highlighted the lengths to which prosecutors will often go in order to disqualify non-whites from the jury.

“Top Gun” training: cheating constitutional rights

During jury selection in US capital trials, potential jurors are excused “for cause” when the judge finds that they cannot decide the case impartially. However, the prosecution and defence may each make a limited number of peremptory challenges to excuse additional jurors without offering a reason. In Batson v Kentucky (1986), the US Supreme Court introduced an important safeguard, recognising that this right was open to abuse. It held that the US Constitution promises a right to a jury made up of one’s peers, and that peremptory challenges cannot be used to systematically strike prospective jurors from the panel on the basis of race.

Since Batson, strikes against black jurors may be more easily challenged and the prosecution is compelled to respond with “race neutral” reasons. In reality, courts have generally been reluctant to enforce Batson strictly, and the RJA has enabled lawyers to approach the racial disparity in jury selection from a unique angle.

The prosecutor involved in all three cases discussed here had previously been found by a trial court to have violated Batson. Fast forward to the RJA hearing, where Judge Weeks found that she had overwhelmingly relied upon a “cheat sheet” of at-the-ready explanations, to defeat Batson challenges in numerous cases where her disproportionate and discriminatory strikes of black venire members (the jury selection pool) were called into question. The judge was referring to a popular training course that the prosecutor had attended, for North Carolina district attorneys – the “Top Gun” training course, where prosecutors learned not to examine their own prejudices or to present persuasive cases to a diverse cast of jurors, but rather how to circumvent the constitutional prohibition by using cheat sheets to offer purported “race neutral” reasons.

I prepared an exhibits file to accompany a post-RJA hearing briefing on disparate treatment of prospective black jurors, and from the many pages of jury selection transcripts that I read, it was clear that where black members were struck for their so-called death penalty views, criminal background, marital status, hardship, demeanour – reasons consistently cited by the prosecution – white members with comparable, and often more extreme, views or characteristics were overwhelmingly accepted.

RJA – past, present and... future?

The high-profile nature of the RJA proceedings could partly be linked to the controversy which has dogged the Act, particularly regarding its provision for use of statistical evidence to allow claimants to prove their cases. An extensive study was carried out by professors at the Michigan University Law School in order to evaluate the potential for statistical evidence to be used to support claims, and was used as evidence in court for the RJA proceedings. This led to accusations from the prosecution that the recent hearing was one based solely on numbers: statistics produced by non-lawyers, and forced into an inaccurate and incomplete study that doesn’t take into account the unique facets of jury selection in death penalty cases.

But if the numbers are telling the truth, over the 25 year period examined, eligible black jurors were struck at rates which were “statistically significant”. State wide, the average strike ratio was 2.5 compared to non-black jurors.

Despite the compelling results, North Carolina’s Republican-led General Assembly set about attempting to gut the RJA’s effectiveness and has all but succeeded in repealing the Act. A major revision was passed in June 2012, restricting the broad use of statistics in a case, limiting them instead to the specific county or jurisdiction of the crime. Statistics also need to be accompanied by evidence of intentional bias from the prosecutors or jurors.

The former Democratic governor, Bev Perdue, successfully vetoed the first attempt to amend the Act in this way, but not the second. Although a proponent of the death penalty, Ms Perdue was a supporter of the RJA and her second veto was overridden in a state where originally the governor’s powers were very weak – North Carolina was the last state to give its governors veto power over legislation, and it was not added to the constitution until 1996.

Hence, the question in the recent hearing was how the three death row inmates would have their sentences reviewed, in light of the amended RJA. The revised law makes clear the framework for future convicts, but it was unknown whether existing appeals made by prisoners would be upheld under the law at the time they applied, or under the scaled-back law. Judge Weeks’s decision put an end to the anticipation, concluding that the amended RJA does not explicitly extinguish previously-filed claims. Nor could the strength of the three claims be disputed, as the statements and handwritten notes more than satisfied the requirement for evidence of intentional bias in addition to clear and specific statistics – the case strike ratio for African Americans in one case was 3.7, a higher than average statistic with the result of an all-white jury.

However, it remains unclear how new judges will apply the law under this decision and what the framework will be for future defendants, many of whom committed their crimes long before the revision to the RJA. Judge Weeks is the only judge to have granted hearings and given relief under the RJA, and although he has opened the door for similar relief to be granted in future hearings, it is now in the hands of the other superior criminal court North Carolina judges as to whether they choose to do so. Also, the state will likely appeal to the NC Supreme Court, which could very easily overturn Weeks’s ruling.

A legacy of racial injustice

The RJA proceedings have highlighted an ugly truth – that race discrimination in America continues to influence a justice system that should be fair and equal for all. I have come to a far greater understanding of the roots of this issue in assisting the CDPL with its RJA casework, particularly whilst drafing an affidavit for Professor Tim Tyson, the author of Radio Free Dixie, a book about black civil rights activist Robert F Williams.

The aim was to detail the history of race relations in the district where the trial of a Native American client had taken place, and aside from being a fascinating insight into Williams’ life, the book reveals an America where the legacy of slavery and confederacy and the destructive impact of segregation have permeated law enforcement in the southern states, where non-whites have historically been the victims of an arbitrary and biased justice system.

Radio Free Dixie gave a startling account of the systematic violence that was unleashed against blacks and sometimes Native American tribes, violence which only escalated during the civil rights movement. Law enforcement officials rarely intervened in these kinds of attacks, and further prejudiced blacks in the interests of white people who often did not face consequences for their actions – Williams himself was arrested in 1961 without a warrant on the grounds of driving a car with broken tail lights, a result of having been rammed by a white man during demonstrations surrounding the building of a separate swimming pool for African American children.

A promise that must be kept

Judge Weeks’s decision has gone some way in attempting to restore integrity to a justice system that is far too frequently compromised by racial bias, and where the words “equal justice for all” under the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution have for many years carried little real meaning for African American citizens. He pointed out that racially discriminatory jury selection practices are at complete odds with America’s democratic heritage and representative government practices. He concluded that the central reason for the hearing and the presence of everyone in court that day awaiting his decision, came down to a simple question of “whether all members of the community can have trust and confidence that our system of justice will apply the law equally to everyone”. For this trust to exist, the operation of an even-handed justice system must be clearly perceived, as there “can be no trust and confidence in a system where those words are not backed by performance. Only performance is reality”.

Taken alone, these words carry a universal truth that is meaningful for all justice systems in societies which place value in democracy and fairness.

In this issue

- Remember, remember?

- Equal justice for all?

- Compatibility: devolution issues reborn

- Profiting from the past

- RTI for PAYE - are you ready?

- Reading for pleasure

- A modest proposal – civil marriage ceremonies for all

- Opinion column: Alistair Dean

- Book reviews

- Profile

- President's column

- Fee review: as you were

- Time to draw a line?

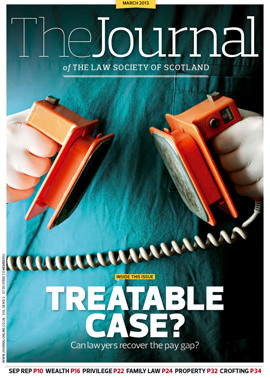

- The pay gap: seeking a cure

- Wealth management: Personal injury trusts - how to best invest

- Wealth management: Discretion - the model of choice

- Wealth management: Inheritance tax - discounts up front

- Wealth management: Pensions - time to look ahead

- Whose privilege is it, anyway?

- FLAGS unfurled

- Percentage game

- Rent, rent and rent again

- Sport, rights, and the internet

- An innocent mistake?

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- The trouble with in-house lawyers

- Lease of life for the High Street?

- PSG update

- Vacant and ready

- ABS in waiting

- Better ways: where to start?

- Keeping errors in check

- Ask Ash

- How not to win business: a guide for professionals

- What does a speculative fee allow?

- Law reform roundup