FLAGS unfurled

The implementation of the Arbitration (Scotland) Act 2010 opened the door to what is potentially the most significant change in the landscape in relation to adjudication of family law disputes since the Court of Session ceased to enjoy exclusive jurisdiction for divorce cases with their entry into the sheriff court in 1983.

The 2010 Act provides a framework for all arbitration work in Scotland. The primary legislation introduces a mechanism for enforcement and a route to appeal. It also provides a set of rules to be applied in the conduct of arbitration, although the use of the “default rules” accompanying the Act is not compulsory. Following the implementation of the Act, the Family Law Arbitration Group Scotland (FLAGS) was set up to promote the use and growth of arbitration as a vehicle for the resolution of family law disputes in Scotland, in both child and financial cases. (See interview feature, Journal, December 2010, 24.) FLAGS created a bespoke set of arbitration rules specifically for use in family law cases. Twenty-nine solicitors and advocates were subsequently trained as family law arbitrators and the scene was therefore set for family law arbitration to take off.

The writers – four solicitors in private practice who are FLAGS arbitrators and enthusiastic proponents of arbitration in family cases – are aware of a recently concluded arbitration, and there are more in the pipeline. It seemed timely, therefore, almost two years to the day after the first Scottish family law arbitrators were trained, to review the FLAGS scheme and how it works in practice.

Arbitration in the ADR spectrum

Arbitration will not be the panacea to cure all ills: it is simply one of the possible ways for disputes to be resolved. Many of the FLAGS arbitrators are also enthusiastic proponents of other forms of alternative (or “appropriate”, as it has become known) dispute resolution methods. All experienced family lawyers will tell you that the best possible outcome for clients is one that they have found themselves.

That is not always possible for all of our clients, however. Sometimes clients need somebody else to make a determination – they cannot agree, for example, whether it is best for their child to relocate to another jurisdiction, or they may feel unable to mediate or to utilise the collaborative family law model. What arbitration offers is an alternative to a court determination.

Procedure and practicalities

To a large extent the procedure in arbitration is flexible, although the FLAGS rules require that the arbitration be conducted without unnecessary delay and without incurring unnecessary expense.

The solicitors will complete the agreement to arbitrate. This sets out the scope of the arbitration, and in particular the matters in dispute. It is important that solicitors ask the arbitrator to determine the correct question. Instead of asking an arbitrator to determine the level of financial provision to be made upon divorce, for example, they should be asked to determine:

- What, if any, award of periodical allowance should be payable by party A to party B, and if any award is made, for what period is it payable?

- What, if any, capital sum payment should be made by party A to party B?

There will be a case management meeting (or meetings), with or without parties present, at which procedure will be determined. The case management meeting is very much to do with the active management of the case. The meeting would consider matters such as:

- What information is required to resolve the dispute?

- What timescales should be placed on the provision of information?

- How is evidence to be presented to the arbitrator? Will it be parole evidence or will it be by way of affidavit? Alternately, will the evidence be a mixture of affidavits and oral evidence?

- Should submissions be written, or oral? If the evidence and submissions are to be all written, what is the length for each document? Clearly, a case with the evidence restricted to six sides of A4 paper per party, and submissions likewise restricted, will be considerably cheaper to conduct than one where the evidence and submissions fill several lever arch files.

The arbitrator will determine whether evidence should be led, and if so, by whom and to what extent. At one extreme you can replicate a proof. At the other extreme all evidence can be given by affidavit. In between those extremes you could have parole evidence, but only from certain witnesses and on certain areas of dispute. You could also have all evidence in chief by way of affidavit, with the arbitrator “cross-examining” witnesses on their affidavits in order to clarify any remaining areas of dispute.

Is it right for your client?

Arbitration will not be right for every case. In the right cases, though, it has huge potential. As always, it involves you, as solicitor or counsel, working with your client to identify what will best serve their interests. There are advantages (and contra-indications) when it comes to a FLAGS arbitration.

Decision

If a determination is required – that is to say, the parties cannot find an accommodation themselves – arbitration will deliver that, the only other remedy being litigation. It is suggested that the determination in arbitration can be obtained more quickly, at less expense and with a more constructive approach than can be delivered through litigation (as it currently exists in family cases in Scotland).

Choice/expertise

The parties, unlike in a litigation, can select who they wish to be the decision maker. The 29 FLAGS arbitrators are, by definition, experienced lawyers with expertise in family law cases. These are individuals who practise family law, day in day out. Parties can select a decision maker who has particular experience in child cases or financial matters, who brings a particular approach to the arbitration and who will be responsible for the process from start to finish. There is also a broad geographical spread across the country so that individuals can choose a specialist decision maker who is local to them.

Privacy

A significant degree of privacy can be afforded by the arbitration process that parties cannot expect to enjoy in litigation. In an arbitration dealt with by the writer recently, privacy was a significant issue for the parties – they did not want it to be known that they were in dispute, let alone for the nature of their dispute to become public. The fact that the process itself was entirely private was an important selling point for them. The FLAGS model provides that registration of the decree arbitral will only take place if it is necessary for enforcement purposes.

The importance of privacy, it is suggested, is not simply an issue for high profile and/or wealthy individuals, but also for people who live in small communities where they do not want the details of their dispute to be in the local paper or the subject of tittle-tattle.

Flexibility and efficiency

One of the great advantages of the FLAGS arbitration model is that there is total flexibility in terms of how the dispute is resolved procedurally – as is dealt with in more detail earlier in this article. There is scope for a truncated process to be adopted which, it is suggested, may be particularly suitable for “single issue” matters. For example, if the parties cannot agree on what is the “relevant date”, that single issue could be remitted to arbitration on a papers-only basis; or if a decision has to be taken on whether there has been a “material change in circumstances”, that, again, can be referred to arbitration using an expedited process, perhaps with evidence being given by way of affidavit only, or with written submissions and then a brief oral hearing, at which the arbitrator adopts an inquisitorial role.

Cost

Cost is undoubtedly going to be one of the perceived benefits of arbitration. While parties obviously have to continue to employ agents and the costs of the arbitrator will have to be met, it is suggested that the inherently flexible procedure of a FLAGS arbitration will deliver an outcome for clients at a lower cost than if they were to litigate matters. The experience to date in Scotland, and, indeed, of our counterparts in England & Wales (where they adopted an arbitration scheme shortly after us which has some similarities) is that an arbitrated resolution will cost less than a litigated one.

Timely innovation

At a time when our courts are under increasing pressure and where our clients now, understandably, demand a commercially savvy approach to dispute resolution in a way that was perhaps not historically the case, the writers welcome the development of the FLAGS arbitration model. Notwithstanding the growth of mediation and collaborative family law, there will be cases where a determination is required. Arbitration may well bring that determination in a more dignified, timely and cost-effective fashion than the courts can currently deliver.

In this issue

- Remember, remember?

- Equal justice for all?

- Compatibility: devolution issues reborn

- Profiting from the past

- RTI for PAYE - are you ready?

- Reading for pleasure

- A modest proposal – civil marriage ceremonies for all

- Opinion column: Alistair Dean

- Book reviews

- Profile

- President's column

- Fee review: as you were

- Time to draw a line?

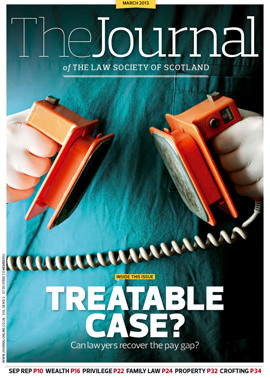

- The pay gap: seeking a cure

- Wealth management: Personal injury trusts - how to best invest

- Wealth management: Discretion - the model of choice

- Wealth management: Inheritance tax - discounts up front

- Wealth management: Pensions - time to look ahead

- Whose privilege is it, anyway?

- FLAGS unfurled

- Percentage game

- Rent, rent and rent again

- Sport, rights, and the internet

- An innocent mistake?

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- The trouble with in-house lawyers

- Lease of life for the High Street?

- PSG update

- Vacant and ready

- ABS in waiting

- Better ways: where to start?

- Keeping errors in check

- Ask Ash

- How not to win business: a guide for professionals

- What does a speculative fee allow?

- Law reform roundup