Sport, rights, and the internet

Large sporting events enjoy a rather unique approach in development. Rather than following a pattern of local establishment, then creation of goodwill, often it is the case that places bid for the right to provide an event with existing international recognition.

An entity is then established in the successful locale to run the event, running it under permission from the international rights holder. Registration of trademarks and domain names generally comes after the completion of the bid process, and rights registered generally tie back into the location and the intended year of the event.

This process can leave operating entities exposed. As bids are announced before they are established, the possibility of opportunistic third party brand registrations arises. Taking a traditional approach, difficulties could be foreseen in establishing and safeguarding rights in marks whose content is solely a place name and a year name, never before utilised in connection with the relevant event. This all adds to normal brand infringement risk. Particularly, risk lies online, given the low cost and simplicity of obtaining domain names.

Track record

Core to any large-scale event are “.com” names. The misregistration of “.com” names is primarily dealt with under the Uniform Domain-name Dispute Resolution Policy, as administered by a number of dispute resolution providers. The most prominent provider of dispute resolution services under the UDRP is the World Intellectual Property Organization. Core to achieving success in any dispute is demonstrating three key requirements – rights, bad faith and a lack of legitimate interest. Any practitioner can see that on the face of it, issues could arise under any of these headings, as a result of the peculiarities of large-scale sporting events. Key to advising in this field is knowing how WIPO has dealt with such issues previously.

First, WIPO has recognised the standing of local organising entities, as utilising years of goodwill surrounding the events in question under contract from ultimate rights holders. This was accepted in London Organising Committee of the Olympic Games and Paralympic Games Ltd v H&S Media Ltd. In addition, WIPO has recognised that local events are often referred to through the use of the location name and the year, and that third party use of this combination can be actionable. This was demonstrated in Melbourne 2006 Commonwealth Games Corporation v B & M Group Of Companies Pty Ltd; the London Olympics case mentioned above; Organising Committee Commonwealth Games 2010 Delhi v PrivacyProtect.org / netlinkblue digital energy (p) ltd; Madrid 2012, SA v Scott Martin-MadridMan Websites; and Organization Committee for the World Championship of Alpine Ski in 2009 v Kenney E Granum.

Preserving exclusivity

Often respondents will have tried to differentiate their domain name from the event through the use of additional wording or grammatical devices. Unfortunately for respondents, this does not lend them much support. In the London Olympics case mentioned above, the panel found that the additional presence of "my" was insufficient to add distinctiveness between a registered mark and a domain name in which it was reiterated. And in the Melbourne Commonwealth Games case the presence of an additional hyphen was found to be immaterial.

Use made of the domain name in question is also important. Where a respondent is deriving commercial gain (for example through the use of banner and per click advertising) from misdirected internet traffic, such use will generally be viewed as illegitimate. This is supported by the Delhi case mentioned above.

One must also consider the relationship between the respondent and the event. In the London Olympics case, the lack of any nexus between the respondent and the organising entity was important in the success of the complaint. In the Delhi case focus was made on the fact that the complainant had obtained the right to provide the event, and as such to use the name in question, under an international bidding process, thus making any claim of or interest in the name by the respondent inconceivable.

Lastly, it is worth noting the Madrid case, and its comment on anticipatory registrations. This case dealt with a registration actioned before registered trademarks relating to the event were applied for, and before the organising company was renamed to use the event mark. Notwithstanding this, the complaint was successful. Speculative registrations relating to large-scale events can certainly be dealt with.

In essence, the approach of WIPO in relation to large-scale sporting events shows a willingness to recognise rights and an entitlement to exclusivity. This is an approach which should be welcomed by events rights owners.

In this issue

- Remember, remember?

- Equal justice for all?

- Compatibility: devolution issues reborn

- Profiting from the past

- RTI for PAYE - are you ready?

- Reading for pleasure

- A modest proposal – civil marriage ceremonies for all

- Opinion column: Alistair Dean

- Book reviews

- Profile

- President's column

- Fee review: as you were

- Time to draw a line?

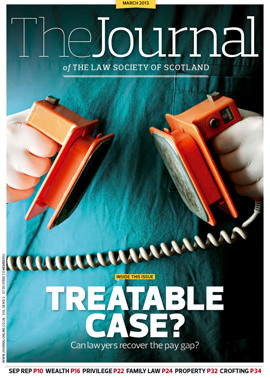

- The pay gap: seeking a cure

- Wealth management: Personal injury trusts - how to best invest

- Wealth management: Discretion - the model of choice

- Wealth management: Inheritance tax - discounts up front

- Wealth management: Pensions - time to look ahead

- Whose privilege is it, anyway?

- FLAGS unfurled

- Percentage game

- Rent, rent and rent again

- Sport, rights, and the internet

- An innocent mistake?

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- The trouble with in-house lawyers

- Lease of life for the High Street?

- PSG update

- Vacant and ready

- ABS in waiting

- Better ways: where to start?

- Keeping errors in check

- Ask Ash

- How not to win business: a guide for professionals

- What does a speculative fee allow?

- Law reform roundup