DPAs: cross-border confusion?

Corporate wrongdoing and scandals emanating from the recession have resulted in the public and politicians being increasingly concerned about “white collar” and corporate crime. In an attempt to improve the success rate for dealing with economic crimes committed by companies, new US-style deferred prosecution agreements (“DPAs”) will soon be introduced in England & Wales.

DPAs are being introduced under sched 17 to the Crime and Courts Act 2013 (“CCA”), which received Royal Assent on 25 April 2013. DPAs may be an enforcement tool available in England & Wales from early 2014.

So what is a DPA, and should the Scottish Government consider their introduction in Scotland?

Deferral: the basics

DPAs will allow a prosecutor and an organisation to agree that the prosecutor will lay, but not immediately proceed with, criminal charges pending compliance by the organisation with specified conditions. These conditions may include payment of substantial fines, compensation of victims, and submitting to compliance measures such as a monitoring regime.

If the prosecutor is satisfied that the organisation has fulfilled the conditions by the end of a set period, there will be no prosecution. If the conditions are not met, the original prosecution may be revived.

DPAs can be entered into by a body corporate, a partnership or an unincorporated association in relation to a range of financial crimes including fraud, bribery, proceeds of crime offences and certain offences under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 and the Companies Act 2006.

Detailed joint guidance from the Director of Public Prosecutions and the Director of the Serious Fraud Office (“SFO”) is expected to set out much of the detail on how DPAs will operate later this year.

A good thing?

Ministry of Justice consultation

According to the UK Ministry of Justice, the push to adopt DPAs in England & Wales received widespread support during consultation on the CCA from prosecutors, businesses, the legal profession, regulatory bodies and members of the public, with 86% of respondents agreeing that DPAs have the potential to improve ways of dealing with corporate economic crime.

Civil settlements

Prosecutions of companies for economic crimes are inherently difficult, as the prosecution often need to prove that a “directing mind” was personally guilty of an offence to attribute guilt to the corporate body. That necessitates a large scale investigation, involving trawls of emails and financial records and interviews of numerous personnel. Proving a corporate criminal case is resource-intensive and evidentially challenging.

It was also recognised by the Ministry of Justice that criminal investigations and prosecutions of companies for economic crimes can be extremely damaging to companies and, importantly, for innocent employees. A conviction of a company for the economic crimes of fraud, money laundering, or bribery could have significant consequences, including debarment from public sector contracts in the EU and US, and withdrawal of lending facilities (a criminal conviction for bribery or fraud is a standard default event in facility agreements).

As such, prosecutors in both Scotland and England & Wales increasingly consider civil recovery under part 5 of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002, or civil settlements, as an alternative to criminal investigation of a company that has benefited from criminal conduct.

On 1 July 2011, Crown Office issued guidance to businesses on self-reporting bribery offences in return for an opportunity to settle, on a civil basis, any corporate criminality. That guidance was similar to guidance issued by the SFO in England & Wales. A handful of companies have agreed civil settlements with the SFO, and there has been one concluded corporate settlement in Scotland. Crown Office’s self-reporting initiative runs until 30 June 2013, when it may or may not be renewed. The SFO’s approach will be superseded by DPAs.

A criticism of civil recovery and settlement is that it focuses on removing tainted proceeds only. It does not enable punishment of wrongdoing or compensation of victims, and there is limited scope for conditions regarding remedial measures unless the parties agree. Another common criticism is that civil settlements lack transparency and judicial scrutiny.

DPAs will allow prosecutors to hold offending organisations to account by recovering tainted proceeds, the imposition of penal fines, and measures designed to prevent recurrence, but without the uncertainty, expense, complexity or length of a criminal investigation and trial. They should enable swifter restitution and rehabilitation and reduce risks to innocent directors, employees and stakeholders. DPAs will be subject to judicial approval, and details of the wrongdoing and sanctions will be published, which should lead to greater transparency and consistency around the penalties levied for corporate crimes.

Corporate crime detection

The UK’s Ministry of Justice considers that corporate offending is currently underreported and underenforced, due to the inadequacy of the tools currently available to law enforcement and the lack of incentives for a company to self-report criminal conduct.

Currently the prospect of obtaining a civil settlement is inherently uncertain, and corporate self-reporting is not for the faint hearted. As such, the number of companies self-reporting remains low. It is clear that the intention is that DPAs will be used in the majority of economic crime cases involving bona fide companies in England & Wales, as they currently are in the US. DPAs are being introduced, in part, to promote a culture where companies are more willing to confess to criminal misconduct.

DPAs will make joint settlements with the SFO and the US Department of Justice more readily achievable, and should give rise to greater prospects of a “global settlement” being achieved.

In the US, self-reporting the discovery of criminality implicating the corporate body is commonplace. The main reason that companies self-report in

the US is that it increases the certainty of the enforcement outcome and that considerable credit for doing so is given, with DPAs and, indeed, non-prosecution agreements being commonplace. In turn, the fact that companies self-report misconduct provides valuable intelligence to law enforcement that other parties to a transaction, supply chain, or sector may also be involved in criminality. There is therefore an increased risk of detection. The fines and restitution paid by companies subject to US enforcement can be significant. The risk of detection, coupled with the sanctions imposed on companies, has led to US companies prioritising compliance and the promotion of business ethics.

Scottish position

One source of uncertainty for businesses operating throughout the UK is the fact that it is not currently intended to introduce DPAs north of the border.

Shortly before the CCA received Royal Assent, a Scottish Government spokesperson said: “While we are aware of the UK Government’s plans, we do not have any immediate plans to legislate for deferred prosecution agreements for Scotland. We will continue to monitor developments in England & Wales.”

This gives rise to cross-border issues. Crimes committed by UK companies are often subject to concurrent jurisdiction, meaning that both the SFO and CPS in England & Wales and the Crown Office in Scotland are entitled to prosecute.

For example, as matters currently stand, the SFO and Crown Office have concurrent jurisdiction in relation to bribery committed overseas by UK companies.

Having DPAs in England & Wales but not in Scotland risks ambiguity and uncertainty for businesses operating in both jurisdictions, and may undermine any incentive to self-report.

It is unclear for businesses operating on both sides of the border whether DPAs entered into with the SFO in London will be respected by the Scottish authorities. The flip side is that the difference in approach north and south of the border could lead to a rise in “forum shopping” among guilty corporates, who agree to a DPA in England to avoid prosecution in Scotland under a double jeopardy-type argument, thereby denying Scottish prosecutors the chance to secure restitution, compensation, or convictions.

Call for action

In its consultation paper on DPAs, the UK Ministry of Justice stated that it was discussing the application of DPAs with the devolved administrations.

DPAs for serious criminal conduct by companies will soon be a reality in England & Wales. As the introduction of DPAs will impact on Scottish companies and their professional advisers, clarity is needed as to how DPAs will work in cases of concurrent jurisdiction within the UK.

In the authors’ opinion, there are cogent grounds for the Scottish Government to legislate to introduce DPAs into Scotland.

In this issue

- Risk and the duty to inform

- Decrofting back on track

- The long road to qualify

- Scotland scores on “Themis” debut

- Equality and regulatory reform

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion column: Martin Crewe

- Book reviews

- Profile

- President's column

- What right of way?

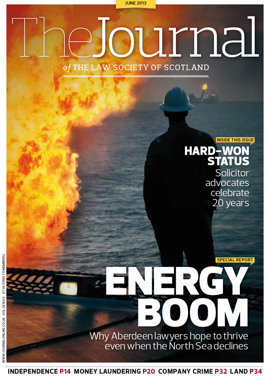

- Gas in the tank

- Scotland on the world stage

- Up there with the best

- The Significant Seven

- Out on 65?

- Gatekeeping the experts

- Fairway failings

- Beware of solvent liquidations

- Passing off update

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Holyrood out of bounds

- DPAs: cross-border confusion?

- The road to land reform, but where is it going?

- How not to win business: a guide for professionals

- Information security: raising the bar

- Waste: help sort it out

- Where there's a will

- Ask Ash

- "Reply to all"

- Law reform roundup

- Incidental financial business: amendments ahead

- Times are tough