Gatekeeping the experts

Expert evidence

The case of Hainey v HM Advocate [2013] HCJAC 47 (18 April 2013) attracted a lot of publicity at the time of the trial, as the appellant was convicted of murdering her infant son by neglecting him and failing to secure medical attention.

Social workers had made various attempts to see the appellant and her child, and eventually when access was gained to the house it was found in a chaotic state and the child’s badly decomposed body was found in a cot. It was a matter of agreement that after a post mortem, pathologists had reported the child’s cause of death as being unascertained.

The Crown led two forensic anthropologists, who had no medical qualifications but who said that their examinations revealed “cortical erosion” and “Harris” lines which might be indicative of pre-death stress arising from neglect and malnutrition. The trial judge in his report to the appeal court recognised this evidence was of considerable significance.

The appellant’s evidence was that she had put her son to bed in his cot one night, and the next morning had found him dead.

She had been unable to bring herself to tell anyone, and later relapsed into drug abuse. The Crown deleted the reference to “assault” in the libel at the conclusion of the prosecution case, and a submission of no case to answer was rejected.

At the conclusion of the defence case a further submission was made that the judge should direct the jury to disregard the forensic anthropologists’ evidence, as they did not have the requisite degree of expertise and their evidence fell below the standards required of an expert witness. It was also said that the witnesses did not corroborate one another. This submission was rejected and subsequently the appellant was convicted on a majority verdict.

In his charge the trial judge directed the jury to “scrutinise the chapter of evidence relating to Harris lines and cortical erosion with great care. You must decide what weight, if any, it should have”.

The appeal court referred to Liehne v HM Advocate 2011 SCCR 419 at para 49, which states that where there is, on the evidence, a realistic possibility of there being an unknown cause of death, the jury should be reminded that this must be excluded before they can convict and “it will be for the trial judge to provide a succinct, balanced review of the central factual matters for the jury’s determination”.

The court was of the view that the judge’s remarks covering the expert evidence in the circumstances had been inadequate. In quashing the conviction, the court (at para 52) suggested that guidance on expert evidence of the type contained in R v Henderson (Practice Note) [2010] 2 Cr App R 24 should be applied in Scotland, whereby medical evidence sought to be relied on is considered at a pre-trial hearing. At such a hearing the judge would be required to act as a “gatekeeper”, scrutinising qualifications and experience and if necessary excluding expert evidence. At present, expert reports are often lodged late after procedural hearings and shortly prior to trial, which can give rise to problems of the sort that emerged at this trial.

This case does highlight the tensions between the traditional approach laid down by Lord Justice General Cooper in Simpson v HM Advocate 1952 JC 1 at 3, that the presiding judge may review and comment on the evidence, but “the utmost care should be taken… to avoid trespassing upon the jury’s province as masters of the facts”, and the more modern necessity to take positive steps to ensure the accused receives a fair trial under article 6 ECHR.

The case is also significant for the subsequent statement issued by the Judicial Office commenting on remarks in para 49 of the opinion about the expert witnesses: see www.scotland-judiciary.org.uk/24/1032/KIMBERLEY-HAINEY-v-HMA

Circumstantial evidence

In Reference by the Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission in the case of Chamberlain-Davidson [2013] HCJAC 54 (5 February 2013), the appellant had been convicted of assault with intent to rape in 2006. Various grounds of challenge were put before the Commission. It was a matter of concession that the appellant’s police interview fell within the ambit of Cadder v HM Advocate [2010] UKSC 43; 2011 SC (UKSC) 13.

The appeal court considered whether the remaining evidence amounted to a sufficiency. The complainer alleged that she had been accosted by the appellant while out walking; as he approached her he said he wanted sex and seized her by the wrists. She screamed, struggled and managed to escape into a nearby car park and into the arms of a woman who had heard screams and alighted from her car. The woman had seen the appellant leaving the car park earlier in the direction the complainer had come from, and afterwards return to the car park and act in a furtive manner. The complainer spoke of a white van driving past her twice in a short space of time on the single track road she had been walking; the appellant’s van had been parked close to the locus.

The advocate depute highlighted that the complainer’s cardigan and sunglasses had been found at the locus by police and that she had been very distressed when police were called to the scene.

The court held that the complainer’s evidence was not corroborated on the essential matter that she had been assaulted. Her distress only confirmed that something distressing had occurred. The circumstances did not provide corroboration; the recovery of the cardigan and sunglasses did not advance matters.

The case provides a helpful discussion of the value of distress as evidence, and consideration of the evidential elements in a thin/circumstantial case and whether they established the facta probanda of the particular offence.

Maximum sentence on complaint

The appellant in Jones v Procurator Fiscal, Dundee [2013] HCJAC 53 (4 December 2012) pled guilty at the outset to a charge of assault and a contravention of s 38(1) of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 2010 (threatening behaviour). He was sentenced to six and four months respectively, to run consecutively. In recognition of the early pleas the sentences had been discounted from nine and six months respectively.

Founding on Nicholson v Lees 1996 SCCR 551, the appeal court confirmed that it was incompetent to impose a total period of imprisonment on a complaint which exceeded the 12 month maximum, as the headline sentences selected had. The position differs at sheriff and jury level, where the court can select a headline sentence above the maximum, provided the discounted level is within the five year maximum, on the basis that the accused could have been remitted to the High Court for sentence: McGhee v HM Advocate 2006 SCCR 716. The appeal court substituted sentences of six and two months, discounted from nine and three months.

What is a sexual offence?

This question was raised again in Scott v Procurator Fiscal, Glasgow [2013] HCJAC 52 (10 May 2013), where an employee was approached while changing in the staff toilets by her boss. When the appellant entered the toilet the complainer was only wearing her underwear. The appellant made a comment about the underwear and made to touch it, but did not. The sheriff convicted him of sexual assault contrary to s 3 of the Sexual Offences (Scotland) Act 2009 by attempting to touch the complainer.

The appeal court quoted from the legislation at length, pointing out the essential components of the offence, including in this case the requirement of touching. The lack of reasoning for convicting of the sexual offence was also the subject of criticism. While the appeal court suggested it might have been possible in the circumstances to have convicted of an attempted assault at common law, the conviction was quashed.

Applications for extensions of time

At one time, late leave to appeal seemed to be granted in most cases, but in recent years time limits have hardened. Macdonald v Procurator Fiscal, Dornoch [2013] HCJAC 48 (13 March 2013) concerned an application for extension of time to lodge a bill of suspension, and Middleton and McAllister v Procurator Fiscal, Livingston [2013] HCJAC 49 (13 March 2013) a similar application in respect of a bill of advocation.

In MacDonald, trial took place on 30 October 2012 and after conviction sentence was passed on 24 December. The bill of suspension was not presented until 25 February 2013.

It was averred that a police witness had stared and smirked at the appellant’s mother as she gave evidence at the trial, and as a result she was distracted and intimidated. This conduct had not been observed by anyone else in court apart from the witness. The court held that no adequate explanation was proffered for the bill’s late submission and the circumstances lacked merit.

In Middleton, the bill of advocation was taken when the sheriff adjourned the case for “an extraordinary fifth time for the same apparent reason of ‘lack of court time’”. The court pointed out, however, that the time limit for lodging such an application was three weeks, as a result of s 191A of the 1995 Act having been amended by s 6 of the Criminal Procedure (Legal Assistance, Detention and Appeals) (Scotland) Act 2010. The explanation that one of the local agents was not aware of the new time limit was not deemed a satisfactory excuse.

In this issue

- Risk and the duty to inform

- Decrofting back on track

- The long road to qualify

- Scotland scores on “Themis” debut

- Equality and regulatory reform

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion column: Martin Crewe

- Book reviews

- Profile

- President's column

- What right of way?

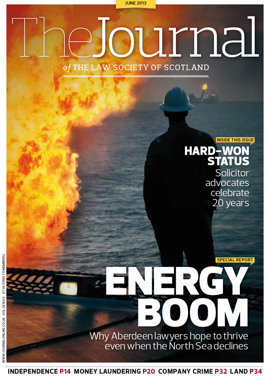

- Gas in the tank

- Scotland on the world stage

- Up there with the best

- The Significant Seven

- Out on 65?

- Gatekeeping the experts

- Fairway failings

- Beware of solvent liquidations

- Passing off update

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Holyrood out of bounds

- DPAs: cross-border confusion?

- The road to land reform, but where is it going?

- How not to win business: a guide for professionals

- Information security: raising the bar

- Waste: help sort it out

- Where there's a will

- Ask Ash

- "Reply to all"

- Law reform roundup

- Incidental financial business: amendments ahead

- Times are tough