Holyrood out of bounds

On 24 April 2013, the Supreme Court handed down its judgment in the long running case of Salvesen v Riddell, in an appeal (heard on 12 and 13 March 2013) by the Lord Advocate against the decision (on appeal) of the Second Division of the Court of Session, on 15 March 2012.

Legal framework

Section 72 of the Agricultural Holdings (Scotland) Act 2003 provides that where a lease of an agricultural holding to a limited partnership is brought to an end as a result of the dissolution of the partnership by the limited partner, by notice of dissolution (or some other action), the general partner may serve a counter-notice claiming the tenancy as an individual. In that case, the general partner becomes the tenant, but subject to the right of the landlord (s 72(10) of the 2003 Act) to terminate the lease in a comparatively short space of time, by the double notice procedure set out in s 73.

An exception was made, however, where the notice of dissolution of the partnership, or other qualifying action by the landlord, was taken before 1 July 2003. In that case, if the general partner claims the tenancy, the landlord’s right to terminate the tenancy under s 73 does not apply (and the lease, accordingly, becomes a fully protected 1991 Act lease with all its consequences, including security of tenure, succession rights and agricultural tenant’s right to buy), unless the landlord can, on application, obtain an order from the Scottish Land Court to the effect that dissolution was for a purpose other than to deprive the general partner of his rights under s 72 and that it is reasonable for the court to make the order.

To the Land Court

On 3 February 2003 Mr Salvesen, the owner of Peaston Farm, East Lothian, served notice on the Riddells, the general partners of the limited partnership which was the tenant of the farm, dissolving the partnership on 28 November 2008. In doing so, Mr Salvesen acted lawfully at the time, along with very many other landlords in Scotland, to protect himself against what later became s 72 of the 2003 Act, but which, at that stage, was one of a set of proposed amendments to the legislation – the exception for notices served/actions taken before 29 July 2003 was not included until the final stage (stage 3) of the legislative process, specifically as a result of the dissolution notices served by limited partners on 3 February 2003.

On 12 December 2008, Messrs Riddell gave counter-notice under s 72, claiming a joint tenancy of the farm in their own right. The landlord applied to the Land Court for an order that his purpose in terminating the lease (by dissolving the partnership) had been to amalgamate Peaston Farm with adjoining in-hand farms to form a single unit and, therefore, not to deprive the Riddells of their rights under s 72.

The Land Court found (after debate) that the dissolution notice had been served in order to defeat the general partners’ s 72 rights, without allowing the landlord a proof on his averments as to his intention to amalgamate the farm. The Riddells, therefore, acquired a secure tenancy of the farm and the landlord lost any right to terminate it under s 73.

It should be noted that the human rights issues, considered in the subsequent appeals, were not argued in the Land Court.

Human rights in the Inner House

Mr Salvesen appealed to the Court of Session on two grounds. First, the Land Court erred in deciding that the dissolution of the partnership had been to deprive the general partners of their rights without allowing a proof. Secondly, his rights under article 1, Protocol 1, of the European Convention on Human Rights to enjoy peaceful enjoyment of his possessions and, under article 14, to do so without discrimination, had been breached, with the result that the relevant statutory provision, at the time at which it was made law by the Scottish Parliament, had been outside the Parliament’s competence, given its obligation under the Scotland Act 1998 to enact legislation that is human rights compliant.

The Second Division upheld Mr Salvesen’s contentions on both counts. It remitted the case back to the Land Court for a hearing on his averments that his purpose in dissolving the partnership (and accordingly the lease) had been amalgamation. Although, in such circumstances, the court was not technically required to do so to decide the case, it took the view that the human rights issues were of such importance and general interest that it should deal with them.

That it did in some detail, coming to the conclusion that Mr Salvesen’s human rights had indeed been breached by the exception to s 72 and that, as a result, it had been outside the legislative competence of Parliament to enact the provision concerned. The Court of Session did not, however, go on to consider how the defect might be remedied.

The Supreme Court’s approach

Having been granted leave by the Second Division to do so, the Scottish Government appealed to the Supreme Court.

The court, first of all, rejected the Lord Advocate’s contention (for the Government) that the Second Division’s finding that the landlord’s rights were violated had been premature and unnecessary in respect that it had remitted the case back to the Land Court for proof on the landlord’s averments on why the partnership had been dissolved. That issue was, in the Lord Advocate’s view, pending before the Land Court. If the Land Court were to uphold the landlord’s contentions, that would mean an end to the case without the necessity to consider other issues.

The Supreme Court decided, however, that things had moved on, the parties having, in the intervening period, settled their differences by agreement. There was, accordingly, no longer any need for the case to be further considered by the Land Court. The human rights issues were, on the other hand, of general public interest and should, therefore, be resolved.

The court also agreed with the Second Division that the landlord’s human rights had been breached, not, however, by the exception itself but by the deprivation of the landlord of the right (available to other landlords under s 72(10) of the 2003 Act whose general partners had claimed tenancies in their own right) to terminate the tenancy under s 73.

The court based its conclusion primarily on the enacted provisions themselves, placing less emphasis than the Second Division on policy and other statements by ministers which had been made at the time that the legislation was going through the Parliament and which the Court of Session had called “immoral”. The Supreme Court regarded the different treatment of landlords who had served their notices before and after 29 July 2003 as being “without logical justification” and “unfair and disproportionate”.

It agreed with the Second Division that s 72 could be read only in a way which was incompatible with the article 1, Protocol 1, Convention right. While it was plain to the court that s 72 as a whole, and its relationship with s 73, needed to be looked at again, the finding of incompatibility ought not to extend any further than necessary to deal with the facts of the case, so that accrued rights which are not affected by the incompatibility are not interfered with. As it arose from the fact that s 72(10) excluded landlords whose notices were served before 29 July 2003 from exercising the right (extended to other landlords) to terminate the tenancy, the court limited its decision about the lack of legislative competence to that subsection alone.

Sort it out

Unlike the Second Division, the Supreme Court was fully addressed by counsel on the options available under the Scotland Act for rectification of the defect. After detailed consideration of the appropriate provisions, the court made an order postponing the effect of its finding that s 72(10) of the 2003 Act is outside the legislative competence of the Parliament for 12 months (or such shorter period as may be required), for it to be corrected and for that correction to take effect.

Finally, the court gave its permission to the Lord Advocate to apply to the Court of Session for any further orders under the Scotland Act that may be needed in the meantime to enable the Scottish ministers to make the correction before the suspension comes to an end – for example if that period needs to be extended.

Grounds for claim?

Clearly, the decision by the highest court in the land is of great significance not only for agricultural law but also as a matter of constitutional importance. The Scottish Parliament has been found to have acted outwith its competence – i.e. unlawfully. The consequences will, no doubt, reverberate for some time and developments on how the Scottish Parliament intends to remedy the defect in its own legislation are awaited with interest. This will involve questions of policy (not simply drafting) and consultation.

At the same time, agents should consider whether clients (both landlords and tenants) who have already made other arrangements to avoid the potentially long term damage to their interests presented by s 72(10) may have suffered loss and, if they have, whether they may have claims for compensation against the Scottish Government.

In this issue

- Risk and the duty to inform

- Decrofting back on track

- The long road to qualify

- Scotland scores on “Themis” debut

- Equality and regulatory reform

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion column: Martin Crewe

- Book reviews

- Profile

- President's column

- What right of way?

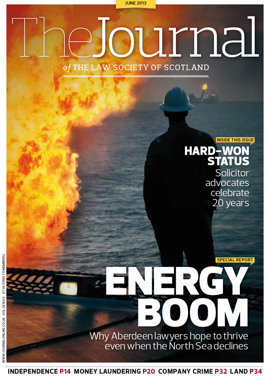

- Gas in the tank

- Scotland on the world stage

- Up there with the best

- The Significant Seven

- Out on 65?

- Gatekeeping the experts

- Fairway failings

- Beware of solvent liquidations

- Passing off update

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Holyrood out of bounds

- DPAs: cross-border confusion?

- The road to land reform, but where is it going?

- How not to win business: a guide for professionals

- Information security: raising the bar

- Waste: help sort it out

- Where there's a will

- Ask Ash

- "Reply to all"

- Law reform roundup

- Incidental financial business: amendments ahead

- Times are tough