Passing off update

Significant changes to UK IP law are on the horizon. The Enterprise and Regulatory Reform Act 2013 provides for enabling legislation to reform copyright law. The upcoming Intellectual Property Bill will reform patent and design law. Detailed analysis will follow once legislation has been finalised.

For now, we consider two recent English decisions which clarify important aspects of passing off: the honest concurrent use defence, and extended passing off.

Honest concurrent use

In WS Foster & Sons v Brooks Brothers UK [2013] EWPCC 18, the Patents County Court examined the circumstances in which the “honest concurrent use” defence is available.

The claimant, Foster, has produced and sold leather products in the UK since the 1800s. Brooks Brothers has traded in the US since the 1800s. In 2005 it began trading in the UK. Its UK subsidiary was the defendant.

For years, Foster and Brooks used the same logo (“the Brand”) on their shoe products. When Foster became aware that Brooks UK was using the Brand, it raised passing off proceedings.

Both companies considered they had a legitimate reason to use the Brand, formerly the logo of a company, Peals, which ceased trading in 1964. Brooks Brothers purchased the rights in the Brand from Peals and continuously used the Brand on shoe products in the USA from 1964 onwards. However, Brooks UK did not start using the Brand until 2005.

When Peals went out of business, Foster employed a former Peals bootmaker. Foster continuously used the Brand in the UK from 1965 onwards to denote this link.

Discussion

Brooks UK defended the proceedings on the ground of its honest concurrent use. The court held that this defence required three elements to be present:

- the first use of the Brand in the UK by the defendant had to be entirely legitimate;

- by the time of the alleged passing off, the defendant had to have acquired its own protectable goodwill in the Brand; and

- the defendant’s acts amounting to alleged passing off had to be not materially different to its prior legitimate use of the Brand.

The court held that Brooks Brothers had abandoned the UK goodwill in the Brand in 1965. It could not prove use of the Brand in the UK between 1965 and 2005. As such, it could not show that it had any goodwill in the Brand in the UK, so failed to establish the second element of the defence.

As well as providing a helpful summary of the defence, this case highlights the territorial nature of goodwill. A strong overseas reputation in a brand will not necessarily give a foreign company automatic rights to use that brand in the UK.

It is also a reminder that after a business has acquired goodwill as an asset, it must be careful not to abandon it. In other words, “use it or lose it”!

Extended passing off

In Fage UK v Chobani UK [2013] EWHC 630 (Ch), the court clarified the circumstances in which a class of products will qualify for “extended passing off” protection.

Extended passing off protects goodwill in trade names which describe a class of products, such as “Scotch whisky”, “champagne”, “Parma ham” or “Swiss chocolate”. Any producer of the product can sue a third party who uses the term to describe non-genuine products.

Fage manufactured Greek yoghurt. In the UK a practice had evolved whereby only yoghurt made in Greece manufactured by straining was described as “Greek yoghurt”. Similar yoghurt produced outside Greece and/or using different techniques was described as “Greek-style”. Chobani produced strained yoghurt in the US and sold it in the UK as “Greek yoghurt”. Fage sued for extended passing off.

Discussion

The court clarified the requirements for extended passing off protection:

- the trade name must mean more to consumers than just a description of geographical origin. It must have pulling power for consumers; and

- a significant section of the public must believe the name denotes a sufficiently defined and distinctive class of goods.

The court heard evidence that over 50% of consumers of Greek yoghurt believed it came from Greece, and that this mattered to them. They did not have a consistent understanding of the other differences between Greek and Greek-style yoghurt. However, the “Greek yoghurt” description had a pulling power which brought in custom, so it was more than simply descriptive of territorial origin and could be protected by injunction to stop Chobani describing its US-manufactured product as Greek yoghurt.

The case provides useful guidance on the availability of extended passing off rights. Significantly, the informal labelling practice adopted by UK producers, coupled with the public perception of its meaning, was sufficient to give rise to protectable rights. Many manufacturers seek EU protected geographical indication (“PGI”) or protected designation of origin (“PDO”) status for their products, most recently Stornoway black pudding. Such statutory protection is hugely valuable, but can be difficult to obtain. The power of common law extended passing off protection should not be underestimated.

In this issue

- Risk and the duty to inform

- Decrofting back on track

- The long road to qualify

- Scotland scores on “Themis” debut

- Equality and regulatory reform

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion column: Martin Crewe

- Book reviews

- Profile

- President's column

- What right of way?

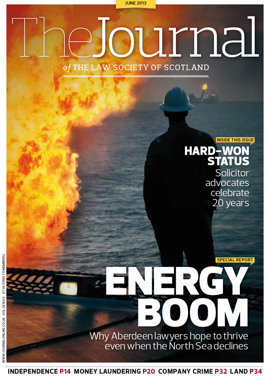

- Gas in the tank

- Scotland on the world stage

- Up there with the best

- The Significant Seven

- Out on 65?

- Gatekeeping the experts

- Fairway failings

- Beware of solvent liquidations

- Passing off update

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Holyrood out of bounds

- DPAs: cross-border confusion?

- The road to land reform, but where is it going?

- How not to win business: a guide for professionals

- Information security: raising the bar

- Waste: help sort it out

- Where there's a will

- Ask Ash

- "Reply to all"

- Law reform roundup

- Incidental financial business: amendments ahead

- Times are tough