Scotland on the world stage

Although the creation of states is primarily a political process, it takes place within the legal context provided by international law. The prospect of Scottish independence inevitably gives rise to questions as to how the new state would operate within the international legal system. This short commentary will provide an overview of the international law context within which Scotland would need to operate.

It should be stated at the outset that, on independence, Scotland would fulfil all the criteria for statehood as set out in article 1 of the 1933 Montevideo Convention on Rights and Duties of States. These include: (i) permanent population; (ii) defined territory; (iii) government; and (iv) capacity to enter into relations with other states. Scotland’s territory would consist of its land, its territorial waters (up to 12 nautical miles), as well as the airspace above its land and territorial waters. Any territorial disputes that might arise would not affect this criterion, but highlight the importance of boundary delimitation. Scotland’s population would be that determined by its internal law on nationality/citizenship, and Scotland’s Government would be independent and able to exercise effective control over its territory and people.

Recognition and its consequences

When a new state comes into being, the issue of recognition by other states arises. Recognition means willingness by other states to deal with the new state, and the prevailing view today is that recognition is declaratory and not constitutive of the state.

“Regarding membership of NATO, this would be effected if Scotland fulfils all the conditions set out in the membership action plan as agreed by Scotland and NATO”

Recognition is a political act. For instance, certain states might refuse to recognise Scotland if in their opinion the declaration of independence constituted a precedent that might fuel domestic demands for independence.

Although a political act, recognition produces legal effects in international and domestic law.

As far as the international law effects of recognition are concerned, a recognised state can enter into legal and political relations with other states, whereas a non-recognised state cannot enter into legal or political relations with those states that refused to recognise it. That having been said, some form of contact and relations may be established out of necessity. In this case we can speak of de facto recognition of a new state.

Concerning the domestic effects of non-recognition, the situation varies. Some states follow the “no recognition, no existence” rule, according to which none of the legislative, executive, judicial or administrative acts of the unrecognised state would be accepted as valid by national courts and the unrecognised state cannot sue or be sued before national courts. Other states recognise only private acts (registration of births, deaths, marriages, contracts) by the non-recognised state; yet other states recognise the law of the unrecognised state if the executive confirms that this is not harmful to its foreign policy.

A non-recognised state is still a state for international law purposes, and its relations with other states – including those that have not recognised it – are regulated by general international law. For example, the rule on the non-use of force will apply as customary law to the relations between the unrecognised state and all other states.

Seeking membership

If it became a new state, Scotland should become an active member of the international society by joining international organisations. Membership of international organisations takes place according to the criteria laid down in the constitutive treaty of the referent organisation or the criteria established by the organisation’s practice, and these may differ from organisation to organisation.

As far as the United Nations is concerned, the membership criteria are laid down in article 4 of the UN Charter. According to this article, the candidate must be a peace-loving state which accepts the obligations of the Charter and is able and willing to carry them out.

In the event of independence, Scotland should submit an application to the Secretary-General containing a declaration of acceptance of the obligations contained in the UN Charter. Its application would be scrutinised by the Admission of New Members Committee and be transmitted to the Security Council. On a positive recommendation of the Security Council, it would be discussed by the General Assembly (GA), which would make the final decision. The GA’s decision should be made by a two-thirds majority of the present and voting members.

There is no doubt that Scotland would fulfil the admission criteria, and it is highly unlikely that any state would veto its application.

The political and legal aspects of Scotland’s membership of the EU have been discussed quite extensively in different fora, including this Journal (Livingstone, “Independence before the law”, Journal, December 2012, 10; Edward (interview), “All in the same boat”, Journal, February 2013, 15). For this reason, there is no need to repeat the arguments for or against automatic membership. In my view, Scotland will need to apply afresh for membership of the EU.

Regarding membership of NATO, this would be effected if Scotland fulfils all the conditions set out in the membership action plan (MAP) as agreed by Scotland and NATO. The MAP would cover political, economic, defence, military and security, as well as legal issues concerning its membership. Although a NATO member state is subject to the obligations of the Treaty, including its Strategic Concept, which defines NATO as a nuclear alliance, there is some flexibility as to how a state participates in the Alliance, and that might assist in solving the question concerning the stationing of nuclear weapons on Scottish territory.

“The World Trade Organisation is the main international organisation which deals with trade issues. It consists of states and it has also a dispute settlement mechanism”

The European Free Trade Association (Norway, Iceland, Switzerland, Liechtenstein) is another organisation that Scotland might wish to join if EU membership somehow stalled. The EFTA Convention regulates free trade among member states. EFTA is an intergovernmental organisation, in contrast to the EU which has supranational characteristics in certain areas. The EEA (European Economic Area) Agreement between the EU and EFTA extends the internal market of the EU to EFTA member states.

Human rights: how far?

An independent Scotland should also become party to human rights treaties. This would provide proof of good international citizenship, as well as of Scotland’s commitment to protecting and promoting human rights at home and abroad.

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) is the main instrument for the protection of human rights in Europe. Becoming party to the ECHR depends on membership of the Council of Europe (CoE). However, the ECHR may continue to apply uninterrupted following a declaration of independence and before Scotland became party to the CoE/ECHR, unless Scotland declared otherwise.

There are 14 Protocols additional to the ECHR to which Scotland should become party. As party to the ECHR, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) would have automatic jurisdiction to entertain individual as well as inter-state complaints concerning possible violations of the ECHR by Scotland. Scotland could also bring cases before the ECtHR against other states.

“The law of the sea regulates a number of maritime areas and provides for the rights and duties of states over these areas”

In addition to the ECHR, there are many other international or regional, general or specialised human rights instruments to which Scotland should become party. What it is important to stress is that although joining international human rights treaties is important for the protection of human rights, it is even more important for the effective protection of human rights to grant individuals the right to petition international human rights bodies. As party to the ECHR, Scotland would automatically recognise the right of individual petition, but this right is discretionary as far as other conventions are concerned. For example, the UK is not a party to the Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, or the Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, which recognise the right of individual petition. Scotland would show its commitment to human rights by ratifying these protocols.

Concerning the question of whether the ECHR or other human rights treaties would apply directly within Scotland or would need to be incorporated into domestic law, it all depends on how the Scottish constitution would deal with the relationship between international and domestic law. In case international law instruments needed to be incorporated, Scotland should enact legislation similar to the Human Rights Act in order to incorporate the ECHR.

Maritime matters

Another area of interest to Scotland would be the law of the sea. The law of the sea is codified in the four Geneva Conventions of 1958 (Territorial Sea, High Seas, Fishing and Conservation of the Living Resources, and Continental Shelf), and in the 1982 Convention on the Law of the Sea which superseded these Conventions. Many rules found in the aforementioned Conventions are also customary rules.

The law of the sea regulates a number of maritime areas and provides for the rights and duties of states over these areas. It also contains rules on maritime delimitation which will be of critical importance to Scotland, due to North Sea oil.

This issue has been discussed in this Journal (Livingstone, “Independence before the law”, Journal, December 2012, 10), but it should be stressed that maritime delimitation is not exclusively a legal question but has geographical, geological, economic and political dimensions as well. Without going into specific rules, the principles that define maritime delimitation are that (i) no unilateral delimitations should take place, and (ii) delimitation should be effectuated on the basis of equitable criteria. Scotland may delimit its maritime zones through agreement, submit the issue to arbitration, or submit it to a court, for example the International Court of Justice or the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea.

Other roles

Scotland should also become party to the International Criminal Court (ICC). The ICC would exercise jurisdiction over the crime of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and the crime of aggression only if Scotland was unable or unwilling to exercise its jurisdiction over these crimes. On ratification, Scotland should declare whether the ICC would have ratione temporis jurisdiction from the date Scotland acceded, or from 1 July 2002, which is the date that the Rome Statute entered into force. Also, with regard to the crime of aggression, Scotland should declare whether it accepted the jurisdiction of the ICC for that crime.

Scotland should also become a member of international economic organisations. One of them is the International Labour Organisation. There are in total 396 conventions, protocols, and recommendations which Scotland should ratify. The International Monetary Fund is another organisation whose aim is global monetary co-operation and stability. The Board of Governors is its highest decision-making body, consisting of country representatives. Voting shares are based on quotas. The World Bank is an organisation whose mandate is to provide financial and technical assistance to developing countries. The World Trade Organisation is the main international organisation which deals with trade issues. It consists of states and it has also a dispute settlement mechanism.

Context

The preceding paragraphs offer a concise overview of the international law context within which an independent Scotland would operate. It should be stressed that international law empowers but also constrains state action. An independent Scotland would need to accept this dual function of international law, and avoid overoptimistic or overpessimistic attitudes towards international law. It would also need to be cognisant of the fact that international law is one parameter in moulding state relations, with politics being another important parameter.

In this issue

- Risk and the duty to inform

- Decrofting back on track

- The long road to qualify

- Scotland scores on “Themis” debut

- Equality and regulatory reform

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion column: Martin Crewe

- Book reviews

- Profile

- President's column

- What right of way?

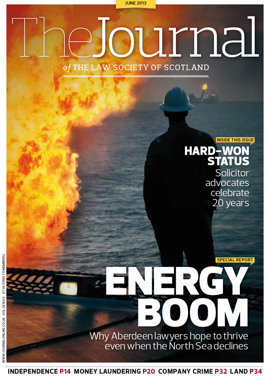

- Gas in the tank

- Scotland on the world stage

- Up there with the best

- The Significant Seven

- Out on 65?

- Gatekeeping the experts

- Fairway failings

- Beware of solvent liquidations

- Passing off update

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Holyrood out of bounds

- DPAs: cross-border confusion?

- The road to land reform, but where is it going?

- How not to win business: a guide for professionals

- Information security: raising the bar

- Waste: help sort it out

- Where there's a will

- Ask Ash

- "Reply to all"

- Law reform roundup

- Incidental financial business: amendments ahead

- Times are tough