The long road to qualify

Obtaining a training contract with a law firm is, perhaps, more difficult than it has ever been. Not since the abolition of scale fees in the mid-1980s has there been so much hysteria about the state of the legal profession. Ask any criminal lawyer today about legal aid, and some may shrug their shoulders and mutter something about it being “gone and never coming back”. Not even the “big firms” are safe. Consider Semple Fraser’s misfortune in March 2013, with Dundas & Wilson and others stepping in to assist. For anyone currently considering taking those first few tentative steps into the profession, there may be some serious doubts harboured about “doing the right thing”.

There is a checklist. LLB, check. Diploma, check. Work experience, check. Previous degree a bonus – check. So what is it that employers want? Well, careers advisers at university drone on and on about being a well rounded person. And practitioners, quite rightly, want a trainee who can produce the goods from the word go. So I took heed of the advice given when I was on my Diploma at Glasgow and went looking to see what I could find. Some “outside-of-the-box” thinking in due course led me to the door of a Wiltshire based charity called The Leap Overseas Ltd.

After some browsing and a few phone calls, I had signed up to a law internship which combined some volunteering activities. I was sent itineraries of the projects I’d be working on and, more importantly, the law firms whose door I would darken: Star Attorneys, and Law Access Advocates. This sounded promising.

Two strands of work

My destination was Arusha, a small city of 300,000 inhabitants in the East African country of Tanzania. The group I found myself in was one of English 19-year-olds who had embarked on a gap year before heading off to university. The firms were civil firms. Ideal, I thought, as my experience at home had been predominantly criminal work.

My time in Tanzania was split into two parts, legal work experience and helping with community projects.

The raison d’être of the trip was the law placements. From the outset I must make it clear that the experience gained of actual substantive law was not massive. For example, around 35% of any evidential material, such as newspapers or even client correspondence, was in Swahili. The remainder was in English and the legal system itself was largely borrowed from English law. Indeed on many occasions, House of Lords cases were a very persuasive precedent. Phraseology such as “plaintiff” and “defendant” was a feature. The Tanzanian Law Reports read like a Scots Law Times.

The volunteering projects were varied, but were broadly centered on carrying out aid work in various schools. I shovelled cement. I laid bricks. I installed panes of glass in windows. Most remarkably, I was genuinely amazed at the sense of making do with what few resources were available. Such scant availability of materials (which had been paid for by my fellow volunteers and me) really did lead to some phenomenal teamwork. For example, sand had to be carried in plastic buckets uphill. Going the whole way exhausted everyone. So, we put our heads together and formed a chain the length of the hill. A continuous supply of sand and happy, energetic volunteers ensued.

My supervisor at Star Attorneys, Mr Aikida, gave me and the two other law interns some live cases to read. He was aware that I had completed my legal studies. In a tongue-in-cheek manner he asked me to give a précis of my thoughts on the case. I read all the precedents and considered the evidence. He represented the plaintiffs in a representative suit against the local authority. His clients were the descendants of a travelling community who had occupied their land “openly, peaceably and without judicial interruption” for 80 years. The defendants wished to destroy their homes to construct a new Chinese-built highway, but without the courtesy of compensation required under the Roads Act (Tanzania) 2007. Under the local limitation laws, the magic number was 12 years. The case continues.

Realities of life

Perhaps the most interesting part of the time in Star was the way that a Tanzanian law firm is run. Power shortages in the Third World are common. Rolling blackouts are a feature of everyday life in Tanzania. But the lawyers work in the dark on battery-powered laptops without so much as a twitch when the plugs stop working.

Itching for some court experience, we asked Mr Aikida for a trip to court. He was unfortunately too busy, so we headed over to the International Criminal Tribunals of Rwanda. It being almost 20 years since the first proceedings began into the atrocious genocide, the courts were quiet. Instead of witnessing the advocates at first hand, I was led to a library to watch some cases on video. However, it was still remarkable to consider that this dark year in African history is still being played out in appeals to this day.

The conclusion of my time was served in Law Access Advocates. Some days there would be little to do, which was disappointing. The highlight was a Friday morning attendance at the resident magistrate’s court. The court itself was little more than a largish office where the resident magistrate sat like a stern headmaster while the advocates meekly presented their preliminary pleas, whilst sitting. Far removed, then, from the confident, eye-contact-filled advocacy which is required to do well on the Diploma in Legal Practice, never mind the Court of Session. Rather perplexingly, both sides of the adversarial procedure sit aside each other on a long wooden bench.

There were some similarities. Agents bowed as they entered the court – respect for the bench is universal. Agents for both parties spoke hurriedly to each other before proceedings, eager to eke out any advantage while trying furiously to avoid wasting time in court. But there were no wigs or even gowns. The clerk’s office was more akin to Rumpole of the Bailey, shelves groaning under the weight of dusty folders. And my mentor, a young woman who had qualified only last year, had already represented clients in murder trials in the High Court of Tanzania.

She was rather amazed when I told her that there are two branches of the Scottish legal profession. Her title was advocate – her role not too dissimilar to a solicitor advocate. But it was strange that an NQ was charged with protecting the rights of an alleged killer. Unsurprisingly, her firm Law Access – a multi-discipline practice – tended to shy away from criminal work. Appearances in High Court criminal trials are more valuable to the advocates’ status than for any pecuniary gain.

Long term value?

Realistically, the trip was not as legally labour intensive as six weeks with Shepherd and Wedderburn. Nor is any criminal advocate in Scotland is expected to represent a client who will face the death penalty for murder. Pinsent Masons do not have rolling blackouts. It would be legitimate to wonder what the value of a trip to another jurisdiction is. Perhaps it was the camel ride through a Maasai market, or maybe the day I slaughtered a goat for dinner, or, quite simply, that it is invaluable to take a step back to look at your own jurisdiction through the eyes of another. And there’s something to “name a time when” in interviews.

In this issue

- Risk and the duty to inform

- Decrofting back on track

- The long road to qualify

- Scotland scores on “Themis” debut

- Equality and regulatory reform

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion column: Martin Crewe

- Book reviews

- Profile

- President's column

- What right of way?

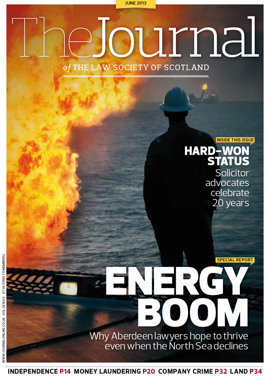

- Gas in the tank

- Scotland on the world stage

- Up there with the best

- The Significant Seven

- Out on 65?

- Gatekeeping the experts

- Fairway failings

- Beware of solvent liquidations

- Passing off update

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Holyrood out of bounds

- DPAs: cross-border confusion?

- The road to land reform, but where is it going?

- How not to win business: a guide for professionals

- Information security: raising the bar

- Waste: help sort it out

- Where there's a will

- Ask Ash

- "Reply to all"

- Law reform roundup

- Incidental financial business: amendments ahead

- Times are tough