Family business musings

Next to tax, the treatment of family businesses in divorce or dissolution actions is one of the most complex financial issues facing family practitioners. From the inevitable valuation issues to questions of liquidity and resources, we need to be alive to a number of opportunities and, indeed, issues possibly facing our clients. Choosing a seasoned, considered forensic accountant/valuer is fundamental to a solid platform for launching or defending a financial claim, whether it relates to a partnership or corporate entity.

Partnership business

When divorcing spouses or civil partners are also business partners, their interests in the business and in the divorce or dissolution action are often irreconcilable. Instances often arise of a race to the finish line where one party has an interest in seeking partnership remedies (for example count, reckoning and payment following a partner’s resignation), whereas the other will potentially derive greater benefit from having matters dealt with in the context of divorce or dissolution (for example, by advancing special circumstances arguments in respect of the partnership). The opportunity to right a perceived wrong arising from the outcome of the partnership remedy will not always be available in the context of a divorce action.

Will a client be in a stronger position by invoking partnership remedies or family proceedings? The timing of the resignation of a partner or dissolution of the partnership may have a significant impact on the sums due under the partnership agreement. Attempts to interdict the other party from ending a partnership in order to defeat, in whole or part, a party’s claims on divorce, are unlikely to be successful (Robertson v Robertson 2009 Fam LR 13).

The court has limited powers to regulate what should happen to an ongoing partnership where the partners are divorcing spouses or civil partners. What about the interests of partnership creditors? What of tax liabilities? What of the bank, to whom the partners may have personal liability for unsecured borrowings? Transfers of partnership interests rely on information from the partners, and advising clients to seek such a transfer, while generally accepted to be competent, may deliver a hornets’ nest of personal liability: beware of doing so without due diligence. Clearly, issues arise as to what actually is being transferred when both real and personal rights exist. Partnerships can present significant challenges in divorce and dissolution, and a solid overview of partnership law is critical before seeking any transfer.

Assets converting to matrimonial

It is not unusual for family businesses to be generational and for one party to hold their interest in the business prior to the marriage. Issues often arise from changes to a business over the course of the marriage, and it is not unusual to advise clients on the effect that corporate restructuring has on the matrimonial pot.

Business lenders have been known to insist that a small company increase its share issue as a prerequisite of providing finance. Such additional shares are deemed acquired during the marriage and as such are matrimonial property (Whittome v Whittome 1994 SLT 114; Latter v Latter 1990 SLT 805). A new partnership agreement entered into during the marriage does not automatically make the partnership interest matrimonial, even if the new agreement affects the rights of the partners, or increases their beneficial interest.

We increasingly see cases where a party is gifted shares during the marriage. By the relevant date, those shares may hold very significant value owing to the enterprise of that party. All too often that value is out of reach of the other spouse on divorce except in limited circumstances, most usually where there has been a restructuring of the company significant enough to render the share issue matrimonial property. A further complication arises where it is recognised that a restructure renders the party’s shareholding matrimonial, but it is argued that, in real terms, the beneficial interest or underlying business assets are unchanged and so the shareholding should not form part of the matrimonial pot.

The assets acquired by a business over the course of a marriage are not matrimonial property (where that business is set up and run as a legitimate business and the shareholding is not matrimonial property: Wilson v Wilson 1998 SCLR 1103), but this does not preclude a s 9(1)(b) argument to take account of the other party’s contributions to the enterprise. Does this go far enough to justify fairness?

In recent years the courts have seen cases which are increasingly seeking to challenge the statutory boundaries and the principle of fairness. We do need to challenge our assumptions on these matters and, cost allowing, be more willing to look behind businesses to establish whether or not there is scope to challenge the stricter limitations of the statute and to consider a client’s circumstances more readily on what is “fair”.

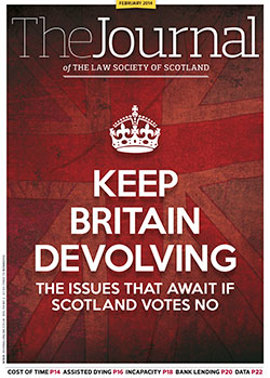

In this issue

- Cold case examination of early childhood evidence

- Incentivising employee ownership

- The diversity imperative

- Towards a more inclusive democracy

- Journal magazine Index 2013

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion: Campbell Read

- Book reviews

- Profile

- President's column

- RoS's services for solicitors

- Issues for the Union

- Critical mass

- Is this where it ends?

- Testing capacity

- Making plans for auto-enrolment

- Loosening the purse strings

- Data: don't be caught out

- Punished enough?

- Prior statements practice

- Family business musings

- TUPE: armour not gold-plated?

- Pension policy - a vote winner?

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- In with the system

- Check and double-check

- Lender Exchange ahead

- Have you the capital?

- How not to win business: a guide for professionals

- Reflections from the Complaints Commission

- Ask Ash

- Danger spots

- It's the name of the game

- Law reform roundup

- Conference aspires to judicial diversity