Towards a more inclusive democracy

Background: discrimination of social rights

In an age when human rights are deemed as the cornerstone of our civilization, democracy, citizenship, and the guardian of our individual freedoms, the general consensus for many years amongst the majority of scholars (such as J S Mill(1), Isaiah Berlin(2) and F A von Hayek(3)) and politicians alike (most notably, Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan) has been that these ideals can be achieved simply through the promotion, implementation and safeguarding of civil and political rights. In so doing, they have not only drawn a distinction between civil and political rights and socio-economic rights, but have also elevated the former to a higher status than their counterparts.

This was reflected in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights which, although it recognised and endorsed social rights(4) alongside civil and political rights, was split into a two-tier system of rights. This led to the birth, in 1966, of two separate treaties: the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (“ICCPR”)(5) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (“ICESCR”)(6), with the former enjoying supremacy of status and priority in implementation and protection of its provisions(7).

The role of social rights

The underlying cause of disparity between the protection of civil and political rights and socio-economic rights seemingly emanates from a long held misconception about the role of socio-economic rights. The idea that socio-economic rights should be accorded inferiority of status to civil and political rights – because of the latter’s apparent inherent negative nature – is not only misguided, but also self-defeating and counter-intuitive. Socio-economic rights are not only complementary partners of civil and political rights, but a requisite precondition to the fulfillment of the latter(8). At the risk of oversimplification, it can be asserted that civil and political rights have inherent socio-economic components, and that “enjoyment of civil and political rights is rendered meaningless if social rights are neglected”(9).

Indeed, discussing the justification for a greater degree of social rights, Justice Waldron reached a very similar conclusion when he stated: “If one is really concerned to secure civil and political liberty for a person, that commitment should be accompanied by a further concern about the conditions of the person’s life that make it possible for him to enjoy and exercise that liberty”(10), and that having freedom without the necessary material to be able to exercise it is no freedom(11). It therefore follows that if social rights are a necessary prerequisite for the realisation of civil and political rights, they (social rights) should be given equal weight and relevance whenever a conflict between civil and political, and socio-economic, rights arises. In doing so, we can promote and solidify the position of civil and political rights as fundamental rights to all.

Indivisibility of human rights

On a closer analysis of the relationship of civil and political rights, on the one hand, and socio-economic rights, on the other, it becomes clear that the relationship between the two sets of rights is one of “bidirectional support”(12). That is to say, there exists a symbiotic relationship between the two sets of rights, whereby one contributes to the functioning and stability of the other. Accordingly, the substantive integrity of civil and political rights would greatly diminish if the provision of basic socio-economic rights were to be neglected. This will lead to further corrosion of socio-economic rights, as the less well off in society would find themselves adrift of the political and democratic cycle(13), the arena which affords them equality of status. And the vicious cycle will continue. Those living in suburban Cape Town in makeshift houses, with lack of food and drinking water, or those living in the slums of New Delhi, or those living in the surrounding villages of Rio de Janeiro – places where socio-economic rights are enshrined in the constitutional order but where delivery of such provisions has proved elusive and bordering on constitutional deception – are cases in point. Therefore, if socio-economic rights are necessary for the protection of civil and political rights, it must follow that socio-economic rights must be necessary for the protection and fostering of democracy too, since the latter cannot be upheld without the exercise of civil and political rights.

Social rights and democracy

Although there are various types of democracies, a basic definition would entail that the decision of the majority would be legitimate, if it is a majority in a society of equals(14). However, there are two contemporary models of democracy which place particular emphasis on the significance of participation by the citizens in the political process. First, deliberative democracy holds that, for the decision making to be legitimate, it must be preceded by authentic deliberation and not mere voting. Secondly, participatory democracy strives to create opportunities for all members of society to contribute to the decision making and seeks to broaden the range of people who have access to such opportunities.

For the best model of democracy to function properly requires a limit on the scope of social inequality and poverty amongst citizens of any society. Poverty, chronic joblessness, lack of education, lack of basic health care, and the social exclusion and sense of indignity that accompany the aforementioned ills, restrict people who find themselves in that state from participating on anything like a roughly equal footing in the political community or in the world of work and opportunity(15).

Without basic social provisions, those in poverty will feel alienated in their own society, feel that they have no stake in that society and therefore will be reluctant to vote. This does little to improve their plight as far as democracy is concerned, for if they do not take part in elections, their interests are less likely to be represented in the political sphere(16), and so the vicious cycle will carry on(17). Therefore, it follows that the lesser the scope and intensity of civic participation, the weaker the reasons for considering the final outcome of a deliberative (democratic) process impartial(18).

Social rights, therefore, are not complementary partners to the concept of democracy, but purport to act as a catalyst in the process which results in proper democracy. That is to say, one of the most prominent objectives upon which the progress towards democracy rests, is the “expansion of citizen’s rights (beginning with social rights)”(19), without which not only will the progress of democracy be halted, but its process will be destabilised by the forces of friction between the rich and the poor(20). Furthermore, for a democracy to flourish, it needs not only the casting of votes by its citizens, but also active participation in decision making which has been “part of democratic theory from Athens to nineteenth century England”(21). Indeed, Jean-Jacques Rousseau stated that by “actively participating in the laws which govern us, we remain free, in the sense that we are not subject to the commands of others but only to the rules that we have collectively created”(22).

Therefore, even if we assume that those suffering from poverty can manage to cast a vote in the elections despite the challenges they face, as discussed above, it is inconceivable to suggest that a person who is completely unsure about the prospects of food and shelter in the coming hours and days for himself and his family would be able to participate in a material sense in the political process, for that person will be worried sick and obsessed with the fact that he is hungry and homeless to such an extent that will leave no scope for reflection and deliberation about anything beyond his most pressing and urgent need. The only way the barriers to active citizen participation in the democratic process can be eradicated, is by meeting certain economic and social preconditions.

The role of courts in protecting social rights

There seems to be a great deal of cynicism about the role of courts in protecting social rights, for it raises questions about the legitimacy of judges overriding the decisions of democratically elected representatives of the population. However, as discussed above, social rights are needed to secure the equal value of political rights, enabling marginalised groups to “effectively fight for social transformation in other arenas”(23).

Furthermore, the proper role of the courts should be examined in the context of the wider political structure: what channels there are to address such concerns, whether they provide effective remedy, and the opportunities available to the marginalised groups to have their concerns addressed. The argument that judges should stringently defer to the politicians’ assessment of what social rights are to be provided is vacuous. In a democratic system, judges have a duty to protect all citizens’ rights and to ensure that “collective decisions are made by the political institutions, whose structure, composition and practices treat all members of the community, as individuals with equal concern and respect”(24). The courts’ role in this context is not to overrule the legislature, but to simply repair the malfunctioning of the democratic system when the latter “systematically impairs the interests of marginalised groups”(25). To this end, far from acting as an impediment to democracy, judicial activism in protecting social rights would make the democratic system healthier and more inclusive.

Furthermore, economic and social rights are incorporated in the legal framework of most countries, either in the national constitution such as the South African constitution, or in the form of human rights provisions in customary international law and legally binding treaties such as the European Social Charter or the ICESCR. Therefore in this context, it could be argued that social right litigation and judicial activism in order to alleviate the hurdles facing the poor and marginalised in their quest for the realisation of their civil and political rights is mandated by the will of the people as enshrined in the basic norms defining the terms of their community.

Since the promotion and protection of social rights enables disadvantaged citizens to exercise their political rights in a substantive sense (for example, people who are educated and lifted out of poverty will be more likely to participate in the political process as they will have both the intellectual and the material capacity which will allow them to do so), this process could foster greater active participation in the political process by the poor and marginalised, which in turn will help the system become more democratic.

Conclusion

Social rights and civil and political rights are two sides of the same coin; the latter could not be exercised in a substantive way without the fulfilment of the former. In the same manner, the exercise of civil and political rights is necessary for a democracy to function properly. As such, without the provision and protection of basic social rights, civil and political rights would become an item of luxury, only available to the affluent. That in turn could have consequences for democracy, as those who lack the material wealth to be able to exercise their political rights would find themselves isolated from their society and the political system, leading to a lack of participation by sizeable proportions of society, which in turn will compromise democracy.

References

(1) J S Mill and John Gray, On Liberty and Other Essays (Oxford World’s Classics, 1998).

(2) Isaiah Berlin, “Two Concepts of Liberty”, in Four Essays on Liberty (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1969).

(3) F A von Hayek, The Road to Serfdom (Routledge Classics, 2001; first published 1944).

(4) UDHR, articles 22-26.

(5) International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (adopted 16 December 1966, entered into force 23 March 1976): 999 UNTS 171.

(6) International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (adopted 16 December 1966, entered into force 3 January 1976) 993 UNTS 3.

(7) Article 2(1). Also see The Limburg Principles on the Implementation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, UN Doc E/CN.4/1987/17 (annex, reprinted in (1987) 9 Human Rights Quarterly 122).

(8) D Barak-Erez and A M Gross, Exploring Social Rights: Between Theory and Practice (Hart Publishing Ltd, 2007).

(9) Virginia Mantouvalou, “Work and Private Life: Sidabras and Dziautas v Lithuania”, European Law Review (2005).

(10) Jeremy Waldron, “Two Sides of the Same Coin”, in Liberal Rights, Collected Papers 1981-1991 (Cambridge University Press, 1993).

(11) G A Cohen, “Freedom and Money”, available at http://www.howardism.org/appendix/Cohen.pdf.

(12) J Nickel, “Rethinking Indivisibility: Towards a Theory of Supporting Relations Between Human Rights” (2008) 30 Human Rights Quarterly 984.

(13) Craig Scott, “Reaching Beyond (Without Abandoning) the Category of 'Economic, Social and Cultural Rights'” (1999) 21 Human Rights Quarterly 633, 645.

(14) R Dworkin, A Bill of Rights for Britain (London, Chatto & Windus, 1990).

(15) For a discussion of basic social rights’ role in the US constitutional democracy, see W E Forbath, Social Rights, Courts and Constitutional Democracy: Poverty and Welfare Rights in the United States, University of Texas School of Law, Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper no 81.

(16) J Carens, “Live-in Domestics, Seasonal Workers and Others Hard to Locate on the Map of Democracy” (2008) 16 Journal of Political Philosophy 419.

(17) Examining the American system, R Gargarella states that entrusting the property owners of society with protecting the national interest will lead to the protection of the property owning class only: “The Threat of Constitutionalism: Constitutionalism, Rights and Democracy”, available at www.law.yale.edu/Gargarella_The_Threats_of_Constitutionalism

(18) Carlas Santiago Nino, The Ethics of Human Rights (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991).

(19) For a discussion of conditions necessary for democracy, see European Union Preparatory Acts, Opinion of the Economic and Social Committee on Relations Between the European Union and Albania, OJ 1995, c236165.

(20) D Bilchitz, “Political Philosophy in Action: Developing the Minimum Core Approach to Socio-Economic Rights”, in Poverty and Fundamental Rights: The Justification and Enforcement of Socio-Economic Rights (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

(21) David Held, Models of Democracy (2nd ed) (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996).

(22) Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Social Contract (trans. Maurice Cranston) (London: Penguin Books, 1968).

(23) R Gargarella, “Courts and Social Transformation: An Analytical Framework”, in Gargarella, Domingo, Roux (eds), Courts and Social Transformation in New Democracies (Aldershot, Ashgate, 2006).

(24) R Dworkin, Freedom’s Law: The Moral Reading of the American Constitution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996).

(25) John Hart Ely, Democracy and Distrust: A Theory of Judicial Review (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1980).

Other reading

Virginia Mantouvalou, The Case for Social Rights in Debating Social Rights, April 2010, Georgetown Public Law Research Paper no 10-18.

Krzysztof Drzewicki, Catarina Krause and Allan Rosas, Social Rights as Human Rights, A European Challenge, Abo Akademi University (1994).

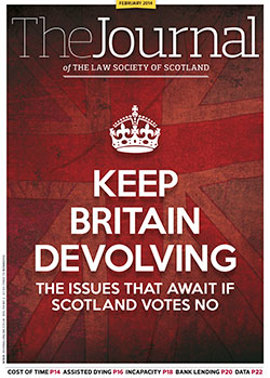

In this issue

- Cold case examination of early childhood evidence

- Incentivising employee ownership

- The diversity imperative

- Towards a more inclusive democracy

- Journal magazine Index 2013

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion: Campbell Read

- Book reviews

- Profile

- President's column

- RoS's services for solicitors

- Issues for the Union

- Critical mass

- Is this where it ends?

- Testing capacity

- Making plans for auto-enrolment

- Loosening the purse strings

- Data: don't be caught out

- Punished enough?

- Prior statements practice

- Family business musings

- TUPE: armour not gold-plated?

- Pension policy - a vote winner?

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- In with the system

- Check and double-check

- Lender Exchange ahead

- Have you the capital?

- How not to win business: a guide for professionals

- Reflections from the Complaints Commission

- Ask Ash

- Danger spots

- It's the name of the game

- Law reform roundup

- Conference aspires to judicial diversity