Actionable data wrongs?

A recent English High Court decision could have a significant impact on the future of privacy and data protection litigation. Vidal-Hall v Google Inc [2014] EWHC 13 (QB) confirms that “misuse of private information” is a distinct cause of action in tort. In addition, it opens the door to compensation claims for breaches of the Data Protection Act 1998 (“DPA”), even where no financial loss has been suffered.

The case concerns personalised online adverts. Google uses the browsing history of web users to sell advertising. Specifically, it uses “cookies” to track which websites are viewed by individuals. This allows its advertisers to target adverts directly to web users, based on their interests as ascertained from their browsing history. Information that a browsing history can reveal includes everything from shopping habits to more personal information such as hobbies, political affiliations, sexuality and religious beliefs. The targeted adverts which appear are generated from this information, and may therefore reveal personal information about the web user to any third party using that person’s computer.

Actionable wrong?

The claimants, UK-based web users, complain that Google (1) acted in breach of confidence, (2) misused their personal information, and (3) breached the DPA by collating such information from Apple’s Safari browser, without their knowledge or consent. They alleged that they had, as a result, suffered “acute stress and anxiety”, although they did not claim for any financial loss.

In terms of the English Civil Procedure Rules, claims can only be served on companies outside England under certain circumstances and with permission from the court. Google, which is domiciled in California, challenged the decision to permit service. The judgment discusses these service issues in detail.

However, in order to reach its decision on these issues, the court considered two issues of broader significance. These were: (a) whether any of the claimed wrongs were torts; and (b) whether there had been “damage” sustained, for the purposes of the DPA claim, in circumstances where no economic loss was alleged.

Recognised claims

The court followed an established line of authority and held that the claim for breach of confidence is not a tort in English law. Rather, it is an equitable concept.

As regards “misuse of private information”, the court reviewed the authorities to determine whether this was a type of breach of confidence case, or a separate tort in its own right. It concluded that the authorities, including OBG Ltd v Allan [2007] UKHL 21, suggested that although at one stage misuse of private information was seen as a type of breach of confidence claim, it is now better identified as a distinct tort.

The court accepted that the web users’ browsing histories may be personal data, as the users were potentially identifiable from that data. Thus, they had potential claims against Google for breach of the DPA.

Section 13 of the DPA provides that an individual, who has suffered distress as a result of breach of the DPA, is entitled to compensation only if he or she has also suffered damage.

Previously, it had been understood that s 13 could only compensate individuals for distress where pecuniary damage could also be shown. However, the court accepted a submission that damage could include “moral damage”, a recognised EU concept connoting the right to compensation for breach of individual rights, whether or not the loss is pecuniary. The court did not make a final decision on this controversial issue, but indicated that its preliminary view was that s 13 damage should include non-pecuniary damage.

Significance for Scotland

The judgment is significant for a number of reasons.

First, it clarifies that “misuse of private information” is a tort separate to breach of confidence. To date, there has been no Scots case law on the proper clarification of breach of confidence, i.e. whether it is a delict or a sui generis obligation, or on the Scots law relationship between breach of confidence and “misuse of private information”. However, commentators consider that the Scottish courts are likely to follow the English authorities on misuse of private information (see, for example Thomson, Delict, para 12.62), so this development is likely to be equally important to Scots practitioners. The separation of the law on breach of confidence and misuse of private information may allow the latter to develop in a direction separate to breach of confidentiality, and could hasten its future transformation into a general cause of action for “breach of privacy”.

In addition, the finding that financial loss may not be required in order to take an action for damages under s 13 DPA is significant. If, at the full hearing, the court decides that financial loss is no longer required, an increase in data protection cases on both sides of the border is likely.

In this issue

- The role of "attachment" in child custody and contact cases

- No protocol – what expenses?

- Ecocide: a worthy "fifth crime against peace"?

- Mandatory mediation: better for children

- Reservoir safety regulation: a changing landscape

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion: Mark Hordern

- Book reviews

- Profile

- President's column

- Digital deeds move closer

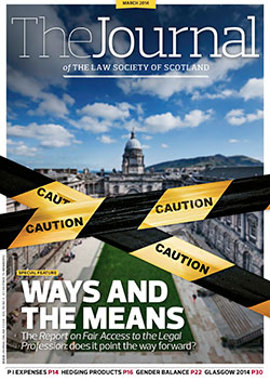

- Fair access - a fair way to go

- No protocol – what expenses? (1)

- Hedges: not all bad news

- Daring to be different

- Financial planning or wealth management – is there a difference?

- Success in the balance

- Wealth management for business leaders and owners

- Purpose of the protocol

- Actionable data wrongs?

- Land Court: business as usual

- Penalty points

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Fever pitch

- Heritage regained

- All grist to the mill

- Wills: is it OK to act?

- Gongs, dinners and just deserts

- Perils of the home

- Ask Ash

- Scots lawyers debate Union in London

- Public Guardian news roundup

- Law reform roundup

- Personal Injury User Group at your service

- Diary of an innocent in-houser