Heritage regained

Since 1986 there has been uncertainty as to a Scottish liquidator’s right to disclaim. Although explicit statutory authority is given for an English liquidator’s right to disclaim onerous property, no such right exists for their Scottish counterparts. While some believed a Scottish liquidator could have a common law right to disclaim, the matter had never been tested.

As previously reported (“Heritage Disowned”, Journal, September 2013, 32), the Outer House recognised the competence of a liquidator abandoning a company’s interest in heritable property in the matter of the liquidation of Scottish Coal Co Ltd: [2013] CSOH 120. This decision has been reversed by the Inner House on appeal: [2013] CSIH 108.

In reversing the Outer House decision, the court set out in detail its position on a Scottish liquidator’s right to disclaim onerous property. While this gives more certainty, the position is still unsatisfactory and raises as many questions as it answers. For example, it is unclear exactly how the costs of complying with environmental permit terms are to be classed in a Scottish liquidation, and also how the concept of a disclaimer in accounting terms (as would apply to the disclaimer of Scottish property by an English liquidator) interacts with practical matters such as occupier’s liability. Practitioners therefore watch with interest to see whether this will be cleared up by further appeal, or whether another case dealing with these matters is brought. This article looks at the reasoning behind the Inner House’s decision.

Abandoning heritage

The Outer House decision was mainly based on its understanding that heritable property could be abandoned. The court considered that both the Crown’s ability to disclaim property that had become bona vacantia and a trustee in bankruptcy’s right to refuse to accept the vesting of a bankrupt’s property supported this proposition (the latter being relevant as a liquidator’s powers are by and large derived from those bestowed on a trustee in bankruptcy).

The Inner House disagreed that property could be abandoned. Instead the judges considered that ownership of property could only be terminated by virtue of a legal process (such as land attachment) or by way of voluntary process (for example, by disposition). Accordingly, ownership could not be abandoned, only transferred to another.

Applying this to the vesting of the estate of a bankrupt in a trustee, the Inner House’s view was that property only vests in the trustee to the extent of a personal right, and that actual title does not transfer except in certain limited circumstances. While the Outer House had been directed towards cases concerning a trustee’s right to “abandon” property, the Inner House’s view was that these demonstrated a trustee’s right to abandon their personal interest in property (as acquired by virtue of the vesting), rather than an abandonment of ownership itself. The trustee’s “abandonment” of the vesting leaves ownership of the land where it is, i.e. with the bankrupt.

Applying this to a liquidation, the property of an insolvent company does not vest in its liquidators. There is no personal right for a liquidator to abandon. As there is no concept of abandonment of a real right in property in Scotland, the Inner House’s view was that “in the absence of a specific power to do so, a liquidator (as agent of the company) has no power to divest the company of a real right in land by unilateral disclaimer whereby the land would become bona vacantia and fall to be administered by the Crown, if it elected to exercise the prerogative right” (opinion, para 122).

Consideration was given to the apparent disparity this created between the insolvency regimes in England and in Scotland (with an English liquidator’s right to disclaim onerous property both north and south of the border being established). The Inner House’s view was that it was not anomalous that an English liquidator could disclaim a property that a Scottish liquidator could not. However, the abandonment would apply from an accounting perspective only, with ownership of the land remaining with the insolvent company.

Environmental permits

The environmental permits that the liquidators of Scottish Coal sought to disclaim were licences under the Water Environment (Controlled Activities) (Scotland) Regulations 2011 (“CAR”). CAR regulates activities which may affect the water environment, and sets down a number of conditions that must be complied with by the “responsible person”. In the case of permits held by a company that becomes insolvent, CAR makes specific provision for any administrator, receiver or liquidator appointed to that company to be considered a “responsible person”. This means that the Scottish Coal liquidators became the “responsible person” in terms of the permits held by the company, and were required to comply with the conditions attaching to these permits at a cost of around £500,000 per month.

A fundamental factor in the Outer House’s decision that the permits could be disclaimed was the court’s understanding that the provisions of CAR making a liquidator a responsible person were outside the legislative competence of the Scottish Government. By requiring a liquidator to incur costs in complying with the permit terms, CAR effectively altered the law on expenses and preferred and preferential debts in liquidation, a reserved matter in terms of the Scotland Act 1998.

After reviewing the relevant legislation and associated case law, the Inner House came to the view that only matters that had as their purpose the amendment of a reserved matter would fall outside the legislative competence of the Scottish Government. In passing the terms of CAR, the Scottish Government sought to implement the terms of a European directive, the Water Framework Directive (2000/60/EC), requiring member states to ensure that land was left in a fit state when licensed works ceased. The purpose of CAR was therefore not to amend the insolvency regime. That it did so to any extent was incidental to its primary purpose. In any event, the Inner House was of the view that in requiring liquidators to comply with the provisions of the permits, CAR simply created another expense of the liquidation and did not alter the priority of claims law. Accordingly, CAR did not alter the law on reserved matters.

In the Inner House’s decision, much was made of CAR’s specific inclusion of liquidators as responsible persons and also the fact that CAR sets down a procedure for the responsible person to surrender a permit when a controlled activity ceases. It was held that this specific procedure and its application to all types of responsible person would take precedence over any other more general method for bringing the permit to an end, such as disclaimer by a liquidator.

In this issue

- The role of "attachment" in child custody and contact cases

- No protocol – what expenses?

- Ecocide: a worthy "fifth crime against peace"?

- Mandatory mediation: better for children

- Reservoir safety regulation: a changing landscape

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion: Mark Hordern

- Book reviews

- Profile

- President's column

- Digital deeds move closer

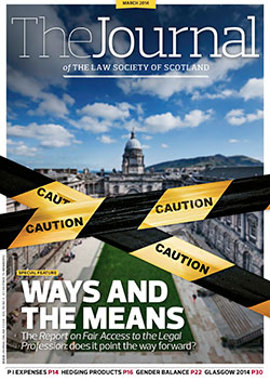

- Fair access - a fair way to go

- No protocol – what expenses? (1)

- Hedges: not all bad news

- Daring to be different

- Financial planning or wealth management – is there a difference?

- Success in the balance

- Wealth management for business leaders and owners

- Purpose of the protocol

- Actionable data wrongs?

- Land Court: business as usual

- Penalty points

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Fever pitch

- Heritage regained

- All grist to the mill

- Wills: is it OK to act?

- Gongs, dinners and just deserts

- Perils of the home

- Ask Ash

- Scots lawyers debate Union in London

- Public Guardian news roundup

- Law reform roundup

- Personal Injury User Group at your service

- Diary of an innocent in-houser