Directors: how much is too much, or not enough?

Duties and disqualification

The off-pitch troubles of what was Rangers Football Club plc are well documented, including the activities of the former (now disqualified, for a second time) director Craig Whyte. On this occasion, the order under the Company Directors Disqualification Act 1986 will last 15 years – the maximum available at present.

When a disqualification order is passed, for the period specified in the order, a person cannot (a) be a director of a company, act as receiver of a company’s property, or in any way, directly or indirectly, be concerned or take part in the promotion, formation or management of a company (or limited liability partnership); or (b) act as an insolvency practitioner. Breach of an order is a criminal offence, and the disqualified person can be held personally liable for the company’s debts incurred during the contravention.

This case is a helpful illustration that a breach of duty by a director can be an important factor in disqualification proceedings when ascertaining what conduct makes someone “unfit” to be concerned in the management of a company. In his opinion ([2014] CSOH 148; 30 September 2014), Lord Tyre made reference to Mr Whyte’s “reckless disregard for the interests of the company to which he owed fiduciary duties”, and “wilful breach of a director’s administrative duties”.

Overseas duties: not out of mind

In Group Seven Ltd v Allied Investment Corporation Ltd [2014] EWHC 2046 (Ch), the English High Court held that two directors (one was also general legal counsel) who had been taken in by a substantial fraud were in breach of their duties as directors to exercise reasonable skill and care, but were not in breach of their fiduciary duty. The case (decided under Maltese law) is interesting for several reasons, not least the purported involvement of the Illuminati, the Vatican and the Royal House of Aragon, to name a few, in the supposed investment. More pertinently, it emphasises that directors should act honestly and take care against becoming victims of fraud.

Behaviour like this could soon be referred to in future director disqualification applications, given BIS, the Department for Business, Innovation & Skills’ intention to provide the courts with extra powers to take into consideration overseas misconduct.

BIS made the suggestions via the Transparency and Trust consultation response paper, detailing more factors to take into account when considering an individual’s fitness to hold a UK company directorship. These now form part of the many changes put forward in the Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Bill. The bill proposes to amend the 1986 Act to include a range of additional matters to be taken into consideration, such as:

(1) The extent to which the person was responsible for the causes of any material contravention by a company or overseas company of any applicable legislative or other requirement.

(2) Where applicable, the extent to which the person was responsible for the causes of a company or overseas company becoming insolvent.

(3) The frequency of conduct of the person which falls within paragraph 1 or 2.

(4) The nature and extent of any loss or harm caused, or any potential loss or harm which could have been caused, by the person’s conduct in relation to a company or overseas company.

Duties to subsidiaries?

In Smithton Ltd v Naggar [2014] EWCA Civ 939, proceedings were brought against Naggar, a director of a holding company, by its former subsidiary, who alleged that Naggar was a de facto or shadow director and that he had breached fiduciary duties owed to the subsidiary. The court held that Naggar was not a de facto director, as although he admitted carrying out “directorial duties”, that was consistently in a different capacity to a director of the subsidiary. The case followed leading authorities in this area, but is useful in providing further guidance as to what constitute appropriate actions for a director of a holding company. For example, it helped Naggar to be able to point to a joint venture agreement which did not provide for him to be a director, the fact that he did not hold himself out to be a director of the subsidiary, and that he did not attend board meetings.

The bill was also briefly referred to, but in the form of “be careful what you wish for” (see para 25 in relation to the proposal to prevent the appointment of corporate directorships). Though directors of holding companies will be relieved by the decision, they should continue to be alert in order that any potential liability as a de facto director is minimised.

The latest proposals for change will make it easier for directors who have carried out misconduct, whether at home or abroad, to be disqualified.

Emma Arcari, associate, CCW Business Lawyers Ltd

In this issue

- Factors in the balance

- Balancing the right to decide

- Life yet in oil and gas

- Commercial awareness begins at trainee stage

- Relocation and the finances of contact

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion: Archie Maciver

- Book reviews

- Profile

- President's column

- Up and running at last

- People on the move

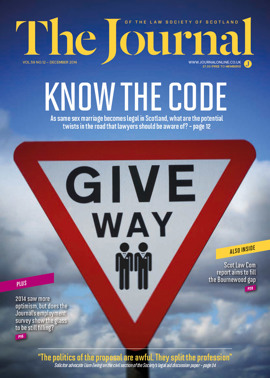

- With this Act, I thee wed

- Tax: a mission to inform

- For better, for worse

- Filling the Bournewood gap

- Power talking

- For whose aid?

- Balanced view

- A laughing matter?

- Directors: how much is too much, or not enough?

- Credit where it's due?

- New age, new image, new media, continuing problems?

- Scottish Solicitors Discipline Tribunal

- Lawyers as leaders

- Property Law Committee update

- Property Standardisation Group update

- Over the finishing line – 2

- Not proven no more?

- Vulnerable clients guidance now extended to the young

- From the Brussels office

- Take it to the schools

- A future – a vision

- Ask Ash

- A strategy with legs?

- Who's got what it takes?

- I can act, but should I?

- Prominence unplanned