Filling the Bournewood gap

Scotland urgently needs procedures to authorise what are otherwise unlawful deprivations of liberty, contrary to article 5 of the European Convention on Human Rights. The people affected are some hospital patients and some people in care homes, or in accommodation arranged by adult placement services, who lack capacity to give valid consent to the arrangements. Legislation is required to cover this, and has now been proposed in the Scottish Law Commission’s Report on Adults with Incapacity (No 240), published in October 2014.

That there is a significant gap in Scottish adult incapacity law has been apparent for a decade, since the decision of the European Court of Human Rights in HL v United Kingdom (2004) 40 EHRR 761, in which it was held that article 5 was contravened by the admission to a psychiatric hospital and continued residence there, without lawful process, of a person whose learning disability prevented him from validly consenting to those arrangements. “Bournewood gap” entered the language, from the name of the hospital.

Article 5(1) declares that “No one shall be deprived of his liberty save in the following cases and in accordance with a procedure prescribed by law”. One of those cases is “the lawful detention… of persons of unsound mind”. Under article 5(4): “Everyone who is deprived of his liberty by arrest or detention shall be entitled to take proceedings by which the lawfulness of his detention shall be decided speedily by a court and his release ordered if the detention is not lawful”; and under article 5(5): “Everyone who has been the victim of arrest or detention in contravention of the provisions of this Article shall have an enforceable right to compensation”.

Thus, in the recent case of DC before the Court of Session, unreported and now settled, a person sought liberation, and damages totalling £80,000 from a local authority and the operators of a care home for alleged deprivation of his liberty in respect of his placement in the care home, authorised neither by “a procedure prescribed by law” nor his own consent. That case raised several issues not now determined, including whether it could be competent for an attorney to authorise a deprivation of liberty.

The road to Cheshire West

England & Wales sought to bridge the Bournewood gap in the Mental Capacity Act 2005, as amended by the Mental Health Act 2007, by introducing the “DOLS” (deprivation of liberty safeguards) regime. This has been the object of increasing criticism as being complex, difficult to understand, and costly to operate. In P v Cheshire West and Cheshire Council; P and Q v Surrey County Council [2014] UKSC 19 (“Cheshire West”), Lady Hale described the DOLS safeguards as having the appearance of “bewildering complexity”.

Just a week before that decision was handed down, the Westminster Health Select Committee issued a report on its post-legislative scrutiny of the Mental Health Act 2007 containing the following criticism of the DOLS regime: “The safeguards are not well understood and are poorly implemented. Evidence suggested that thousands, if not tens of thousands, of individuals are being deprived of their liberty without the protection of the law, and therefore without the safeguards which Parliament intended. Worse still, far from being used to protect individuals and their rights, they are sometimes used to oppress individuals, and to force upon them decisions made by others without reference to the wishes and feelings of the person concerned. Even if implementation could be improved, the legislation itself is flawed.”

It is unsurprising that the Scottish Law Commission has not sought to replicate the DOLS regime in Scotland.

One of the difficulties of that regime is that it is tied to the article 5 definition of deprivation of liberty, thus requiring application of complex Strasbourg jurisprudence in every individual case. In HL, a substantial list of factors were held to have contributed to a finding of deprivation of liberty. Commendably, in Cheshire West Baroness Hale sought to cut through the complexities and offer an “acid test” that could be applied, namely to ask “whether the individual in question is subject to continuous supervision and control and is not free to leave”.

Cheshire West could reasonably be seen as putting an end to a trend towards trying to find inventive reasons for holding that particular situations did not amount to a deprivation of liberty and accordingly did not place further burdens on the DOLS regime. Such considerations included suggestions that in the case of persons with significant disabilities, the comparator should be with the situation of any other person with similar disabilities receiving necessary care; and that the benign reason and purpose of a particular regime, assessed objectively, could be influential. Cheshire West explicitly rejected both of those approaches.

In a key passage, Lady Hale said (para 45): “In my view, it is axiomatic that people with disabilities, both mental and physical, have the same human rights as the rest of the human race. It may be that those rights have sometimes to be limited or restricted because of their disabilities, but the starting point should be the same as that for everyone else. This flows inexorably from the universal character of human rights, founded on the inherent dignity of all human beings, and is confirmed in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities”.

DOLS out, SRoLs in

An immediate consequence of Cheshire West was a realisation that a substantial increase in DOLS applications would be necessary. The Court of Protection held a hearing on 5 and 6 June 2014 to address this. Evidence indicated that on the basis of 106 responses (out of 170) from local authorities in England, DOLS referrals from hospitals and care homes were expected to hit 93,900 in 2014-15, a rise from 10,050 in 2013-14, at an increased estimated cost of £70 million. Against that background, it is unsurprising that the Scottish Law Commission was obliged to have regard to the potential resource consequences of whatever regime it should propose, as well as difficulties over the definition of a deprivation of liberty.

On the latter point, rather than attempt to provide a clear and workable definition of “deprivation of liberty”, the draft bill annexed to the report would instead introduce, and clearly define, the concept of “significant restriction of liberty” (in this article, “SRoL”), which should catch all relevant situations of potential deprivation of liberty. Any other situations also caught would nevertheless merit the protections and procedures of the proposed new provisions.

Subject to exceptions, the draft bill provides that a SRoL would exist when any two of the following three criteria apply:

- An adult is not allowed to leave premises unaccompanied, or due to physical impairment is unable to leave unassisted.

- Barriers limit the adult to particular areas of the premises.

- The adult’s actions (within or outside the premises) are controlled by physical force, or by use of restraints, or by medication administered for that purpose. Specially designed clothing is explicitly included within “restraints”.

Excluded from the definition are “measures applicable to all residents to facilitate proper management of the premises, without disadvantaging residents excessively or unreasonably”, and devices for the sole purpose of preventing falling.

The provisions of the draft bill address: (1) Adults who are receiving medical treatment, or who are being assessed as to whether medical treatment is required, and who are incapable regarding decisions about going (or not going) out of hospital, or out of some part of a hospital (proposed new ss 50A-50C of the Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000). (2) Authorisation of SRoL in relation to placement, in a care home or in accommodation arranged by an adult placement service, by reason of vulnerability or need resulting from infirmity, ageing, illness, disability, mental disorder, or drug or alcohol dependency. (3) Authorisation of SRoL in relation to short-term care such as is described in (2). (4) A procedure for an order to cease unlawful detention of an adult in accommodation provided (or arranged for) by a care home service or an adult placement service (which would cover situations such as that asserted in DC, above). Items (2), (3) and (4) above would form a proposed new part 5A of the 2000 Act.

How they would work

The following is a truncated outline of the proposed new provisions. For a full description, see www.tcyoung.co.uk/legal-services/adult-incapacity-law/

For (1) above, a certificate by the medical practitioner primarily responsible for the treatment or assessment of the adult would provide authority to do what is reasonable to stop the patient going out of the hospital, including using medication for that purpose. No use of force would be permitted unless immediately necessary, and then only for so long as necessary in the circumstances. No action inconsistent with any court decision would be permitted.

The authority would last as long as there is an immediate need for such preventative measures. There would be right of appeal to the sheriff by the adult or by anyone claiming an interest in the adult’s personal welfare. Administration of medication to prevent leaving would be appealable under the existing s 52. The responsible medical practitioner would be required to review the adult’s capability from time to time, and revoke the authority if the adult is no longer incapable in relation to decisions to leave. The patient or any person having an interest could also apply to the sheriff to set an end date.

For (2) and (3), major responsibility would be placed on “relevant persons” – the manager of the premises, whom failing the adult’s social worker. The first step would be for the relevant person to refer the question of the adult’s capability to a medical practitioner “without delay”. If the medical practitioner certified incapacity, the relevant person would be required to initiate an assessment, subject to time limits. Under (2), any SRoL immediately necessary might be introduced during the assessment period. For (3), any necessary SRoL might thereupon be introduced.

Under (2), the next step would be a requirement for the relevant person to prepare a “statement of significant restriction” (SoSR), which specifies the measures to which the relevant person considers the adult’s liberty should be subject, and which explains why. Reports on the SoSR must be sought from the mental health officer (MHO) and a defined medical practitioner. The SoSR may be revised in the light of the reports. Any unresolved disagreement must be referred to the sheriff.

Once the SoSR has been finalised, implementation of the proposed restrictions may be authorised by welfare attorneys, welfare guardians, or (failing either, or authorisation by either) the sheriff. Interestingly, and potentially controversially, welfare attorneys and welfare guardians will be presumed to have power to authorise unless that is expressly excluded in the power of attorney document or guardianship order. Accordingly, against the eventuality that this provision is enacted in such terms, practitioners taking instructions to prepare powers of attorney now require to take instructions as to whether power to authorise a SRoL should be excluded. This should also be considered when drafting guardianship applications.

The draft legislation contains provisions regarding intimation of authorisation to the Mental Welfare Commission; and provisions regarding duration, renewal, variation and rights of appeal to the sheriff.

Under (4), the adult or any person claiming an interest in the adult’s personal welfare may apply to the sheriff for an order requiring the manager of the relevant accommodation, or any person detaining the adult there, to cease detaining the adult. If the sheriff is satisfied that the adult is detained unlawfully, the order must be granted; if not, it must be refused. This procedure is in addition to all other provisions of the 2000 Act and of the Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003, and does not limit or affect them in any way. Section 291 of the 2003 Act is the existing equivalent provision in that Act, and is amended to recognise the creation of this new remedy.

Demands on the system

Enactment of these proposals will place additional demands on MHOs, as will enactment of the provisions of the current Mental Health Bill. There are already insufficient MHOs to meet existing statutory requirements within time limits prescribed by statute (notably the 21-day time limit under s 57(4) of the 2000 Act for MHO reports for applications under part 6 of that Act). It would seem to be essential that the Scottish Government should now promote and resource the recruitment, training and retention of substantially more MHOs.

The specialist nature of this new regime will strengthen the arguments for shrieval specialisation in adult incapacity matters.

We must wait to see whether Scottish Government will at long last follow England in considering the changes (if any) which require to be made to the 2000 Act to secure compliance with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities of 13 December 2006; and whether the opportunity will be taken to make those and any other appropriate amendments to the 2000 Act.

The Commission’s report, written with commendable clarity, may be downloaded from the Commission’s website www.scotlawcom.gov.uk, or purchased from TSO: www.tsoshop.co.uk

Powers of attorney: Inner House to rule

The Court of Session is to be asked to resolve the uncertainty about whether substantial numbers of historic powers of attorney qualify as continuing and/or welfare powers of attorney in terms of the Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000, Adrian Ward writes. The issue concerns documents which are not explicit as regards the requirements of s 15(3)(b) or (ba), in the case of continuing powers, or s 16(3)(b) or (ba), in the case of welfare powers (see Journal, October 2014, 20). In NW, 2014 SLT (Sh Ct) 83, Sheriff Baird at Glasgow held that a purported continuing power of attorney was not valid as such. In B and G v F (7 August 2014), Sheriff Murray at Forfar disagreed in one respect with Sheriff Baird and held that the document in that case did qualify as a continuing power of attorney. Similar issues potentially affect welfare powers of attorney.

No advantage was taken in NW of the route of appeal under the 2000 Act, s 14 to the sheriff principal and thence, with leave, to the Court of Session. The Public Guardian has now announced that she will be party to a special case to be lodged shortly in the Inner House, to determine the validity as a continuing power of attorney of another document where similar issues have arisen.

In this issue

- Factors in the balance

- Balancing the right to decide

- Life yet in oil and gas

- Commercial awareness begins at trainee stage

- Relocation and the finances of contact

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion: Archie Maciver

- Book reviews

- Profile

- President's column

- Up and running at last

- People on the move

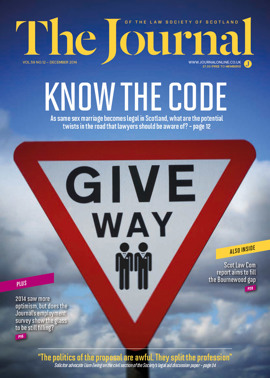

- With this Act, I thee wed

- Tax: a mission to inform

- For better, for worse

- Filling the Bournewood gap

- Power talking

- For whose aid?

- Balanced view

- A laughing matter?

- Directors: how much is too much, or not enough?

- Credit where it's due?

- New age, new image, new media, continuing problems?

- Scottish Solicitors Discipline Tribunal

- Lawyers as leaders

- Property Law Committee update

- Property Standardisation Group update

- Over the finishing line – 2

- Not proven no more?

- Vulnerable clients guidance now extended to the young

- From the Brussels office

- Take it to the schools

- A future – a vision

- Ask Ash

- A strategy with legs?

- Who's got what it takes?

- I can act, but should I?

- Prominence unplanned