For whose aid?

It takes an unusual turn of events for the Scottish Government to be claiming to uphold the broad availability of legal aid against cuts proposed by the Law Society of Scotland. But that is what happened in the wake of the discussion paper issued by the Society last month, Legal Assistance in Scotland: Fit for the 21st century. How did this come about, and is the charge accurate?

Solicitors are not heard praising the level of legal aid fees in Scotland. While the Government has refused to countenance the Westminster approach of withdrawing legal aid from large areas of civil work, successive restrictions have resulted in a 2014-15 budget of £132.1 million – the same as the amount spent in 1994-95, but in real terms worth only 57.6% of that. The former Cabinet Secretary for Justice Kenny MacAskill repeatedly insisted that there was no more money available, and it is unlikely that Michael Matheson, his successor, will take a different line. What the Society’s paper therefore seeks, in essence, is to make the most efficient use of the money provided.

Setting the scene for its proposals, it describes the structure that has evolved since 1986 as “a complex system that lacks clarity and is administratively burdensome”. The accounting process is too complex and time consuming, and solicitors cannot even be confident of receiving fair payment for work undertaken in good faith, giving rise to regular disputes and inconsistent outcomes. Neither criminal nor civil provision is structured to ensure the swift delivery of justice, nor has it kept pace with developments in legislation and the common law.

Criminal incentive

Starting with criminal provision, the approach put forward is that instead of separate categories of criminal advice and assistance, “criminal ABWOR”, and summary and solemn legal aid, there would be a single criminal legal assistance certificate, with financial verification at initial application stage only – eligibility criteria to be further discussed – and block fee systems for both summary and solemn work, except that trials would be separately chargeable by time. There would be no means test for anyone detained in a police environment.

The paper suggests that summary legal aid can be easier to obtain than ABWOR, providing an incentive to plead not guilty. Ian Moir, the Society’s criminal legal aid convener, argues that this hinders the efficient operation of the justice system, for which the thrust of recent reforms has been “to get information to the relevant people to try in appropriate cases to have the case resolved as early as it can be”.

Solicitor advocate Liam Ewing questions the paper’s approach. “The suggestion that the current system provides an incentive for not guilty pleas is followed by the proposal to front load the fee structure – which is in effect an incentive to plead guilty, by the same logic”, he told the Journal. “I can see why the Government should be attracted by this, but why should lawyers seek such an outcome?”

But, according to Moir: “We’re just reiterating that we want to see that there isn’t a disincentive to resolve cases early.” Accepting that striking the right balance is difficult, he adds: “No system is ever perfect. There have been substantial savings since they brought in ABWOR, but the difficulty is people tell you they have done a plea that falls within the scheme but then the Board takes a different view, so there needs to be a clarity and a confidence that when you do the work in good faith, you know you are going to be paid.”

Civil controversy

It is the civil legal aid proposals, however, that principally attracted criticism – as the authors rather expected. Civil legal aid convener Mark Thorley told the Journal: “There wasn’t consensus about what we were putting into print here, so we always knew it was unlikely we were going to reach consensus in the wider profession.”

A parallel streamlining to that envisaged for criminal, with a single continuing certificate (renewable at key stages if a matter progresses from advice to litigation), is put forward in place of the dual advice and assistance/civil legal aid schemes; and revised eligibility limits would remove from the scope of legal aid those whose assessed contribution is so high that they may not benefit at all. Further, and here is the rub, the paper suggests that certain areas of work could be considered for removal from the scope of civil legal assistance – contingent, crucially, on “there being a properly funded and widely available advice network, separate to the traditional network of firms of solicitors providing pro bono and legal assistance work”.

Types of work earmarked in this way are:

- breach of contract;

- debt;

- employment law;

- financial only divorce;

- housing/heritable property; and

- personal injury (except medical negligence).

Why? “We believe”, the paper states, “that the types of issues that would be removed from legal assistance by excluding the suggested areas are such that could easily and properly be provided either by the advice sector or on a private client basis through a range of funding options including speculative fee agreements, loans for legal services and payment plans involving deferral or instalments.”

It emphasises that if this course is taken, “it is critical that the organisations that currently provide high-quality specialist advice in many of these areas... are able to continue to provide such advice with the confidence of secure and adequate funding”.

Law centres: most to lose?

But law centres are one of the types of bodies the paper principally has in mind as continuing sources of advice. Law centres rely heavily on legal aid fees as a source of income. And it is the law centres that were quickest to raise their voices in protest.

“Thousands of people depend on legal aid to compensate them when they suffer injuries, when they are threatened with eviction for rent or mortgage arrears, when they are homeless, where they are unlawfully dismissed or discriminated against”, Paul Brown of Legal Services Agency wrote in the press. “The drafters of the report seem comfortable that their proposals would result in the collapse of access to core areas of civil justice for the most vulnerable in our society. They need the specialist skills of legal aid lawyers.”

In similar vein, Mike Dailly of Govan Law Centre, speaking for the Scottish Association of Law Centres, wrote: “In our view and experience, this is a socially regressive proposal that would penalise the most vulnerable and disadvantaged people in our society, taking Scotland backwards in time by more than half a century, to a pre-1950 era when there was no civil legal aid.”

Both called for the “divisive” and “ill-considered” paper to be withdrawn.

Before going further, it should be highlighted that on one crucial point the paper has left itself open to different interpretations. Moir and Thorley confirmed to the Journal that the civil and criminal teams worked separately on their proposals. Yet their paper is being read in several quarters as proposing to increase criminal fees at the expense of civil legal aid – including by the then Justice Secretary Kenny MacAskill, replying to a parliamentary question to similar effect from his backbench colleague Roderick Campbell, advocate. If the Society is to achieve feedback based on a proper understanding of its proposals, it is time to make its intended meaning clear.

Brown notes a lack of clarity about what would replace civil legal aid in the areas under threat. However, he is in no doubt that the effect on law centres would be highly adverse. “We provide advice, assistance and representation to hundreds, if not thousands, of individuals a year in housing matters. This includes defended eviction for rent arrears, defended mortgage repossessions and homelessness cases. These cases are generally complex and contentious. If we didn’t get legal aid, we would need exactly the same amount of money from other sources.”

Areas such as housing, employment and reparation, he adds, need to be seen as mainstream for solicitors’ involvement. “The flexibility and independence provided by civil legal aid makes this possible.” And while the paper duly recognises that professional assistance may be necessary in order to protect article 6 ECHR rights, Brown maintains that: “These areas of law will only develop and the article 6 rights of the citizens concerned be protected if solicitors continue to be involved.”

Reinvestment strategy

Thorley agrees that special funding measures would be needed for law centres to continue to deal with these cases, but insists that the purpose of the exercise is not to save the Government money.

“What we’re trying to do is to reinvest in the system. At the present it is difficult to see, certainly in terms of advice and assistance, how this is sustainable in the long term for solicitors. But at the same time there aren’t large sums of money there for reinvestment, so we have to look at it with a bit of blue sky thinking about how we can generate the reinvestment to ensure that the system survives in the future.”

So the money being ploughed back would not necessarily be reflected in solicitors’ fees?

“I think that would be the ultimate goal: to make sure that solicitors are paid at a proper rate for the work that they do. Because at the moment the rate for advice and assistance hasn’t changed in decades, and I cannot see how it can survive in the long term based on its current rates.”

Denying that the most needy would be hit, he adds: “What we are saying is that there should be other places you can go for the type of advice that you need, without it having to be solicitor led. There may be some cases that need to be solicitor led and we would want to make sure that that happened, but in general there may be places that people can go to get this legal advice without it having to be dealt with under advice and assistance.”

The paper does not attempt to project the level of savings – and reinvestment – that might be achieved. Asked if the Society has the necessary information to ensure that money saved is actually ploughed back, Thorley replies: “It’s a very difficult costing exercise, all of this. We are tentatively putting some figures together to see what it may be possible to save. It was very much an idea about how we can move forward, where we can move forward; there are no hard and fast figures... What we do know is we think it is unsustainable at the moment.”

Brown is unconvinced on this last point. “Unless a policy decision is taken that advice and assistance rates are not increased ever, then I can see no reason why advice and assistance should not be sustainable in the long term,” he asserts.

Ewing, who practises in both civil and criminal cases, similarly has a basic objection to the line taken. “The test for any legal aid reform should be whether it increases access to justice”, he states. “This proposal is little more than special pleading dressed up as reform.

“In an era of austerity welfare cuts and declining living standards, is the Society seriously suggesting that in housing and debt actions the poor should not have lawyers? I simply cannot accept that as a matter of principle and I am disappointed, to say the least, that the Society would countenance it.”

Political appeal

Both raise a wider point about whether the Society has gone the right way about winning public support.

“The approach currently taken by the Society would appear to me to be unlikely to garner support from many people at all”, Brown claims. “The case for change to criminal legal aid is not properly set out in the paper, and in mooting major cuts it reduces any support that people may be prepared to give.”

Ewing puts it this way: “The politics of the proposal are awful. They split the profession on the key issue of access to justice. As someone with experience of lobbying politicians, I can assure you that those who act for poor people fighting eviction will receive a much more sympathetic hearing than the criminal bar. Finally, I feel the most pernicious aspect is that it concedes the fundamental principle of the general availability of legal aid. As events south of the border illustrate, once that is surrendered there’s no knowing where we might end up.”

The paper is expressly labelled as for discussion, and it attempts to reassure readers of its commitment to ensuring that no deserving individual is left without proper advice. But it has left a hostage to fortune through its proposed reshaping of the civil system – one that may prevent proper attention being given to the document as a whole.

In this issue

- Factors in the balance

- Balancing the right to decide

- Life yet in oil and gas

- Commercial awareness begins at trainee stage

- Relocation and the finances of contact

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion: Archie Maciver

- Book reviews

- Profile

- President's column

- Up and running at last

- People on the move

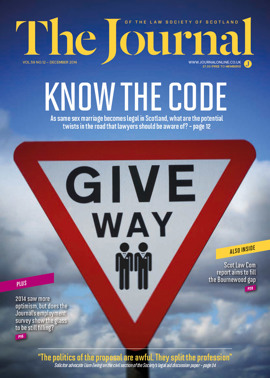

- With this Act, I thee wed

- Tax: a mission to inform

- For better, for worse

- Filling the Bournewood gap

- Power talking

- For whose aid?

- Balanced view

- A laughing matter?

- Directors: how much is too much, or not enough?

- Credit where it's due?

- New age, new image, new media, continuing problems?

- Scottish Solicitors Discipline Tribunal

- Lawyers as leaders

- Property Law Committee update

- Property Standardisation Group update

- Over the finishing line – 2

- Not proven no more?

- Vulnerable clients guidance now extended to the young

- From the Brussels office

- Take it to the schools

- A future – a vision

- Ask Ash

- A strategy with legs?

- Who's got what it takes?

- I can act, but should I?

- Prominence unplanned