Scottish Solicitors Discipline Tribunal

Scott Allan

A complaint was made by the Council of the Law Society of Scotland against Scott Allan, solicitor, Anderson Bain LLP, Aberdeen. The Tribunal found the respondent not guilty of professional misconduct but remitted the complaint to the Council under s 53ZA of the Solicitors (Scotland) Act 1980.

In this case the respondent had received an offer from an internal client for the purchase of heritable property at a particular price subject to conditions, and before acceptance the offer was verbally withdrawn due to difficulties relating to funding. The respondent intimated to the agents acting for another party who had previously registered a note of interest that the property was back on the market. This led to another offer being received on behalf of these clients, for a slightly lower price. The respondent telephoned the other agents to indicate that this offer was acceptable in principle and that a qualified acceptance would be issued. Before that occurred, the internal client intimated that his offer was to be regarded as reinstated. The respondent, after discussing matters with his client, reverted to the solicitor acting for the clients who had made the lesser offer and advised them of the situation. The respondent was then instructed by his client to indicate to the lesser offerers that if they were prepared to increase their offer to the same as that offered by the internal client it would be acceptable. At this point the respondent invited the opinion of the lesser offerers’ solicitor as to whether he should withdraw from acting; this solicitor indicated that he did not believe there was any reason for the respondent to resign. The lesser offerers increased their offer to the same level as the internal offerer but stipulated that this was to include various expensive items of furniture. The respondent was instructed to break off contact with these lesser offerers and to conclude missives with the original internal offerer. At this stage the respondent withdrew from acting until after the conclusion of missives.

The Tribunal considered that a fully appraised bystander, having looked at the situation, would form the view that the respondent placed his integrity in question when he engaged in negotiations to increase the price to be paid for the subjects, having earlier indicated that a particular price was acceptable. However the respondent was not dishonest; he recognised that he was in a vulnerable situation and tried to seek clarity. He made the wrong decision which brought his integrity into question. The Tribunal however could not classify this as reprehensible, given that the way in which he acted was open and honest. The Tribunal considered that the respondent had made a significant error of judgment which was worthy of criticism. In the particular circumstances, given that the other solicitor acting indicated he had no difficulty in the respondent continuing to act, the Tribunal found the respondent not guilty of professional misconduct. The Tribunal however considered that the respondent’s conduct might amount to unsatisfactory professional conduct and accordingly remitted the complaint to the Society.

Graeme Stark Herald

A complaint was made by the Council of the Law Society of Scotland against Graeme Stark Herald, solicitor, formerly of Herald & Co, Arbroath. The Tribunal found the respondent guilty of professional misconduct in respect of his breach of rule 4 of the Solicitors (Scotland) Accounts etc Rules 2001 and his stealing and embezzling funds belonging to his clients over a lengthy period of time in order to fund his personal lifestyle and professional practice.

It was quite clear to the Tribunal from the evidence that the respondent had been engaged in a scheme over an extended period of time where having utilised client funds for his own benefit, other client funds were used to repay sums embezzled, with an increasing balance being due on his client account which he was ultimately unable to cover through realisation of property owned by himself and his wife. There was a shortfall of almost £500,000. The Tribunal considers that this type of behaviour is totally contrary to the standards expected of a competent and reputable solicitor and seriously undermines the public’s confidence in the profession. The Tribunal had absolutely no hesitation in striking the respondent’s name from the Roll of Solicitors in Scotland. Publicity was deferred until after the conclusion of criminal proceedings.

Colin Neil Macleod

A complaint was made by the Council of the Law Society of Scotland against Colin Neil Macleod, solicitor, Cumbernauld. The Tribunal found the respondent guilty of professional misconduct in cumulo in respect of his convictions for nine offences committed between June 2009 and January 2012 (breach of the peace, culpable and reckless conduct (both with a knife), obstruction of ambulance staff, two assaults, threatening behaviour, drink driving, threats to police and attempting to pervert the course of justice by a false identity), the commission of three of the said offences whilst on bail, and his failure to attend a deferred sentence hearing in relation to two of the offences as a result of which a warrant was granted for his arrest.

The Tribunal censured the respondent and directed in terms of s 53(5) of the Solicitors (Scotland) Act 1980 that any practising certificate held or to be issued to the respondent shall be subject to such restriction as will limit him to acting as a qualified assistant to (and to being supervised by) such employer or successive employers as may be approved by the Council or its Practising Certificate Subcommittee, and that for an aggregate period of at least five years and thereafter until such time as he satisfies the Tribunal that he is fit to hold a full practising certificate.

The Tribunal considers that high standards of propriety are expected of members of the legal profession and that solicitors have a duty to act with integrity, and this duty extends to both personal and professional conduct. There is a close working relationship among solicitors and between solicitors and the courts, frequently involving an element of trust and respect. The Tribunal considered that a solicitor has a duty not to act in a manner which has a negative impact on that working relationship or which damages that mutual trust and respect. In addition, a solicitor has a duty not to act in a way which brings the profession into disrepute. The Tribunal accordingly made a finding of professional misconduct. The Tribunal considered that in order to protect both the public and the respondent, there should be a restriction on the respondent’s practising certificate for an aggregate period of five years.

Gerard Noble Nesbitt

A complaint was made by the Council of the Law Society of Scotland against Gerard Noble Nesbitt, c/o HM Prison Castle Huntly. The Tribunal found that the respondent had been convicted of an offence in the High Court and sentenced to a period of imprisonment of three years, six months and that accordingly s 53(1)(b) of the Solicitors (Scotland) Act 1980 applied to the case. The Tribunal struck the respondent’s name from the Roll of Solicitors in Scotland.

It was clear that this was a serious conviction of being concerned in the supply of a controlled drug. The only mitigation put forward by the respondent was his letter wherein he had set out his defence to the original charge. The Tribunal could not look behind the conviction. The respondent had shown remorse in both of his letters and had co-operated fully with the Society. However, members of the public must have a well founded confidence that any solicitor whom they instruct will be a person of unquestionable integrity, probity and trustworthiness. As a solicitor, the respondent was a member of a profession where a high standard of ethical conduct was required. The Tribunal concluded that there was no measure, short of striking the respondent’s name from the roll, which was compatible with the serious nature of this conviction, and the obvious damage caused to the reputation of the profession. The existence of a previous conviction for an analogous offence reinforced this conclusion.

Anthony Quinn

A complaint was made by the Council of the Law Society of Scotland against Anthony Quinn, solicitor, Kilsyth. The Tribunal found the respondent guilty of professional misconduct in respect of (1) his failure (a) to produce practice information for inspection by the Society, contrary to rule 6.18.3 of the Law Society of Scotland Practice Rules 2011; and (b) to provide reasonable co-operation to the persons authorised by the Society in the conduct of the said inspection, contrary to rule 6.18.17 of said Rules; (2) his failure (a) to respond timeously, accurately or fully or to communicate effectively in response to correspondence or statutory notices sent to him by the Council; and (b) to respond promptly and efficiently to correspondence or statutory notices received from the Council in respect of its regulatory function.

The Tribunal censured the respondent and directed in terms of s 53(5) of the Solicitors (Scotland) Act 1980 that any practising certificate held or issued to the respondent shall be subject to such restriction as will limit him to acting as a qualified assistant to such employer as may be approved by the Council of the Society or its Practising Certificate Subcommittee, for an aggregate period of five years and thereafter until such time as he satisfies the Tribunal that he is fit to hold a full practising certificate.

The respondent did not lodge answers or attend the Tribunal and evidence was led. The Accounts Rules are a very important and fundamental provision for the protection of the public. The respondent had clearly failed to comply with the accounts inspection process. Throughout, he had been given repeated opportunities to produce the information required. He had failed to do so. This was clearly conduct that fell well below the conduct to be expected of a competent and reputable solicitor and would undoubtedly be regarded by any reputable solicitor as serious and reprehensible. Additionally, the respondent had failed to respond to the Society on repeated occasions. These failures were a breach of the duty owed under the Practice Rules regarding effective communication and a breach of the respondent’s duty to respond to his regulatory body. The Society clearly has a statutory duty to protect the interests of the public. The respondent’s complete failure to co-operate with his professional body could be seriously detrimental to the public trust in solicitors.

In this issue

- Factors in the balance

- Balancing the right to decide

- Life yet in oil and gas

- Commercial awareness begins at trainee stage

- Relocation and the finances of contact

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion: Archie Maciver

- Book reviews

- Profile

- President's column

- Up and running at last

- People on the move

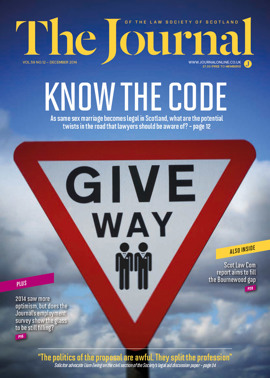

- With this Act, I thee wed

- Tax: a mission to inform

- For better, for worse

- Filling the Bournewood gap

- Power talking

- For whose aid?

- Balanced view

- A laughing matter?

- Directors: how much is too much, or not enough?

- Credit where it's due?

- New age, new image, new media, continuing problems?

- Scottish Solicitors Discipline Tribunal

- Lawyers as leaders

- Property Law Committee update

- Property Standardisation Group update

- Over the finishing line – 2

- Not proven no more?

- Vulnerable clients guidance now extended to the young

- From the Brussels office

- Take it to the schools

- A future – a vision

- Ask Ash

- A strategy with legs?

- Who's got what it takes?

- I can act, but should I?

- Prominence unplanned