With this Act, I thee wed

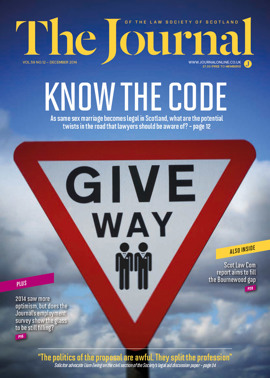

On 16 December 2014, the Marriage and Civil Partnership (Scotland) Act 2014 comes into force. Its primary purpose is to make provision for the marriage of people of the same sex. If couples make the necessary arrangements, and many already have, the first marriage ceremonies between people of the same sex in Scotland will take place on 31 December 2014.

This article highlights provisions which should give practitioners cause to reflect when providing advice to same sex couples before, during, or after civil partnership or marriage.

The Act does not create a "new institution" of marriage for people of the same sex; rather, it repeals legislation that previously excluded same-sex couples from participating in an institution only open to those of the opposite sex.

Section 5(4)(e) of the Marriage (Scotland) Act 1977, which made being of the same sex as oneís potential spouse an impediment to marriage, is now repealed.

The definition of marriage is reformulated thus: "marriage means marriage between persons of different sexes and marriage between persons of the same sex (and any reference to a person being (or having been) married to another person, or to two people being (or having been) married to each other, is to be read accordingly)" (s 4(15)).

From 1 January 2015, there will be three types of recognised, regulated relationships in Scotland in which same sex couples can participate: civil partnership, marriage, and cohabitation. Opposite sex couples remain able only to cohabit or marry.

On one view, the majority of the Actís provisions might be regarded as simply aligning marriage law in order that there is an equality of provision for opposite sex and same sex marriage. The Act is, however, a wide ranging piece of legislation which requires early, careful consideration.

Significantly, under part 4, a civil partner or spouse can now obtain full recognition of a change of gender without the necessity of dissolution or divorce. This former rule caused real distress where one party transitioned gender and the couple required to go through dissolution or divorce, even if that was not what they wished.

The Act makes practical provisions in respect of the solemnisation of marriage (ss 12-15), including the authorisation of belief celebrants and religious celebrants to solemnise same sex marriage should they agree to do so.

In its more unusual provisions, the Act also makes changes to longstanding common law. Section 7 abolishes the defence to a charge of reset previously available to wives who received or concealed goods stolen by their husband. Under s 28, bigamy becomes a statutory rather than a common law offence.

At this early stage in the life of the Act, however, family law practitioners are likely to be consulted by parties to a civil partnership who wish to change to marriage or parties not in civil partnership who wish to marry.

Effect of the choice

Following implementation of the Act, same sex couples have the choice either to enter into civil partnership or to marry.

If a client seeks advice about entering into a civil partnership, it is essential to explain the option subsequently to change to marriage and the issue of backdating, discussed later.

If a client is marrying, the same advice that would be given to a person marrying someone of the opposite sex applies in respect of the provisions of the Family Law (Scotland) Acts 1985 and 2006.

From civil partnership to marriage

Civil partnerships were introduced by the Civil Partnership Act 2004, which made provision for same sex couples to enter into a civil partnership, based closely upon marriage. Research carried out by the Equality Network calculates that around 500 couples per year enter into a civil partnership – roughly 2% of the marriage rate between opposite sex couples.

Whereas opposite sex couples could marry by participating in a religious, humanist or civil ceremony, same sex couples could only enter into a civil partnership. Although a civil partnership offers almost identical rights and responsibilities to marriage, many same sex couples perceived that they did not receive the same recognition as married couples.

Sections 8-11 of the Act make provision for partners in a "qualifying civil partnership" to change their partnership to marriage. To be a qualifying civil partnership, it must have been registered in Scotland and must not have been annulled, dissolved or ended by the death of one of the partners.

Civil partnership can change to marriage by way of an administrative route, where the parties meet with a registrar. They need not participate in a marriage ceremony. Alternatively, partners can choose to change by participating in a marriage ceremony, either civil, religious or belief.

The civil partnership "ends" when the marriage is solemnised and the partners are treated as having been married from the date of the registration of their civil partnership (s 11(2)). The period of the marriage is effectively backdated to commence from the date when the civil partnership was registered. This backdating applies to all qualifying civil partnerships that change to marriage and is not optional.

Beware the backdating

The inclusion of the period of civil partnership within the marriage may be intended to emphasise that a change from partnership to marriage is a symbolic one. Its retrospective nature is, however, unprecedented in previous family law legislation.

If practitioners are consulted before an existing civil partnership changes to marriage, they should explore fully the background to the change, so that clients can make an informed decision in the knowledge of potential consequences if there is a subsequent divorce.

Consider, for example, civil partners who separate for a period of time but do not dissolve the partnership. They decide to reconcile and change their partnership to marriage. Since the period of marriage is backdated to the registration of the partnership, no account is taken of the period of separation.

Assets acquired or divested of, or liabilities incurred during such a period of separation, would be included in the calculation of the net value of matrimonial property for the purposes of divorce.

This may give rise to arguments regarding economic advantage and disadvantage in terms of s 9 of the Family Law (Scotland) Act 1985. The valuation and apportionment of pension interests could arise. Special circumstances involving conduct and transactions during the partnership or a period of separation before marriage could be relevant.

Practitioners currently instructed in the drafting of a minute of agreement relative to dissolution of a civil partnership should consider this scenario much in the same way that they would the potential resumption of cohabitation between separated spouses.

Section 11(7) provides that any decree of aliment in force requiring one civil partner to aliment the other does not end because the partnership changes to a marriage. Section 11(8) provides that any order under s 103(3) or (4) of the 2004 Act which regulates occupancy rights to a family home in a partnership will likewise continue to have effect notwithstanding a change to marriage.

Separating same sex couples

Given that the 2014 Act is in its infancy, it is unlikely that family lawyers will encounter the traditional "January rush" in relation to divorcing same sex couples.

In respect of legal proceedings, s 5(1) confirms that the voidability of a marriage where one of the parties at the time of the marriage is permanently and incurably impotent in relation to the other spouse only applies to opposite sex marriage.

Section 5(2) provides that "adultery" has the same meaning for the purposes of the Divorce (Scotland) Act 1976 for same sex couples as for opposite sex couples. Effectively, only sexual intercourse with a person of the opposite sex will constitute adultery. A spouse in a same sex marriage where there has been unfaithfulness would, however, have grounds to establish that the marriage had broken down irretrievably as a result of the conduct of their spouse in terms of s 1(2)(b) of the Divorce (Scotland) Act 1976.

The principles of the Family Law (Scotland) Act 1985 will be used in determining the issue of financial provision on divorce.

Foreign dimension and the last resort

The Act provides, through further amendments to s 5(4) of the 1977 Act, that although a same sex marriage would be void according to the law of the domicile of one or both of the parties, that does not prevent them being married in Scotland. This will allow same sex couples who cannot access equal marriage in their domicile to be married here.

Couples who marry in Scotland in these circumstances should consider the implications of their choice, particularly if they then return to live in a domicile that does not recognise equal marriage. If they later separate in that domicile, they could find themselves unable to be divorced there.

The implications are apparent. The Act (in sched 1) does, however, make provision for a "jurisdiction of last resort". Edinburgh Sheriff Court has jurisdiction to entertain proceedings for divorce or separation of the parties to a same sex marriage if the parties married each other in Scotland, if there is no other court recognised as having jurisdiction and if it is in the interests of justice to assume jurisdiction.

If spouses had to utilise the "jurisdiction of last resort" in these circumstances, it is probable that they would require to return to Scotland and to instruct solicitors here. Financial provision would be determined in terms of the Family Law (Scotland) Act 1985 as amended, or any re-enactment thereof extant at the time, rather than the rules which might apply for opposite sex marriage in their domicile.

In addition, the Act provides for extension by order of the categories of civil partnership which can transfer to marriage in Scotland. This may be utilised to allow a civil partnership registered in another country to be changed to marriage in Scotland. Parties who entered into a civil partnership in another country before civil partnership was recognised in Scotland could find their marriage backdated even further.

The future for couples?

From 16 December 2014, the choices available to couples who wish to regulate and recognise their relationship will increase. However, their availability still depends on the sexual orientation of the parties to the relationship.

The availability of civil partnership to opposite sex couples is something that many consider the next step in the equal recognition of status of same and opposite sex relationships.

Tim Hopkins of the Equality Network, which campaigned for equal marriage in Scotland, says: "The opening up of civil partnership to mixed sex couples is the unfinished business of this legislation. The Scottish Government has promised to consult on this early in 2015, but it is likely to be 2016 at the earliest before legislation could start to be considered. We hope that the eventual outcome will be the same three choices available to all: cohabitation, civil partnership or marriage."

It will be interesting to see whether same sex couples begin to treat civil partnership as a "halfway house" that is more formal than cohabitation but less onerous than marriage. There may be a temptation to enter into civil partnership as a "trial run" before what is perceived as the more established institution of marriage. While that might not have been the case previously when civil partnership was the only option available to same sex couples, it is important that practitioners remain conscious that civil partnership and marriage confer equivalent rights and responsibilities and that civil partnership remains an institution in its own right.

It is likely that the full implications of the provisions of the Act discussed here will not become apparent until they are tested – which, unfortunately, is most likely to happen on the breakdown of a same sex marriage. Having an early awareness of these issues should help practitioners to give advice that has an eye to the future and which addresses the potential pitfalls for clients exiting the "new institution" of same sex marriage.

In this issue

- Factors in the balance

- Balancing the right to decide

- Life yet in oil and gas

- Commercial awareness begins at trainee stage

- Relocation and the finances of contact

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion: Archie Maciver

- Book reviews

- Profile

- President's column

- Up and running at last

- People on the move

- With this Act, I thee wed

- Tax: a mission to inform

- For better, for worse

- Filling the Bournewood gap

- Power talking

- For whose aid?

- Balanced view

- A laughing matter?

- Directors: how much is too much, or not enough?

- Credit where it's due?

- New age, new image, new media, continuing problems?

- Scottish Solicitors Discipline Tribunal

- Lawyers as leaders

- Property Law Committee update

- Property Standardisation Group update

- Over the finishing line – 2

- Not proven no more?

- Vulnerable clients guidance now extended to the young

- From the Brussels office

- Take it to the schools

- A future – a vision

- Ask Ash

- A strategy with legs?

- Who's got what it takes?

- I can act, but should I?

- Prominence unplanned