Simple procedure – it's complicated

On 28 November 2016, the new simple procedure was introduced to the Scottish courts system. It potentially heralds a major change in the way that what were previously small claims and summary cause cases are dealt with. There is a new fee structure, more of a case management approach, the language has been simplified (although there is more work to do on this), and an encouragement to use alternative dispute resolution mechanisms, where appropriate, to provide a more party-focused and proportionate approach.

As director of Scottish Mediation, you would think I’d be welcoming this change wholeheartedly, and I do. But as I say above, it’s complicated.

On one hand, I welcome the approach, as from my experience as a pro bono mediator at the Edinburgh Sheriff Court Mediation Project, I have seen numerous cases settled where the parties are given an opportunity to discuss how they feel about their case with the other party, and then come to a settlement that they have both constructed. Having watched similar cases in court, I think it is important that people have a choice on how they can resolve their disputes, and this choice should be available across Scotland.

On the other hand, while there are now good resources available online through the mygov.scot website, which you can link from the Scottish Courts website, accessing mediation is not yet an integral part of the system. Until it is, I think it is unlikely that there will be a great level of takeup.

How should simple procedure work?

The new Simple Procedure Rules will apply to all civil cases where the money being claimed is less than £5,000, and replace the old Small Claim and Summary Cause Rules.

The applicant fills out one of the new simple procedure claim forms, which will be printed out and can either be posted or taken into the court. For actions under £200, the cost is £18 and for those between £200 and £5,000, the cost is £100, which must be paid when the form is submitted. There are fee exemptions based on income.

Once the form is received, if the claim is contested, within two weeks the sheriff will produce first written orders. These can direct one of five courses of action: (1) refer parties to alternative dispute resolution; (2) arrange a case management discussion; (3) arrange a hearing; (4) if the sheriff thinks that a decision could be made without a hearing, indicate that the sheriff is considering doing so; (5) use the sheriff’s powers to dismiss a claim or decide a case.

Within simple procedure, during the case management discussion, the sheriff may (a) discuss the claim and response with the parties and clarify any concerns the sheriff has; (b) discuss negotiation and alternative dispute resolution with the parties; (c) give the parties, in person, guidance and orders about the witnesses, documents and other evidence which they need to bring to a hearing; (d) give the parties, in person, orders which arrange a hearing.

Should the case not be resolved, the final part of the procedure would be for a hearing, which it is anticipated will be similar to current proofs.

Within simple procedure, the key differences are around the advice available online before the intended action is submitted, and then once that is done, through the first written orders and the case management discussion. It is clear that there is an intention for the parties to be able to use different forms of dispute resolution. Indeed sheriffs are encouraged to ask the parties to consider this and may refer parties to alternative dispute resolution at various stages during the procedure. This is part of an encouragement for the sheriff actively to manage cases.

What role could mediation play?

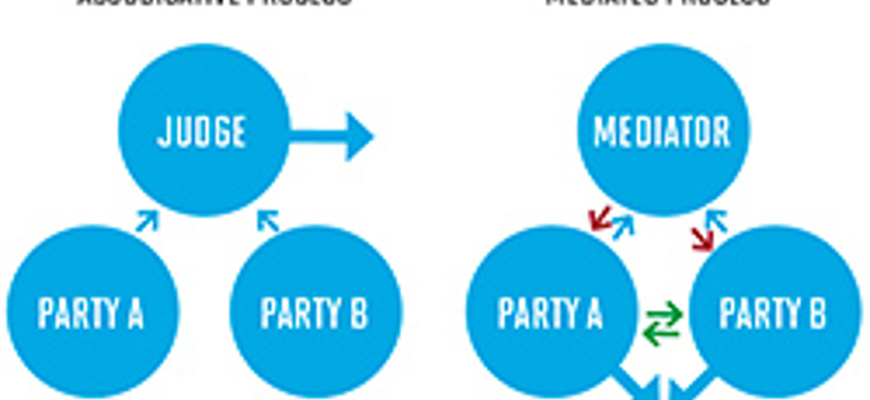

The following three sections are taken from The Guide to the Effective Use of Mediation in Court Actions, produced by the Judicial Institute Scotland and written by Charlie Irvine, senior teaching fellow at the University of Strathclyde Law School. It sets out the process of mediation as follows:

Key elements

“Mediation is a conversation between two or more people that disagree, led by a trained, neutral mediator” (New York Peace Institute, provider of in-court mediation in New York City).

This definition highlights some key features:

- Conversation – mediation requires the parties to speak directly to each other rather than make their case to a judge. Disagreement – mediation can be effective in highly entrenched disputes.

- Leadership – the mediator is not simply a passive bystander but takes a proactive role in seeking a solution.

- Training – mediators must fulfil a training and practice requirement (in Scotland, standards are set by the Scottish Mediation Register).

- Neutral – mediators must act as impartial third parties.

Mediation in simple procedure?

For sheriffs considering referral to mediation, it is useful to think of it as a form of facilitated negotiation. It is thus the parties who ultimately determine the content of any agreement, at times assisted by legal representatives. The mediator’s role is to lead the negotiation, ensuring procedural fairness (i.e. that both parties have the opportunity to state their case) and that any agreements accurately reflect the parties’ wishes.

Mediators typically do not take responsibility for the substantive fairness of mediation outcomes; however, when dealing with unrepresented parties, experienced mediators will often provide useful process information (timescales, terminology, etc). They may also engage in reality testing, ensuring that parties have carefully thought through the practical and legal consequences of their proposals.

What actually happens?

Most mediation sessions follow a simple five-stage process:

- Introductions

- Identify the issues

- Explore the issues: Parties exchange information and hear one another’s perspective

- Develop options

- Record agreement

Mediation sessions in smaller civil actions typically last between one and three hours, with all parties together most of the time; larger commercial matters tend to take a full day, with parties and representatives in separate rooms. The outcome is recorded in the form of a settlement agreement, signed by the parties. Mediation is conducted on a “without prejudice” basis, set out in a standard agreement to mediate.

How would parties access it?

Perhaps the biggest challenge around simple procedure, and the main reason for me that “it’s complicated,” is that the provision of mediation via the courts is not as it should be.

There are currently two projects where mediation is provided through pro bono services: at Edinburgh Sheriff Court via Citizens Advice and at Glasgow Sheriff Court via the University of Strathclyde Mediation project. They both are successful projects, enjoying great feedback from those using mediation and settlement rates of 70% and above. In both projects, sheriffs will often ask parties if they would like to consider mediation, and either an appointment will be made for a mediation or it will be done there and then.

In Dundee, Perth and Angus, parties are able to access an in-court advice service which provides a negotiation support for one of the parties, and in North Lanarkshire there is a scheme that offers mediation before cases get to court.

Aside from these projects, mediators and information about mediation can be accessed by contacting Scottish Mediation via its helpline or its website. A panel of mediators from the Edinburgh and Glasgow projects is being drawn together to provide mediation for simple procedure cases on a low-cost basis, which will be up and running in early 2017. Mediators on the panel will need to have experience in simple procedure cases, having completed a minimum number of cases and having passed a practice assessment. They will also need to be a member of the Scottish Mediation Register. As part of the register, a second-tier complaints process is in place should concerns about practice arise.

What does the future look like?

Discussions are underway to map out how parties might better access mediation and how it could become a more integrated part of the system. From the perspective of Scottish Mediation, there are several opportunities to do this. These could include: making mediation available as part of the court fee; having resolution centres based in every court, offering support on all aspects of dispute resolution and advice before and during the time cases go to court; and establishing easy access to telephone and online mediation so that parties do not have to travel to court to resolve their disputes.

In looking at the opportunities that exist, we should not be afraid to learn from others, and there are great examples of mediation integrated into civil justice systems across the globe that we can learn from in Scotland. Alberta in Canada and Ohio in the United States are just two that come to mind that work very successfully.

Such work will help us in Scotland to develop a truly simple procedure, and perhaps something that enhances our reputation for innovation by having a legal system fully focused on the parties.

In this issue

- Private prosecution: the Glasgow Rape Case revisited

- The commercialisation of space

- Feminism: all is not what it seems…

- Retaking the narrative on complaints

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion: Alan McIntosh

- Book reviews

- Profile

- President's column

- RoS riding to the four (hundred)

- People on the move

- Scot in the European hot seat

- When partners fall short

- Uber: a great gig?

- Brexit: the end of cross-border practice?

- Closing in: the gender pay gap rules

- Simple procedure – it's complicated

- When changing the defender is OK

- Solemn procedure: beware the changes

- Divorce and the new state pension

- Delivery of alcohol: a “game changer”?

- A tale of two "Budgets"

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- "One-shot" rule sees rejection income soar

- Law without frontiers

- CJEU decision supports LPP protections

- Society thank-you for STARTS support

- From the Brussels Office

- Law reform roundup

- Expertise plus: promoting a sector strength

- Paralegal pointers

- What to do about client interest?

- Still free to market?

- New year, new contact

- Ask Ash

- Paying homage to King Cash