Changing sides

The question of whether a solicitor owes a continuing duty of loyalty to a former client has been the subject of conflicting high-level judicial decisions in multiple jurisdictions. These include the House of Lords in Bolkiah v KPMG [1999] 2 AC 222, the Supreme Court of Canada in MacDonald Estate v Martin (1990) 77 DLR (4th) 249, the Supreme Court of New South Wales in Kallinicos v Hunt [2005] NSWSC 1181, and the Court of Appeal of Victoria in Spincode Pty Ltd v Look Software Pty Ltd [2001] VSCA 248. The Inner House recently considered the issue in Ecclesiastical Insurance Office v Lady Whitehouse-Grant-Christ [2017] CSIH 33 (26 May 2017).

The facts, so far as relevant to the issue of loyalty, can be summarised briefly. The defender attempted to claim on her home insurance policy with the pursuers (“EBS”) following a fire. EBS raised an action in 2000, seeking to avoid the policy for non-disclosure. The defender sought initial advice from George Moore, then a partner at HBM Sayers.

Moore’s involvement lasted around six weeks and only concerned the initial stages of the litigation. He expressly agreed to provide preliminary advice; enter appearance; sist the action; and submit a legal aid application. He met the defender and took a statement. He provided preliminary advice as agreed. However, it appears the defender entered appearance herself. Moore wrote explaining the main points of EBS’s case and his views on prospects. He then ceased to act and the defender instructed other solicitors.

After a nine-year sist, the defender, by then a party litigant, raised a counterclaim. In February 2015 the Lord Ordinary, following a debate, found in favour of EBS in the principal action and dismissed the counterclaim. The defender’s reclaiming motion was allowed on 2 March 2016.

Prior to a by order hearing, EBS changed solicitors to BLM, with whom they had a longstanding relationship. At the hearing, the defender sought that BLM and senior counsel representing EBS withdraw from acting, or alternatively an interdict preventing them from acting. This was on the basis that HBM Sayers had merged with BLM in May 2014 and Moore had become a consultant at the firm.

The majority found that there was no bar to BLM acting in these circumstances. Lord McGhie delivered the leading opinion with Lord Bracadale providing a short supporting opinion. Lord Malcolm dissented.

Protecting confidential information

The defender argued that BLM owed her a continuing duty of loyalty by virtue of Moore’s former involvement. Further, the court had an overriding jurisdiction to intervene to protect the due administration of justice.

All the judges agreed that the court has a power to intervene where necessary. They differed on whether that power should be exercised. Lord McGhie referenced the broad principle that justice should be seen to be done, but commented: “When the facts are fully understood there may be few cases where the properly informed public would have real cause of concern if no question of possible misuse of confidential information arose” (para 58).

For the majority, the real issue was one of access to confidential information. Indeed, it seems the defender’s submissions primarily proceeded on the basis of a risk of disclosure of privileged and confidential information she had provided to Moore.

Referring to the House of Lords in Bolkiah, the majority found there was no risk of confidential information being used by BLM to the defender’s detriment. The court considered it should examine documents lodged in a sealed envelope, a precognition taken by Moore from the defender’s husband, relied on by the defender. There was a suggestion that, if doubt arose, it would be for BLM to convince the court that there was no such risk. However, the majority concluded that there was no confidential information that could be passed from Moore to BLM that could prejudice the defender. Lord McGhie summarised the position (para 67): “Where confidential material could have no realistic bearing on any issues in dispute, there would be no reason to restrict disclosure within the firm and there would be no reason for disclosure outside the firm either to the opposing party – or, indeed, to any other party. There would be no justification for the court intervening to prevent disclosure when there was no reason to fear it happening.”

On the particular facts, it is perhaps easy to see why the majority found that BLM should not be prevented from acting. One reason was that the dispute had substantially narrowed from when Moore had been involved. The precognition did not relate to a live issue. It was also important that Moore’s role was limited to the very early stages of the litigation. In addition, he was now a consultant at the firm rather than a partner, and had no current involvement in the case.

In his dissenting opinion, Lord Malcolm took a different approach. He indicated that “once the solicitors are in receipt of confidential information, or cannot guarantee that they will not receive it, they should not act for a party with an adverse interest to the firm’s former client” (para 25).

That approach seems too strict. Where the information obtained by Moore was plainly no longer confidential, or indeed relevant to the dispute, it is difficult to see how the former client could have been prejudiced.

A duty of loyalty?

The court concluded that apart from the Australian state of Victoria and the USA, all common law jurisdictions regarded the issue as one of risk of disclosure of confidential information, rather than a “duty of loyalty”.

Whilst not expressly ruling out that a duty could exist, the majority are clear that there needs to be some special feature of the agency relationship first. The onus appears to be on the former client (Connolly and Connolly v Brown 2007 SLT 778). They were also clear that any duty of loyalty would lie with the solicitor, not the firm. The features of this case, in particular the passage of time, Moore’s limited role, his non-involvement while at BLM, and the narrowing of the issues in dispute, indicated that no such special feature existed.

However, Lord McGhie comments that he “[does] not find it difficult to envisage situations where the public would expect the court to intervene” (para 59). A direct change of sides by a solicitor in a litigation would clearly be one. Difficulties arise where the solicitor’s firm is engaged, with no involvement from the particular solicitor who acted for the former client.

The solution from the majority is pragmatic. Lord McGhie goes as far as to suggest (para 59) that: “It is to be expected that, in modern times of mergers and very large practices, solicitors may find themselves involved, in one role or another, in a firm acting against a client of a firm in which they were previously involved. Such cases raise a variety of practical factual problems as well as questions of the balancing of interests.”

Lord Malcolm’s dissenting view that there should be a general rule against a firm of solicitors, having acted on one side of a litigation, changing sides (he found support in the Australian case of Spincode) seems to be based on public perception: “I would expect the fair-minded member of the public to have sympathy with the former client faced with what could reasonably be described as an act of disloyalty, and to be concerned at the tarnish on the integrity and reputation of the judicial process” (para 23).

There are competing interests to balance: the interests of maintaining public confidence in the profession, against a solicitor’s freedom to act for other clients and the reality of a profession where large mergers are relatively common. The court having categorised the issue as one primarily of preventing access to confidential information, where there is even a suggestion of detriment to the former client the court has to step in to protect that client’s interest.

Regulatory intervention?

Lord Bracadale observes that great care must be taken by solicitors in this area. BLM had been aware of the problem before accepting the instruction. They had spoken in general terms with the Law Society of Scotland’s Professional Practice team and had taken advice from senior counsel. BLM also benefited from Moore’s clearly defined scope of work at his previous firm.

Whilst it is clear that an individual solicitor should not be entitled to switch from representing one party to a litigation to representing another, it seems that with adequate safeguards, that solicitor’s firm should not be prevented from taking the instruction. The court makes a number of references to information barriers or “Chinese walls”. The court was critical that no such barrier was in place in this case. As soon as the risk is identified, the files should be locked down. This is important where electronic files are easily searchable by anyone in a firm.

All the judges suggest that the Society may wish to intervene to provide guidance. Lord McGhie summarises the point (para 56), after accepting the lack of support in various jurisdictions for a duty of loyalty persisting after termination: “This does not exclude the possibility of a Law Society or professional body of lawyers treating the concept of loyalty as something to be encouraged and doing so in terms which may blur the line between loyalty to a client and persisting loyalty after the lawyer has performed the work for which he was instructed. Potential clients might like to hear that they are to receive some sort of long-term commitment. This might encourage them to regard the relationship as an enduring one. But such commitment will not easily be converted into a positive obligation. In the circumstances of the present case, it is not easy to see that it would, of itself, advance matters and, indeed, it is not really contended by the defender that it would… BLM as a firm have no duty of loyalty to the defender. Any duty would lie on Mr Moore.”

Lord Malcolm went as far as to suggest that the American Bar Association rules may provide some inspiration. Rules 1.7 and 1.9 establish a clear prohibition on an individual solicitor changing sides and acting against a previous client. These rules also extend (rule 1.10) to firms where one of the partners would be barred from acting, unless: (i) the lawyer is “timely screened from any participation in the matter and is apportioned no part of the fee therefrom”; (ii) the former client is informed of the situation; and (iii) the former client is provided with “certifications of compliance” at reasonable intervals.

The ABA rules may provide a useful starting point, and the focus on “screening” or information barriers is to be encouraged. However, it is also important not to lose sight of factors such as: (1) the involvement of the solicitor with the former client; (2) the role of the solicitor within the new firm; and (3) the passage of time. All of these inform whether it is appropriate for the solicitor to accept the instruction.

In this issue

- Neutrality policies in commercial companies

- Court IT: the young lawyers' view

- Human rights: answering to the UN

- Galo and fair trial: which way for Scotland?

- Secondary victims in clinical negligence

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion: Alan W Robertson

- Book reviews

- Profile

- President's column

- Twin tracks to completion

- People on the move

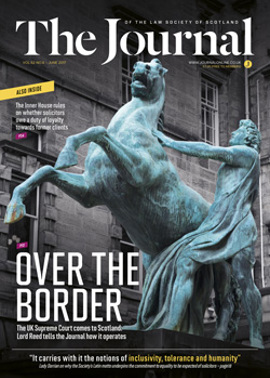

- Court of the nations

- Second time around

- How to avoid a summer tax scorcher

- Humani nihil alienum: a call to equality

- Sheriff commercial procedure: count 10

- Taking a pay cut: fair to refuse?

- Fine to park here?

- Enter the Bowen reforms

- Home grown

- Limited partnerships: a new breed

- Salvesen fallout: the latest round

- Gambling in football – the Scottish perspective

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Changing sides

- Business drivers

- CCBE comes to Edinburgh

- "Find a solicitor" gets an upgrade

- Law reform roundup

- Thoughts on a frenetic year

- Check those bank instructions

- Fraud alert – ongoing bank frauds identified

- AML: sizing up the risk

- Master Policy Renewal: what you need to know

- Without prejudice

- What's the measure of a ruler?

- Ask Ash