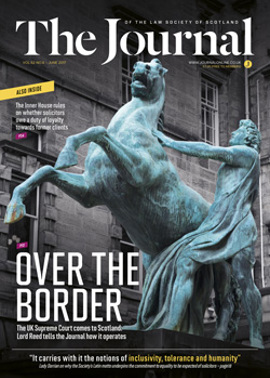

Court of the nations

History in the making? It may not be about to reshape human destiny, but this month’s sitting in Edinburgh of the UK Supreme Court can fairly be described as a groundbreaking move that could do much to improve the public perception, and understanding, of the court.

“I think we all feel it’s an important development,” Lord Reed, one of the two Scottish Justices on the court, told the Journal. “We’re conscious that we are a UK institution for the whole of the UK, and there has been criticism in the past of our being based in London and not being perceived at any rate to be sufficiently involved in the other jurisdictions, so we’re looking forward very much to being in Edinburgh.”

The initiative was floated publicly in an address last November by the current President, Lord Neuberger, entitled “The Role of the Supreme Court Seven Years On,” when he expressed the desire to see the court hearing appeals in Edinburgh, Cardiff and Belfast. With the next largest number of appeals after England, Scotland has been chosen for a test venture, but Reed and his colleagues hope that a successful mission will be followed by similar visits to the other home nation capitals.

It is certainly unusual for a court of final appeal to vary its location in this way – the only precedent Reed can think of is his own court constituted as the Privy Council, which on occasion is invited to one of the Commonwealth jurisdictions from which it still hears appeals, as recently with the Bahamas. But the court is aware of the national sensitivities within the UK – which certain Scottish politicians have previously played on when a decision unwelcome to them was handed down – and its members collectively are keen to increase public understanding of its role and the way it works.

Watch, and understand

Much has already been achieved through an award-winning communications team, and importantly through the court’s embracing of IT. Hearings, and delivery of judgments, are live-streamed over the internet, and can be accessed for about a year after judgment is given, all via www.supremecourt.uk. But while that makes a difference, Reed comments: “I think there’s nothing quite like sitting in Edinburgh or Belfast or Cardiff for people there to think of the court as their court as well as being a London court.”

The benefits of paying attention to the court’s public image became the more apparent with the Miller case on the exercise of the prerogative to trigger the official Brexit process. “If you think what the reaction was to the Divisional Court judgment in that case,” Reed observes, referring to the “Enemies of the People” headline and similar comment, “that was a decision that came as it were out of the blue. People had known there was a case in court but they hadn’t known what was going on in the court until the judgment was issued”.

Ahead of the appeal, press coverage was frequently based on a premise that the judges would decide the case according to their personal views on Brexit. In the event, “First of all, a very large number of people watched it online, about 300,000 of them, and more saw excerpts on television, and what they realised was that the case was not a discussion of whether Brexit was a good thing or a bad thing; that simply didn’t feature: it was a very intense focus on quite a technical point of law on the interpretation of the 1972 Act and the authorities on the scope of the royal prerogative. The feedback was that people found it reassuring that we were engaged as judges on a difficult technical legal point which was being heard in a measured and courteous atmosphere, and obviously being considered with care. And so when the judgment came out the coverage was very different from that of the Divisional Court judgment.”

He believes this was essentially because “People realised that this wasn’t activist judges second-guessing the politicians, but judges deciding a difficult point of constitutional law. That was only possible because journalists and politicians could actually see for themselves what was going on.”

Moving on from the Lords

At the time the court was created there was some level of assumption that it was just an exercise in reconstituting the Appellate Committee of the House of Lords. But the new court has made rather more impact than that. Is it actually very different in character?

“There have been quite a lot of significant changes, generally for the better,” Reed responds. “I don’t think they have altered at the end of the day what the court does, what its function is or its constitutional role, or indeed the way cases get decided in terms of their outcome, but it gave us the opportunity to rethink quite a lot of matters, including how we present ourselves to the public, and so things like broadcasting, public access, the educational aspects of what we do, those have all changed very considerably from the House of Lords.”

This has given the court its own “institutional character”, separate from Parliament, enabling it to create “a welcoming, friendly atmosphere”. Further, “The facilities that we have are very much better, and the use that we make of technology, particularly IT, is greatly improved. We have more space, more judicial assistants and other legal scholars who sometimes spend time with us, and that has enabled us to have effectively a bigger research staff helping the Justices; and the facility to be in contact with each other, having lunch together every day, all being in close proximity in our rooms, and using email a great deal, means that the way we go about preparing judgments has altered from what I’m told in the days of the House of Lords.”

Whereas then, each judge would go off to write their own speech, even if only a concurrence, and then circulate it for (probably limited) comment, “now we make much more use of single or joint judgments; the process of preparing judgments involves a lot of feedback from colleagues via email, and so the court is operating in a more collaborative way than it used to do”.

Some have gone further, and suggested that its very name has given the court a tendency to be more assertive, particularly in ruling on public law matters such as the extent of Government powers.

Reed doubts this. “The proportion of appeals that succeed is much the same as it used to be; the number of cases that the Government win and lose has remained much the same; and our role in the constitution is the same, so I don’t think that’s borne out by the statistics, and I don’t think it’s my impression either.” He suggests that in recent decades, judicial activism in public law reached its high water mark in the mid-60s to early 70s, with cases like Ridge v Baldwin, Conway v Rimmer, Anisminic and Burmah Oil, then a less active period followed until a further surge in the latter days of the House of Lords under Lords Bingham and Hoffmann. “Currently I think from a metaphorical perspective this isn’t an especially active period in that field of public law. We do have a lot of public law cases, and the Government wins some of them; it loses some of them.”

The limits of supremacy

In his November 2016 address already referred to, Lord Neuberger argued that “the very fact that we have parliamentary sovereignty and we do not have a formal overriding constitution could be said to prevent the UK Supreme Court being a normal common law supreme court, let alone a civilian constitutional court”. What comparisons might he have been drawing in the common law context?

“I suppose he may well have had in mind the US and Canada,” Reed observes. “Also when we sit as the Privy Council we are sitting quite often as a final constitutional court operating a written constitution, and in the exercise of that jurisdiction we are very often assessing whether legislation is constitutional or not, and it’s a very different exercise from the one we undertake as the Supreme Court.”

He goes on: “Obviously there are issues that you can tackle in this court that you can also tackle in a supreme court, but you go about it in a different way. For example at the moment I’m working on a case to do with court fees, and whether the fees have been set at a level that prevents the right of access to justice from being exercised. Now a Canadian court would come at that through the Canadian constitution and the right of access to justice. We come at it from the common law, and insofar as the fees have a legal basis in an Act of Parliament that obviously affects our analysis and means there are limits to what we can do in a way that wouldn’t apply in a jurisdiction where you had a written constitution such as Canada. If that’s what Lord Neuberger had in mind, I would certainly agree with him. The absence of a constitution does set limits to what this court can do.”

Cases at the top level

Not only is it well resourced; the court is also selective over which cases it hears, and will then subject those to a very rigorous analysis. An example that comes to mind is last year’s appeal on the Scottish Government’s “named person” scheme, and the treatment given to the human rights issues raised. How different is it from sitting in the Inner House, as Reed did before his current appointment?

“Yes, it is a different exercise,” he accepts. “We look at far, far fewer cases, and we or the lower courts themselves only grant permission for a case to come here if we think it raises an arguable point of general public importance. When we do hear a case because of its importance, first of all we quite often have interventions from parties who weren’t represented in the courts below (the named person case is an example); also you might get the Advocate General, for example, taking part in proceedings here, when they haven’t taken part below, and you may get different representation – the Lord Advocate for example will quite often appear in our court when he hadn’t in the Inner House. For all these reasons you quite often get a different, and richer, legal argument presented from the one presented to the lower court.

“Usually the parties will place before us a good deal of comparative material from other jurisdictions, which may not have been before the courts below, and we will research a case ourselves very thoroughly, because we have the time and resources available to us to do that. We will also have more judges looking at it than in the Inner House or Court of Appeal; they will be more diverse in background, because they won’t be all Scottish or English, and with different sorts of professional experience. So one of the reasons for our existing is that we should be able, through the care that both the lawyers appearing before us and ourselves are able to devote to a small number of important cases, to add value to the judicial consideration of those cases above and beyond what was achieved by the lower appellate court.”

Is there any danger of the court being too selective in what it decides to accept for hearing, and thereby restrict access to justice for some?

“We try to guard against that. First of all, it’s possible for permission to be granted by the court below, and in practice, of the cases that we hear, permission is quite often being granted in Edinburgh rather than by us. For the rest, the ones that do come here, we have a panel of three Justices normally to look at each application for permission, and the practice is that if any of the Justices feels that the case is arguable and raises an important point, then permission will be granted. It’s not done by majority vote. And the panels are quite diverse. This afternoon I’m going to be considering a whole group with Lord Kerr from Northern Ireland and Lord Hughes, an English judge, so it’s a bit like a joke about an Irishman, a Scotsman and an Englishman. We’ve got different backgrounds: Lord Hughes is a family and criminal judge, my background is more commercial and public law, and Lord Kerr is really a public lawyer. If none of us think the case ought to come here then it won’t, but if any of us does, then it will. So we do have safeguards built into the system.”

Until recently the Scottish rules did not in general require judicial permission for an appeal to be taken, and Reed in particular was quite critical of the court’s time being taken up by cases that had little prospect of success. That was changed by the Courts Reform (Scotland) Act 2014 so that similar rules now apply as in England. Are the right cases getting through as a result?

“Yes, I think so. What we’re finding now is that the rate at which we are granting applications is one third, and that’s the same for Scotland as for England & Wales – it’s been a constant rate for their cases for a number of years now. And the rate at which we allow appeals is more or less the same now for Scotland as for England & Wales: for Scotland it’s slightly below 50%; for England & Wales it’s slightly above 50%. In the past, the Scottish rate was different because we were getting a number of appeals that really had little merit in them, the ones that counsel was certifying where the court wouldn’t have granted permission.”

Ongoing change

During their week in Edinburgh, some of the judges will find time to take part in a panel session at the Law Society of Scotland, on what the future holds for the court, with reference in particular to the impact of technology. While the court has already forged ahead in its use of IT, Reed, who sits on its IT committee, mentions two further recommendations being put in hand.

“One is that we should cut down very considerably on the use of paper for authorities. We get enormous bundles of authorities, as indeed does the Inner House, and it costs a great deal of money for these things to be produced. We now get our authorities in the form of a pen drive, and the idea that we’re suggesting is that we should do away with all paper authorities other than one bundle of core authorities, and for the rest simply use a pen drive and have laptops in court. It requires of course all the judges to be comfortable using laptops in court, and counsel also. We’ve had a programme of training for all the Justices so we’re now all up to speed, and we have a liaison committee with court users through which we’re pursuing discussions with the bar to see if we can introduce this sooner rather than later.

“The other is in our Privy Council jurisdiction. We traditionally have had the lawyers come to London to argue the case, unless we go and hear it in the local jurisdiction ourselves. What we’ve been looking at is the use of video links to hear appeals in that way. So far I think we’ve had one oral hearing of a permission to appeal application, and we’ve got an actual appeal hearing listed to take place between now and the end of July. What we’re thinking is that we can use this technology in order to reduce the cost of using the court and make it more convenient. With the Privy Council, there is an issue about time differences: the forthcoming appeal is from one of the Caribbean jurisdictions, and the plan is for us to hear the appeal in the afternoon for us, which will be the morning their time. If this works out, and the permission hearing did work well – despite the technology there was quite an easy dialogue between the judges and counsel – if this works well we’ll take that further.”

But for this month, it is physical presence that is the innovation, with seven of the 11 Justices coming to Edinburgh – Lord Neuberger, Lady Hale, Lord Reed, Lord Hodge, Lord Mance, Lord Clarke and Lord Kerr. The three appeals scheduled will be heard as this magazine is being printed, hopefully adding a few more bricks to the edifice of public understanding of the law, and of the role of the UK Supreme Court.

Three for the panel

Three Scottish appeals are being heard by the Supreme Court over the four days of its sitting in Edinburgh:

Sadovska v Secretary of State for the Home Department will consider the evidential burden on the state when disrupting “sham marriages”;

Aberdeen City and Shire Strategic Development Planning Authority v Elsick Development Co Ltd relates to the correct legal test to be applied when assessing planning obligations, and the extent to which planning authorities are bound to comply with national planning policy; and

Brown v The Scottish Ministers concerns the obligation on the state to assist the rehabilitation of determinate sentence prisoners.

A panel of five judges is sitting to hear each appeal, with the President, Lord Neuberger, presiding. The Lord President of the Court of Session, Lord Carloway, is a member of the panel hearing the appeal in Brown.

In this issue

- Neutrality policies in commercial companies

- Court IT: the young lawyers' view

- Human rights: answering to the UN

- Galo and fair trial: which way for Scotland?

- Secondary victims in clinical negligence

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion: Alan W Robertson

- Book reviews

- Profile

- President's column

- Twin tracks to completion

- People on the move

- Court of the nations

- Second time around

- How to avoid a summer tax scorcher

- Humani nihil alienum: a call to equality

- Sheriff commercial procedure: count 10

- Taking a pay cut: fair to refuse?

- Fine to park here?

- Enter the Bowen reforms

- Home grown

- Limited partnerships: a new breed

- Salvesen fallout: the latest round

- Gambling in football – the Scottish perspective

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Changing sides

- Business drivers

- CCBE comes to Edinburgh

- "Find a solicitor" gets an upgrade

- Law reform roundup

- Thoughts on a frenetic year

- Check those bank instructions

- Fraud alert – ongoing bank frauds identified

- AML: sizing up the risk

- Master Policy Renewal: what you need to know

- Without prejudice

- What's the measure of a ruler?

- Ask Ash