Enter the Bowen reforms

Sheriff and jury reforms

Sometimes the wheels of law reform grind slowly, but, after seven years, sheriff and jury procedures are being updated.

After the early success of the Bonomy reforms, introduced in 2004 to improve High Court procedures, it soon became clear that sheriff and jury procedures were falling behind. In June 2010, Sheriff Principal Bowen produced the Independent Review of Sheriff and Jury Procedure, which lifted improvements from Lord Bonomy’s changes and suggested other recommendations to suit this forum where many more cases are dealt with. These were well received and eventually included in a Criminal Justice Bill, but this was delayed due to the more controversial proposal to abolish corroboration. Finally the Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 2016 was granted Royal Assent in January 2016. Since then there have been frequent delays due to the need to plan implementation.

The main change is that, like High Court indictments, the Crown will no longer set the trial diet, and no witnesses will be cited until parties are ready for trial. This should be of great help to witnesses who are often festooned with various citations until the trial gets underway.

Part 3 of the 2016 Act, dealing with solemn procedure, has come into operation on different dates. Judicial examination in new cases was abolished from 17 January this year, when minor changes in relation to preliminary hearings and guilty pleas on behalf of organisations also came into effect. Under Commencement Order No 4 (SSI 2017/99), from 29 May 2017 changes to custody and bail time limits apply, the requirement to lodge a written record is now governed by s 80 of the Act (new s 71C of the 1995 Act) and the Act of Adjournal, in place of the Lord Justice General’s Practice Note no 3 of 2015, and the Crown will begin to indict cases to a first diet only during a transitional phase to the end of August. The aspiration is that when the indictment is served, the defence will have notice of everything necessary to settle the case or finalise preparations. Police ought to have all statements in the hands of the Crown 21 days after full committal, but accident reconstruction, drugs statements of opinion and specialist reports will inevitably take longer. The indictment should list all witnesses, documentary and labelled productions. In the recent past, the court has been bedevilled by skeleton indictments containing only the charges and a few witnesses, with evidence following in a stream of s 67 notices and late disclosure.

The induciae between service of the indictment and the first diet is increased from 15 to 29 days. Defence statements must be served 14 days before the first diet, and not lodged at the bar as has often occurred. Parties should have meaningful communication well in advance of the first diet, and any preliminary pleas or special defences should be lodged two days before. In bail cases this diet is to commence within 11 months of first appearance, and in custody cases within 110 days of full committal. Assuming parties are ready, trial will be fixed within one month of the first diet and this date will “float” for four working days before the case requires to call and further procedure be discussed.

For custody cases the time limit for commencing trial has been extended from 110 to 140 days, in line with High Court cases. Responsibility for fixing trial diets will pass to the court; systems will be in place for it to have early warning of levels of business so that sufficient time can be allocated within the sheriffdom.

Where bail is opposed, agents will no doubt impress on the court the possibility of the accused being remanded for longer than previously. Hopefully in time electronic monitoring will supplant the existing curfew system, which cannot be properly policed but on the other hand can prove arduous for family and friends providing a bail domicile, who are regularly woken by police checking on the accused.

While the Bonomy changes were initially successful and continue to be helpful to witnesses by cutting down on trial citations, it has been disappointing to see the 140-day limit ignored in many High Court cases and accused spending a year or more in custody prior to trial. It is to be hoped this will not arise in the sheriff and jury court, but in recent years – despite increased sheriff summary sentencing powers – greater recourse has been made to indictment procedure. As Audit Scotland pointed out in its recent review of summary prosecution, solemn cases have increased from about 5,000 per annum to 8,000 despite falling crime rates. Crown preparation has often suffered as a result, and many cases have proved not to be of the requisite standard.

A smaller, better prepared cohort of cases, backed up by close shrieval oversight and tight court management, will be required to make these long overdue changes a success.

Desertion simpliciter

The Appeal Court reiterated the high test which the court has to deploy under HM Advocate v Fleming 2005 JC 291 before desertion simpliciter is appropriate.

In HM Advocate v Donaldson [2017] HCJAC 29 (decision dated 20 November 2015) the respondent faced an indictment containing 16 charges of assault, breach of the peace, assault to injury and danger of life and contraventions of the ubiquitous s 38(1) of the Criminal Justice and Licensing (Scotland) Act 2010. Petition proceedings commenced in December 2013 with nine charges. The respondent was indicted to a first diet in November 2014 but trial was postponed until March 2015, and again until May 2015, to allow the defence more time to prepare, with extensions to the time bar. It was thought the Crown held certain records but these remained with police, and the case was deserted pro loco et tempore and the time bar extended to 31 August. A fresh indictment with seven additional charges was served. The Crown had received the additional disclosable material on a pen drive but required to consider it and redact certain information. The sheriff refused more time to do this and deserted the case simpliciter. He highlighted the Crown’s repeated failures to disclose and that the case would have required a fourth extension. The High Court disagreed, as the standard to be deployed was whether a fair trial had become impossible. An order should have been placed on the Crown (or other haver) to disclose the records; this would have reduced first diet churn and brought matters to a head earlier. An extension was granted to allow the material now available to be disclosed and the defence prepared. Let us hope the new Bowen procedures avoid such sagas in future!

Video evidence: Full bench ordered

In the appeal against conviction by Gubinas and Radavicius v HM Advocate [2017] HCJAC 25 (9 May 2017) the court had to consider video footage taken on mobile phones when the appellants were engaged in sexual activity with the complainer. The argument was whether it showed criminal or consensual behaviour.

In cases where identification is in dispute the jury are directed to consider the evidence given by witnesses speaking to the video recording and decide whether they believe the identifications made or evidence to the contrary. It is not for the jury to investigate the footage and reach their own conclusions. The Appeal Court noted that in relation to directions regarding what video evidence depicts, the law is not clear (Renton & Brown’s Criminal Procedure, para 24-158.3). In some cases such as those involving professional shoplifting gangs, the jury may require an explanation of what the footage shows to determine the culpability or otherwise of those involved; in other cases the circumstances shown may be eloquent of guilt to a greater or lesser extent. In light of the increase in video evidence since 2000 and the state of uncertainty, the court resolved to remit the point to a larger bench.

Moorov again!

In the latest reported case a 17-year gap between the charges spoken to by two complainers was held to be too long to support the need to show a course of conduct.

In RB v HM Advocate [2017] HCJAC 24 (28 April 2017) the appellant had been the schoolteacher of both complainers when lewd behaviour was alleged. The second complainer was the nephew of the first; the appellant became acquainted with him as a family friend. By contrast the first complainer met the appellant when he started secondary school.

The Appeal Court repeated that in the Moorov context the search is always for an underlying unity of intent such as to indicate a course of conduct on the part of the accused. The court has stressed the need for evidence that the individual incidents are not unrelated but are component parts of one course of conduct persistently pursued by the accused. In RB’s case there was no link such as occurs where the accused is related to both complainers and similar conduct is committed against complainers from different generations. The rule of mutual corroboration must be approached with caution when there are only two complainers. There was a 17-year gap and the family connection was not a powerful factor. The court was of the view that the trial judge should have withdrawn the case from the jury, and quashed the convictions.

Directions on matter not raised

In many trials, the defence chooses to offer the jury the stark choice between conviction of the crime charged or acquittal, and indeed the Crown similarly presents the case on an all-or-nothing basis when a halfway house verdict such as culpable homicide or guilty under provocation may be proper alternatives on the evidence. The old school of judging, represented in Mackay v HM Advocate 2008 SCCR 371, was that the content of the judge’s charge was fenced in by the way the case was presented by parties and limited to the issues raised.

In Kukanauza v HM Advocate [2017] HCJAC 26 (12 May 2017) the appellant was charged with rape. The judge in his charge raised with the jury the alternative charge of attempted rape although it had not been referred to in either speech. The Appeal Court reiterated the correct approach following Ferguson v HM Advocate 2009 SCCR 78, that if the judge is considering directing the jury on an obvious alternative verdict reasonably available on the evidence, this should be communicated to parties outwith the presence of the jury before speeches so as to avoid any possible unfairness. In the present case, no miscarriage of justice took place in light of the evidence and the appeal was refused.

Second level of appeal

An appeal from the Sheriff Appeal Court to the High Court will only take place in limited circumstances when leave is granted.

In Stolarczyk v HM Advocate [2017] HCJAC 23 (30 March 2017) the appellant had been convicted of assaulting his former partner by pushing her, causing her to fall to her injury. Evidence was led from the complainer and a police officer who spoke to a statement in which the appellant said he had taken the complainer’s mobile, she wanted to grab it back and he pushed her away, she turned and fell on the radiator but it was her own intention and he hadn’t pushed her enough for her to fall. He claimed he was attacked and was defending himself. The sheriff rejected the qualifications in the appellant’s statement and convicted him on the basis that self-defence was not made out. The High Court was of the view that the Sheriff Appeal Court had mistaken the case as an appeal against a submission of no case to answer when no such submission had been made. The statement was not a mixed one; in any event the sheriff was entitled to reject the qualifications. He was then left with an admission evidencing an unjustified physical attack on the complainer. The appeal was refused.

Don't bring a stun gun home!

Lords Brodie and Turnbull refused an appeal in Morton v HM Advocate [2017] HCJAC 21 (12 April 2017), where the judge had imposed the statutory minimum of five years’ imprisonment for bringing two stun guns back from holiday in Bulgaria. The guns were disguised to look like mobile phones. It was submitted the appellant had special family circumstances; two of his four children attended a special school. His intention in bringing the guns home was to sell them for £300 each. In light of those intentions and the intention of Parliament to punish those involved in the importation of such devices, deemed to be firearms,

with a significant sentence unless there were exceptional circumstances, the appeal was refused

In this issue

- Neutrality policies in commercial companies

- Court IT: the young lawyers' view

- Human rights: answering to the UN

- Galo and fair trial: which way for Scotland?

- Secondary victims in clinical negligence

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion: Alan W Robertson

- Book reviews

- Profile

- President's column

- Twin tracks to completion

- People on the move

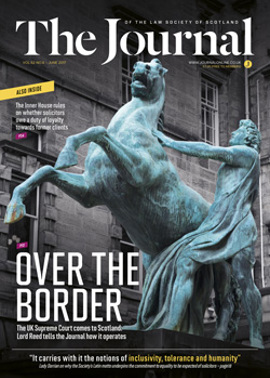

- Court of the nations

- Second time around

- How to avoid a summer tax scorcher

- Humani nihil alienum: a call to equality

- Sheriff commercial procedure: count 10

- Taking a pay cut: fair to refuse?

- Fine to park here?

- Enter the Bowen reforms

- Home grown

- Limited partnerships: a new breed

- Salvesen fallout: the latest round

- Gambling in football – the Scottish perspective

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Changing sides

- Business drivers

- CCBE comes to Edinburgh

- "Find a solicitor" gets an upgrade

- Law reform roundup

- Thoughts on a frenetic year

- Check those bank instructions

- Fraud alert – ongoing bank frauds identified

- AML: sizing up the risk

- Master Policy Renewal: what you need to know

- Without prejudice

- What's the measure of a ruler?

- Ask Ash