Fine to park here?

As a discipline, law is full of many attractive simplifications that can unravel on closer analysis. For example, everyone knows there is no law of trespass in Scotland, right? It can be said with some confidence that a one-time bare trespasser, causing no damage to property, will not normally incur civil liability to a landowner. In criminal law terms, signs proclaiming “Trespassers will be prosecuted” are doubly ineffective in Scotland: there is no criminal liability for bare trespass, assuming access is not otherwise restricted, as with a railway line; and a landowner’s assertion about prosecution somewhat ignores the role of procurators fiscal.

Needless to say, that is not the whole story. If everyone does have the right to stravaig wherever they want, why did Scots law develop all those rules about public rights of way and servitudes? And while the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003 has undoubtedly liberalised the regime for responsible access, it does not provide carte blanche to access takers. In fact, a 19th century dictum that it is “loose and inaccurate” to say there is no law of trespass in Scotland (Lord Trayner in Wood v North British Railway (1899) 2 F 1 at 2) has recently received approval in the Court of Session (Lord Turnbull, Scottish Parliamentary Corporate Body v The Sovereign Indigenous Peoples of Scotland [2016] CSOH 65 (particularly paras 31-33), affirmed [2016] CSIH 81, analysed by Combe, “The Indycamp: Demonstrating Access to Land and Access to Justice” (2017) 21 Edin LR 228-233). So much for that pithy but deceptive simplification.

Another attractive and slightly related simplification that has developed is that private parking schemes are unenforceable in Scotland. Indeed, in the relatively recent past, the writer encouraged an acquaintance to pay little heed to an “enforcement” letter received from an operator of a pay-to-park scheme on open ground. My confidence stemmed from two factors. First, I was assured that the signage around where the car was parked was unclear, thus a contract on the terms claimed could not have been validly entered into. (Matters would have been different with a scheme where access is taken via an automated or manually operated barrier, with terms being made clear on entry, on a take it or literally leave it basis.) Secondly, the operator’s standard letter made copious reference to enforcement by way of bailiffs and/or the court system of England & Wales. (Naturally, this would not have affected whether there was liability, although it did strike me as potentially relevant to the likelihood of actual and appropriate process being followed.) As it transpired, the letter was duly ignored and nothing more came of it.

If that anecdote suggests that private parking schemes can be unenforceable, so too perhaps does the fact that Scots law does not allow one tool of the trade to function. In some jurisdictions, such as South Africa, it is not uncommon to see signage that says vehicles parked without permission will be clamped until a release fee is paid. But Scots criminal law says clamping a car then requesting a release fee is classed as extortion (Carmichael v Black 1992 SLT 897). (Similar rules now prevail in England, after the Protection of Freedoms Act 2012.)

That scene-set suggests that parking operators in Scotland might have a difficult time of it, and until recently that seemed to be the situation (see White, “Parking’s fine: the enforceability of ‘private’ parking schemes” 2007 Jur Rev 1). But two important recent cases clarify that landowners can ensure (by themselves or an agent) that those who park on their land will be governed by certain obligations, including the possible need to pay a fee. Those cases are ParkingEye v Beavis [2015] UKSC 67 and Vehicle Control Services Ltd v Mackie [2017] SC DUN 24.

Charging in court

In ParkingEye (and the linked case of Cavendish v El Makdessi) seven Justices of the UK Supreme Court wrestled with the enforceability of penalties, as applied in a private parking scheme. Simply stated, the case stemmed from Beavis parking for longer than two hours, contrary to what was stipulated on clear signage at the car park, for which he was charged £85 (in line with the signage). The Supreme Court held that there was a valid contract incorporating that term, and the term stood notwithstanding arguments about its enforceability as a penalty.

Lord Hodge offered a Scottish perspective. After elaborating the correct test for a penalty (at para 255), he held that while the test was engaged the £85 fee was acceptable, as operators had a legitimate interest to protect by imposing the parking charge, the level of which was neither exorbitant nor unconscionable (paras 284-287). Consumer protection arguments were raised based on the Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations 1999 (SI 1999/2083), which would now be governed by the Consumer Rights Act 2015, but (with Lord Toulson dissenting on this point, and Lord Hodge apparently swithering: para 289) these were held not to be an issue. The consumer group Which? – which had intervened in the case – noted it was “concerned” with the ruling.

Beavis’s transgression, if that is the correct word, was a one-off, in contrast to the more recent Vehicle Control Services case. When the defender moved in with her parents in 2013, she persistently parked in front of a garage of which her parents had the use at a complex of flats in Dundee. The site owners had (via a factoring arrangement) competently appointed the pursuer to operate a car parking scheme which required a permit. There was signage to that effect. Failure to display a permit would result in a fee of £100, which could be reduced to £60 on payment within 14 days. It was not disputed that the defender had repeatedly ignored this scheme both by parking without a permit, and parking in a designated “No Parking” area. It is clear that both the defender and her father believed the scheme was not enforceable.

While they were far from the only Scots to hold this view, Sheriff Way noted it was a misdirection as to the law. In a three-paragraph “Discussion and opinion”, he preferred the pursuer’s submissions and held that there was a contract which had been breached, and the charges were a legitimate mechanism to create a potential revenue stream that was needed to protect parking amenity. (No consumer protection point was raised.) The repeated transgressions led to a striking amount of liability, £24,500. The Telegraph has described this as “Britain’s biggest parking fine”.

Discussion

At one level, it is difficult not to feel sympathy for the defender in this case. Without wishing to make too many assumptions, the circumstances suggest a five-digit sum will not be particularly simple for her to meet. No comment is offered on whether the sum is proportionate to the administration costs, or any damage to the non-designated bay where the car was parked, but it will be recalled from Lord Hodge’s opinion in ParkingEye that that is in the nature of penalties such as this. Meanwhile, quite separately to the merits of these cases, such high-profile rulings might cause an issue with less scrupulous operators seeking to capitalise on some of the publicity, such that they would set a high fee that would fall foul of Lord Hodge’s test if litigated, in the hope that someone would pay it without challenge (this being a concern of Which?).

On the other side of the coin, the landowner has interests that can and should be recognised. The defender in Vehicle Control Services did not meaningfully take those interests into account. Making sensible use of contract law to allow parking amenity to be maintained, coupled with an income of a suitable sum of money from entitled users which also serves to deter potential free-riders, is an entirely reasonable proposition. Further, irrespective of the circumstances of this case, there are situations where car parks do cost a lot of money to maintain, particularly in rural Scotland near tourist or recreation spots, and the gung-ho attitudes to parking that could stem from such schemes being unenforceable could be equally problematic.

Other considerations?

With access to the outdoors in mind, mention should be made of the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003 for completeness. Part 1 allows for responsible access across much of Scotland’s land for certain recreational, educational and other purposes, but motorists will struggle to rely on this. First, in terms of s 9(f) motorised access will never be classified as responsible access. That said, car parking is mentioned in the Scottish Outdoor Access Code, the guidance document about the right of responsible access approved by the Scottish Parliament, under explanation that motorised activities are not covered by access rights and, as such, special consideration should be taken when leaving your car anywhere (p 76; see also p 46, para 3.58). But all of this is subject to a more fundamental problem: the right of responsible access nowhere confers a right to leave unaccompanied corporeal moveable property of any sort, never mind a car, although a logical case could be made for briefly unattended items that are actually integral to a responsibly conducted permitted activity.

Finally, it should be noted that none of the above is relevant to parking schemes operated by local authorities, which are backed by statute. As it happens, there is also a Scottish Government consultation about responsible parking, seeking views on how to address problems with pavement parking, disabled parking provision, and determining what parking incentives local authorities can provide for the uptake of ultra-low emission vehicles, which closes on 30 June 2017.

Beyond doubt

Following the decision of the Supreme Court, the law about the contractual standing of private parking schemes is now beyond doubt. Its recent application by Sheriff Way highlights its full – and potentially expensive – implications. There are questions that the legislature may need to contend with in the future, in terms of consumer protection and whether the ratcheting up of such sums of money should be allowed. Until that happens, motorists are advised to pay attention to any signage near their appointed parking place, and consider carefully whether it is fine to park there.

In this issue

- Neutrality policies in commercial companies

- Court IT: the young lawyers' view

- Human rights: answering to the UN

- Galo and fair trial: which way for Scotland?

- Secondary victims in clinical negligence

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion: Alan W Robertson

- Book reviews

- Profile

- President's column

- Twin tracks to completion

- People on the move

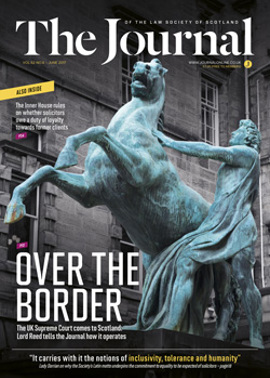

- Court of the nations

- Second time around

- How to avoid a summer tax scorcher

- Humani nihil alienum: a call to equality

- Sheriff commercial procedure: count 10

- Taking a pay cut: fair to refuse?

- Fine to park here?

- Enter the Bowen reforms

- Home grown

- Limited partnerships: a new breed

- Salvesen fallout: the latest round

- Gambling in football – the Scottish perspective

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Changing sides

- Business drivers

- CCBE comes to Edinburgh

- "Find a solicitor" gets an upgrade

- Law reform roundup

- Thoughts on a frenetic year

- Check those bank instructions

- Fraud alert – ongoing bank frauds identified

- AML: sizing up the risk

- Master Policy Renewal: what you need to know

- Without prejudice

- What's the measure of a ruler?

- Ask Ash