Humani nihil alienum: a call to equality

It is a very great pleasure to be invited to deliver this keynote address at the start of the Law Society of Scotland’s “Equality Means Business” conference. I have followed closely the Society’s work in promoting equality and diversity in the profession. The Society is to be congratulated for its excellent work in this regard, and I salute your determination to deliver real, tangible results. It is therefore a great honour to be asked to deliver this address on a subject of central and ever-pressing importance.

This is an issue which has implications not just for the accessibility and delivery of legal services in our jurisdiction, but for the very future of the profession itself.

I imagine that I might perhaps be seen to be well-qualified to deliver a keynote address on equality in the legal profession by virtue of my own career. Being one of a minority of women Senators of the College of Justice and the first woman Lord Justice Clerk of Scotland is certainly a great honour and a great privilege – and quite a surprise to me. I could recount many tales from my own experiences relevant to this address but, truth be told, I have worked hard, taken every opportunity presented to me, and, very importantly, had a good deal of luck. If my career is sometimes described as a “success story” for the role of women in our profession, that is very heartening. But the very attention given to it, and the rarity of it, suggests to me that equality remains a very pressing and concerning issue in the profession and there remains much progress to be made.

Early obstacles

Having said that, we have come a long way. According to the editors of the Stair Memorial Encyclopaedia, access to the legal profession in Scotland from the 17th century to the start of the 20th century was controlled by three factors: gender, social class and wealth.

In 1901, Miss Margaret Howie Strang Hall presented a petition to the court asking to be admitted as a member of the Incorporated Society of Law Agents. In a surprisingly enlightened approach, the Society indicated that it did not feel called upon to oppose the prayer of the petition, and that it did not conceive it to be to its interest to maintain that women ought not to be enrolled as law agents. However, there were some potential legal obstacles and it was a matter for the court to decide. The Society pointed out that in America there were women lawyers, and the heavens had not collapsed. In our own country there were women medical practitioners and women had been granted the right to sit on parish councils and to become factory inspectors, which last office was relevant because under the Factories Act inspectors could conduct complaints before courts of summary jurisdiction.

Alas, the courts were having none of it. They referred to the importance of usage and custom. They noted that the Romans had prohibited women from acting as procurators, and referred to a remark to like effect by Lord President Spottiswoode – as recently, I may say, as 1633! The court was authorised to admit “persons” to the Society, but by custom and usage, “persons” did not include women.

It was not until 1921 that Miss Madge Easton Anderson MA, LLB became the first woman in Scotland to be admitted as a solicitor; and in 1923 Miss Margaret Kidd became the first woman advocate.

At least we can say that things have improved somewhat in the last century, although I am sorry to advise you that Isabel Sinclair’s great achievement of becoming the second woman in Scotland to be made a QC, and one of only a handful in the UK, was reported in the Glasgow Herald in 1964 under the headline: “Housewife QC”.

Expression of our humanity

Anyway, we can only celebrate the fact that the solicitor population is no longer quite so one-dimensional as it once was. However, significant issues remain, not least in respect of ethnic minorities, those from less affluent backgrounds and women, who still do not attain proportionate representation at senior levels. It is thus crucial that the Society is tackling these issues head on, and events like today are vitally important in the drive to achieve real equality. The time has come to recognise that inequality will not change simply with the passage of time. Only concerted and resolute action will eliminate workplace inequality.

As someone who firmly believes in the need for the legal system, and the legal profession, to modernise, I hope you won’t brand me a hypocrite for my selection of the title for my address this morning. Humani nihil alienum is, as you will have recognised, the Society’s motto and, roughly translated, it means “Nothing human is alien to me”. I quite appreciate the move away from Latin maxims. For many, they carry overtones of elitism, and there is certainly an argument that requiring their use in professional legal practice may itself perpetuate some of the inequalities which must be eliminated: after all, Latin is now only rarely taught at school and, if it is, it tends to be at independent, fee-paying schools.

However, on occasion, a Latin maxim can serve a purpose in encapsulating an idea in a helpfully direct way. As the motto of the governing body of the solicitor branch of the profession this maxim is especially fitting, since it recognises that solicitors must be open and willing to act and to give advice across a whole range of different legal – i.e. human – affairs. It also carries with it the notions of inclusivity, tolerance and humanity, which in turn underlie the conduct, behaviours and outlook expected of Scottish solicitors. This maxim is a very fitting encapsulation to reflect the Society’s commitment to protecting and improving equality in the legal profession.

Gender issues in the profession

The evidence could not be clearer: there are real challenges facing the future of the profession in relation to its composition, access to it, and progression within it. In the UK, we know that girls perform better than boys in schools and higher education, but this does not translate into workplace success. This could not be more apposite than in the law. Nearly three quarters of all Scottish law students are female, and women account for two thirds of all solicitors under the age of 45. And yet, although women make up 51% overall of all Scottish solicitors, men are three times more likely to become equity partners than females. Solicitor advocates are almost three times as likely to be male. Even in in-house roles, director level solicitors are more than twice as likely to be male. Differences in pay become marked for those aged 36 and upwards, and after five years following qualification. Overall, there remains a 42% gap in earnings between male and female solicitors, which far exceeds the overall UK figure at 18.1% in 2016. These statistics are striking and concerning and cannot be allowed to continue in a modern legal profession.

The Society’s research into the “Profile of the Profession”, from which some of these statistics came, showed the extent to which women were less likely to be equity partners, consultants or directors; and showed how men’s careers tended to move forward at a faster rate than women’s after 10 years’ post-qualification experience, whether in private practice or in-house. The research also found, perhaps unsurprisingly given the statistics just quoted, that there had been a steady flow of women out of private practice and into in-house roles, driven largely by the inflexibility of working practices in the private sector, with the indicators being that the more flexible firms can be with working practices and options for career breaks, the better the chance of holding on to, and encouraging, their serious female talent. Other major factors identified were pay and the lack of opportunities for career development: not surprising when one considers the point just made about the gender gaps in pay and prospects of advancement.

Pre-empting the legislative change from April this year, the Society’s Head of Education, Rob Marrs, suggested firms might conduct an equal pay audit, asking the telling question: if you were accidentally to email the whole office a spreadsheet of everyone’s earnings, could you look them all in the face?

One can only imagine the uproar!

Wider access issues

Whatever the results, the statistics are highly concerning and the position cannot continue in a modern civilised society which expects and deserves equality and diversity. I know that the Society recognises this, and that it has taken considerable steps to tackle inequality in the profession.

These steps include an Equal Pay Toolkit, and Equality guides, directed towards creating opportunities within the profession and closing the gender gap. The Society has also published a document on the important subject of creating more accessible services: these are documents of the highest quality, tackling serious issues seriously, and from a properly researched baseline.

As well as being concerned about issues of equality within the profession, there remain concerns about access to the profession by those from less affluent and other minority backgrounds: I know that the Society is actively engaged with this, and it is one of several issues addressed in the Creating Opportunities Equality Guide. Whilst men have traditionally been well represented at the higher levels of the profession, it is also true that the difficulties faced by women in translating academic results into workplace success are common to those from less affluent backgrounds and other minority groups.

Similar issues arise in relation to representation of minority groups, which also lags behind the expectations of a modern society. For instance, in its research into the profile of the profession, the Society found that only 2% of respondents reported being one of the other named faiths (Muslim, Buddhist, Sikh, Jewish or Hindu). The experience of that group in terms of career progression was similar to that of women. Further, discrimination and bullying were more likely to be encountered by women and minority groups, including LGBT respondents, those with disabilities, ethnic minorities, and those from minority religions, faiths or beliefs. The Society has sought to raise awareness and to tackle these issues by issuing guidance on Preventing Bullying and Harassment and in Preventing Unconscious Bias in recruitment, steps which should be highly commended.

Why are equality and diversity so important?

To answer this question, it is important to remind ourselves of the vital role which solicitors play in our society. Solicitors provide essential support and assistance across the full cross-section of society, be that in protecting the rights of the vulnerable or supporting business and promoting the growth of the economy.

I have quoted elsewhere Chief Justice Warren E Burger of the United States Supreme Court who, in a speech on the role of lawyers in a modern society, described the role of lawyers in its highest conception: “Lawyers and judges will be necessary components wherever men and women are gathered together in villages, towns, and cities where they must rub shoulders, share boundaries, and deal with each other daily. Lawyers will be necessary because, in their highest role, they are the healers of conflicts and they can provide the lubricants that permit the diverse parts of a social order to function with a minimum of friction.”

This aptly and pointedly illustrates the role of lawyers who, in assisting in all manner of human problems and conflicts, for all manner of people from different areas across society, promote both social cohesion and economic growth. This understanding of the lawyer’s role reflects entirely the Society’s motto – Humani nihil alienum. It is no wonder then that Sam Okudjetoa, a former President of the Law Society of Ghana, said that all lawyers must understand that they are not just business people, they must think of themselves as instruments of justice.

In our busy offices, amidst the clutter of papers, the ticking of the time-recording clock and the ringing of the telephone, it is all too easy to overlook this fundamental and essential role which we perform in our professional lives every day. Dick the Butcher sought to inspire his rebel band of pretenders: “The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers,” and no doubt that would have been supported by some even today, but the reality is that this would have been to destroy a – perhaps the most – fundamental pillar of protection in securing access to justice.

So, solicitors operate at the very heart of a successful, fair and civilised society. But the profession will only really be able to continue to deliver expert impartial advice and representation if it is truly representative of the society which it serves.

In the modern age, are we really prepared to tolerate the notion that those who do not enjoy early advantages in life, or who do not come from a particular background or persuasion, should be denied the opportunity to serve society in this role of fundamental importance? The desirability of diversity and the value which it brings cannot be overestimated. In the long-term interests of the profession, we simply cannot continue to ignore impediments to access to the profession or progress within it. We cannot continue to turn a blind eye to gender, race and class imbalance in the profession. That is not to say that solicitors from the traditional majority groups cannot properly represent the interests of all society, but it is undeniable that the profession as a whole should be representative of the society which it serves, particularly in our globalised world where the composition of society itself is ever changing. If it does not do so, the profession will be diminished both in relevance and respect.

Equality and delivery

As I touched on at the Law Society of Scotland conference last year, the benefits of putting issues of equality and diversity at the heart of the profession come not just from doing the right thing: they have been recognised as essential by Parliament and are enshrined in statute with public authorities and employers now bound by certain equality duties. Indeed, public authorities translate their public equality duty into their procurement exercises. Private companies or organisations competing for business with public bodies are often required to do likewise, demanding clear commitments to equality and diversity from those whom they engage professionally, and the observation of certain minimum standards. Equality and diversity are commonly a key feature in public procurement exercises.

Furthermore, economists have also now turned their attention to gender equality and have argued that progress in this area could boost global GDP by $12 trillion by 2025. Something which may appeal to some of the equity partners in Scottish law firms!

But, joking aside, the topic of this conference is “Equality Means Business”. It is undeniable that in our globalised world, attracting, cultivating and supporting talent across a truly diverse workforce can create business value for clients, and that is why equality means business. It simply does not make any business sense to have employees working at undercapacity or not being supported to reach their full potential. Supporting all employees – not just white, middle-class, conservative males – to reach their full potential will make for a happy, fulfilled, loyal, engaged, stimulated and productive workforce.

It must also be recognised that the practice areas of the law are increasingly diverse. Not all solicitors wish to work in the same practice area, or indeed have the specialist skills for a particular practice area. Too much homogeneity within the profession runs the risk that not all practice areas, especially those which may be poorly paid, poorly funded, or unpopular, will be adequately provided for. To ensure that the needs of these areas are met, and to secure necessary legal protections, the profession must remain open to everyone, and attract solicitors of different types. The range of services which the profession requires to provide is diverse, the client base you are expected to serve equally so: what these all demand is a profession which is just as diverse and which is truly reflective of the society which it serves. In other words, the need for a profession which can truly deliver upon the maxim Humani nihil alienum is as pressing as it ever has been. Let us make no mistake: equality within the profession is inextricably bound up with access to justice and delivery of legal services; the need for a diverse and truly reflective profession cannot be divorced from it.

The next challenges

That last observation takes me on to my next point: how do we – the present-day custodians of the profession – secure diversity in the years to come? It is by following the Society’s lead: by taking equality and diversity issues seriously, by implementing and heeding the Society’s guidance and by welcoming and sponsoring new and prospective entrants who do not come from the conventional groups of the past.

It is also by recognising another type of inequality, namely generational inequality. We will all of us be aware of the particular difficulties which the young of today face: younger people are suffering a greater drop in income and employment compared to older age groups and now face greater barriers to achieving economic independence and success. In law, these issues are acute: university tuition fees and student debt; massive competition for traineeships; and the difficulties in obtaining the first qualified post which will set them on their future career.

So, reflecting on the issues in our society today, it is vitally important for the profession, and the security of its future, that obligations of training, sponsorship and nurturing career development are taken seriously. There are obligations upon those who have enjoyed the profession, who take pride in it, and who perhaps have done well from it, to assist in securing a sound and solid future for coming generations.

These young lawyers – who are, after all, the future of the profession and its place at the heart of society – must be able to develop their own aspirations and ambitions, helping them in due course to assume the mantle as custodians of a profession of which they, and our wider society, can be proud. It is crucial that the spirit of support and respect, from which older members of the profession have benefited, is entrenched and continued for the good of the profession in the years to come.

A successful and respected legal profession must reflect the society it serves. It will only do that if it leads the way in meeting contemporary expectations (indeed, formal legal obligations) on equality and diversity. It is vitally important that the profession places itself in the best position to benefit from the widest possible talent pool and that such talent is recognised and retained in the profession. Only a profession truly and realistically open to all can properly respond to and deliver upon the diverse legal services needs of our modern society. In working towards and achieving true equality and diversity, the society’s motto is more relevant than ever. Equality is really about a common regard and respect for all humanity: we will know that true equality has been achieved when we can honestly say: Nothing human is alien to us.

In this issue

- Neutrality policies in commercial companies

- Court IT: the young lawyers' view

- Human rights: answering to the UN

- Galo and fair trial: which way for Scotland?

- Secondary victims in clinical negligence

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion: Alan W Robertson

- Book reviews

- Profile

- President's column

- Twin tracks to completion

- People on the move

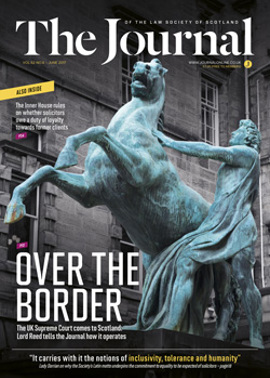

- Court of the nations

- Second time around

- How to avoid a summer tax scorcher

- Humani nihil alienum: a call to equality

- Sheriff commercial procedure: count 10

- Taking a pay cut: fair to refuse?

- Fine to park here?

- Enter the Bowen reforms

- Home grown

- Limited partnerships: a new breed

- Salvesen fallout: the latest round

- Gambling in football – the Scottish perspective

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Changing sides

- Business drivers

- CCBE comes to Edinburgh

- "Find a solicitor" gets an upgrade

- Law reform roundup

- Thoughts on a frenetic year

- Check those bank instructions

- Fraud alert – ongoing bank frauds identified

- AML: sizing up the risk

- Master Policy Renewal: what you need to know

- Without prejudice

- What's the measure of a ruler?

- Ask Ash