Neutrality policies in commercial companies

On 14 March 2017 the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) gave further consideration of the principle of non-discrimination on the grounds of religion. The CJEU ruled that a business’s internal policy which prohibits the visible wearing of any political, philosophical or religious signs does not constitute direct discrimination, but is capable of constituting indirect discrimination.

The CJEU expressed the view that a policy of political, philosophical and religious neutrality is a legitimate aim to justify indirect discrimination. However a private company can only prohibit a religious sign, in this case a headscarf, on the basis of its neutrality policy, for those employees who are in visual contact with customers. If the employer decides that staff must have a neutral appearance, this policy must be applied in a coherent and systematic manner.

An employer must also consider whether employees who openly wish to wear religious symbols could be assigned to a different job, without any visual contact with customers. Finally the CJEU confirmed that a client’s demand for neutrality does not amount to an acceptable occupational requirement.

Facts of the cases

The case of Achbita (Centrum voor gelijkheid van kansen en voor racismebestrijding v G4S Secure Solutions NV (C-157/15)) was referred to the CJEU by the Belgian Court of Cassation, and the case of Bougnaoui (Association de défense des droits de l’homme (ADDH) v Micropole SA, formerly Micropole Univers SA (C-188/15)) by the French Court of Cassation. Both cases concerned women who were working in jobs which involved being sent out to work for client companies.

These women lost their jobs because of their refusal to comply with their employers’ request to take off their headscarves in their workplaces. Achbita started wearing a headscarf at work in her fourth year of employment. She was immediately confronted by her employer’s objection, based on the company’s “neutrality” policy. This policy was incorporated in the employees' code of conduct after the dismissal. Bougnaoui on the other hand was asked to remove her headscarf at work after the company received a complaint from a client, specifically that her veil had embarrassed certain employees.

Achbita was much anticipated, due to the state of uncertainty that was created by the national case law on the issue of whether a commercial private employer could invoke a neutrality principle to prohibit the wearing of any religious (but also philosophical and political) sign. Neutrality has been accepted as a ground for rights restrictions when applied to the public sector, under certain conditions, for example the respect of the principle of proportionality: Ebrahimian v France [2015] ECHR 1041. But now it is increasingly invoked by private employers. Several lawsuits in Belgium have shown that the question was regularly an issue of debate.

The important question that the CJEU had to answer was whether a private commercial employer – similar to a public administration – could prohibit the wearing of philosophical and religious symbols by employees, because they wished to be “neutral”.

The question for preliminary ruling in Achbita is legally important, as the possible justifications may vary depending on whether the underlying difference of treatment is directly or indirectly linked to religion and/or belief. Direct discrimination in the sphere of employment is almost impossible to justify, with the exception of a genuine and determining occupational requirement. The test is very strict: the required personal characteristic that is related to a discrimination ground should be indispensable in order to carry out the job: article 4 of Directive 2000/78/EC of 27 November 2000 establishing a general framework for equal treatment in employment and occupation.

Indirect discrimination allows for objective justification. The distinction must pursue a legitimate aim (the aim must not be unlawful), the means for achieving that aim must be appropriate and necessary (there should not be any reasonable alternatives), and the consequences must not be disproportionate: article 2(b)(i) of the same directive. The question for preliminary ruling in Bougnaoui was also important as it was seeking confirmation of the position in Firma Feryn (Centrum voor gelijkheid van kansen en voor racismebestrijding v Firma Feryn NV (C-54/07), 10 July 2008) on the weight to be given to customer preferences.

Advocate general opinions

Interestingly, Advocate General Kokott in Achbita and Advocate General Sharpston in Bougnaoui reached opposite conclusions in their opinions, based on diverging interpretations of several aspects of the EU directive. In short, for Kokott, there was no discrimination; for Sharpston, there was.

Kokott concluded that “the ban at issue applies to all visible religious symbols without distinction. There is therefore no discrimination between religions” (para 49). Kokott clarifies this point of view by stating: “That requirement of neutrality affects a religious employee in exactly the same way that it affects a confirmed atheist who expresses his anti-religious stance in a clearly visible manner by the way he dresses, or a politically active employee who professes his allegiance to his preferred political party or particular policies through the clothes that he wears (such as symbols, pins or slogans on his shirt, T-shirt or headwear)” (para 52).

Sharpston concluded otherwise: a general ban on the wearing of religious signs when attending the premises of those customers was direct discrimination on the basis of religion, because it referred directly to the manifestation of a religious belief. The fact that the ban applied to all religions and beliefs did not undermine this conclusion (cf paras 87-89). Bougnaoui was treated less favourably on the ground of her religion than “another would have been treated in a comparable situation. A design engineer working with Micropole who had not chosen to manifest his or her religious belief by wearing particular apparel would not have been dismissed” (para 88).

Sharpston reviewed the prohibition of discrimination in EU law and concluded that it must, in the same way as all legislation, be applied in a way that is effective (para 72). Kokott also referred to previous case law of the CJEU (para 44*) and underlined that the CJEU generally had adopted a broad understanding of the concept of direct discrimination, and had always assumed such discrimination to be present where “a measure was inseparably linked to the relevant reason for the difference of treatment” However Kokott defended her opinion by arguing that “all of those cases were without exception concerned with individuals’ immutable physical features or personal characteristics – such as gender, age or sexual orientation – rather than with modes of conduct based on a subjective decision or conviction, such as the wearing or not of a head covering at issue here” (para 45).

| * For example, the judgments in Dekker (C‑177/88, EU:C:1990:383, paras 12 and 17), Handels- og Kontorfunktionærernes Forbund (C‑179/88, EU:C:1990:384, paragraph 13), Busch (C‑320/01, EU:C:2003:114, para 39), Kiiski (C‑116/06, EU:C:2007:536, para 55), Kleist (C‑356/09, EU:C:2010:703, para 31), Ingeniørforeningen i Danmark (C‑499/08, EU:C:2010:600, paras 23 and 24), Maruko (C‑267/06, EU:C:2008:179, para 72), Römer (C‑147/08, EU:C:2011:286, para 52) and Hay (C‑267/12, EU:C:2013:823, paras 41 and 44); see also, to that effect, the judgment in CHEZ Razpredelenie Bulgaria (C‑83/14, EU:C:2015:480, paras 76, 91 and 95). |

Kokott did however accept that the ban “is in practice capable of putting individuals of certain religions or beliefs... at a particular disadvantage by comparison with other employees,” constituting indirect discrimination that has to be justified (para 57). For Kokott neutrality is a legitimate aim, on the basis of the fundamental freedom to conduct a business. According to Kokott, further analysis must be made by the national courts, but she also indicated that the ban is appropriate and necessary to achieve the legitimate aim of neutrality, because other alternatives are not conceivable without presenting a disproportionate burden to the employer (paras 100-110).

Sharpston once again reached the opposite conclusion. Supposing the CJEU would consider the ban to constitute indirect discrimination, it was difficult for her to see how the prohibition could be found to be proportionate. For example when an enterprise has a policy requiring its employees to wear a uniform, it is not unreasonable to require employees to do as much as possible to meet this policy. An employer can therefore stipulate that those employees who wear an Islamic headscarf should adopt the colour of that uniform when selecting their headscarf (or the employer should propose a uniform version of that headscarf) (para 123).

Summary of the judgments

In Achbita the CJEU partially followed the opinion of Kokott. It held that there was no direct discrimination, because “the internal rule at issue… refers to the wearing of visible signs of political, philosophical or religious beliefs and therefore covers any manifestation of such beliefs without distinction. The rule must, therefore, be regarded as treating all workers of the undertaking in the same way by requiring them, in a general and undifferentiated way, inter alia, to dress neutrally, which precludes the wearing of such signs” (para 30).

The CJEU then continued to consider the matter of indirect discrimination, which is lawful under the directive if the measure is objectively justified by a legitimate aim and if the means of achieving that aim are appropriate and necessary.

It accepted “the desire to display, in relations with both public and private sector customers, a policy of political, philosophical or religious neutrality” as a legitimate aim. An employer’s wish to project an image of neutrality towards their customers related to the freedom to conduct a business that was recognised in article 16 of the Charter. It was, in principle, legitimate, notably where the employer involved in its pursuit of that aim only those workers who were required to come into contact with the employer’s customers (paras 37-38).

By adding the qualification “notably”, the CJEU does not exclude the possibility that neutrality could be legitimately invoked, but confines itself by explicitly stating that neutrality is a legitimate aim if it is applied to employees who have visual contact with clients.

The CJEU further considered the ban appropriate for the purpose of pursuing a policy of neutrality: “provided that that policy is genuinely pursued in a consistent and systematic manner” (para 40). These additional conditions were not considered necessary by Kokott. The CJEU seems to set the bar higher than Kokott did; only neutrality policies that are genuinely applied in a consistent and systematic manner are legitimate and appropriate.

Finally the CJEU ruled that the ban can be considered “strictly necessary” if two conditions are met. First, it should cover only the employees who visually interact with customers. Secondly, dismissal is allowed only if it is not possible (taking into account “the inherent constraints to which the undertaking is subject”, and without taking on an ”additional burden”) to offer the applicant a post not involving any visual contact with customers (paras 42-43). Unlike Kokott, the CJEU gives a strict interpretation to the necessity requirement, and suggests that employers should look for alternatives.

In the case of Bougnaoui, where the headscarf ban was not part of a general neutrality policy, but was based on client preferences, the CJEU ruled that this was a case of direct discrimination on grounds of religion. Direct discrimination can only be justified in the case of a “genuine and determining occupational requirement” (art 4(1) of the directive). The CJEU found direct discrimination on the ground of religion because: “the willingness of an employer to take account of the wishes of a customer no longer to have the services of that employer provided by a worker wearing an Islamic headscarf cannot be considered a genuine and determining occupational requirement” (para 41).

Conclusion

The Bougnaoui judgment is in line with previous case law ruling that client preference cannot be a genuine occupational requirement (Firma Feryn, above). The same conclusion cannot be drawn from the Achbita case: even though the CJEU has a tradition of a wide interpretation of direct discrimination, the CJEU chose a very formalistic approach in Achbita and concluded that there was no direct discrimination.

It is also questionable that the CJEU accepts neutrality as a legitimate reason to limit a fundamental right. Obviously a company can decide to have a neutral policy. But unlike the public sector, there is no legal obligation for private commercial companies to do so. The same restrictions cannot be justified, certainly where they involve fundamental rights. Companies do have the freedom to conduct a business, but this right is not absolute.

The difference between front and back office is also very vague. For example, what about an accountant of a private company who wears a headscarf and works in an open plan office, where at times clients are being welcomed? It is not her professional duty to be in contact with these clients. Is the fact that clients can potentially see her enough reason to say that she occupies a front office post?

A further question arises on the proportionality test. Should an employer allow neutral headgear, which does not express a religion but which meets the workplace dress code, such as a bandana or a hat? Reasonable accommodation for religious practices is not required by the EU directives in the clauses protecting against discrimination on the basis of religion, but the future will indicate the implications of the proportionality test in comparable cases.

It is now up to the national courts to pronounce a final decision taking into account these judgments. The French court is due to rule by September on Bougnaoui. Only time will tell what the impact of Achbita will be. In Belgium, for example, the decision gave an incentive to some employers such as Axa, a private bank [linked page in Flemish] to reaffirm their inclusive diversity policy, by clearly stating publicly that “employers should be themselves at work. That is what brings up their best talents”. The Achbita decision explains what is legally permissible, but it is important to emphasise that neutrality for private employers is not an obligation and that they are free to implement and apply their diversity policy in an inclusive way.

Published guidance for employers

The Equality & Human Rights Commission has published information on the issue of dress codes and religious symbols available here.

The Guidance states that if an employers want to implement a dress code or uniform policy, they must ensure that this does not directly or indirectly discriminate against employees with a particular religion or belief or no religion or belief. See our guide to the law to find out more about direct and indirect discrimination.

Any requests to change a workplace dress code or uniform policy must be considered separately as there may be clothing requirements that relate to some roles and not others. For example, wearing a religious symbol on a chain may be more of a health and safety risk when the employee’s role involves working with machinery with which it could become entangled than where their role is office based. For other roles there may be security justifications for not allowing an employee to wear clothing which makes it hard to verify their identity.

If you agree to a change in uniform policy on religious grounds for one person, you do not have to do it for everyone. It is not unlawful direct discrimination to treat people differently if their situations are different. For example, an employer agrees to a change in a uniform policy for a religious employee because otherwise they would be indirectly discriminating against that employee because of their religion. Another employee asks for the same change to the policy because they find the uniform uncomfortable. It would not be direct discrimination to refuse this request because this employee’s circumstances are not the same as the religious employee's, and the request does not relate to religion or belief or any other characteristic protected under the Equality Act 2010. The employer could also have refused the religious employee’s request if it was based on comfort alone.

In this issue

- Neutrality policies in commercial companies

- Court IT: the young lawyers' view

- Human rights: answering to the UN

- Galo and fair trial: which way for Scotland?

- Secondary victims in clinical negligence

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion: Alan W Robertson

- Book reviews

- Profile

- President's column

- Twin tracks to completion

- People on the move

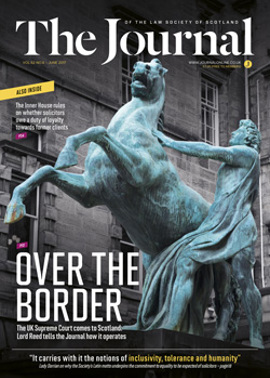

- Court of the nations

- Second time around

- How to avoid a summer tax scorcher

- Humani nihil alienum: a call to equality

- Sheriff commercial procedure: count 10

- Taking a pay cut: fair to refuse?

- Fine to park here?

- Enter the Bowen reforms

- Home grown

- Limited partnerships: a new breed

- Salvesen fallout: the latest round

- Gambling in football – the Scottish perspective

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Changing sides

- Business drivers

- CCBE comes to Edinburgh

- "Find a solicitor" gets an upgrade

- Law reform roundup

- Thoughts on a frenetic year

- Check those bank instructions

- Fraud alert – ongoing bank frauds identified

- AML: sizing up the risk

- Master Policy Renewal: what you need to know

- Without prejudice

- What's the measure of a ruler?

- Ask Ash