Salvesen fallout: the latest round

McMaster v Scottish Ministers [2017] CSOH 46 is the next chapter in the long running saga thus far comprising elements of the Agricultural Holdings (Scotland) Act 2003, the Salvesen v Riddell litigation, and the Agricultural Holdings (Scotland) Act 2003 Remedial Order 2014. The history will be well known to many, but a summary of the background follows, with a note on McMaster.

The past

Tenants under the Agricultural Holdings (Scotland) Act 1991 have security of tenure and the option of registering to create a pre-emptive right to buy. (The need to register in order to obtain this right will be removed when s 99 of the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016 commences.) In order to circumvent such security of tenure, a practice developed of leasing to a limited partnership in which the limited partner was the landlord and the general partner the party actually farming the land. If the landlord terminated the limited partnership, the tenant ceased to exist.

Elements of the 2003 Act sought to end this circumvention: a general partner could, by serving notice under s 72(6), become the tenant and so enjoy the benefits of the 1991 Act unfettered. In anticipation of this change, a number of landlords sought to terminate leases to limited partnerships.

A late amendment to the bill that became the 2003 Act effectively made an arbitrary distinction between landlords according to the date on which they had sought to bring the lease to an end, preventing some from serving an incontestable notice to quit on a former general partner who had become a tenant using s 72(6). Salvesen v Riddell challenged this on human rights grounds. The Supreme Court (2013 SC (UKSC) 236) held that the difference in treatment constituted a breach of article 1 to the First Protocol of the European Convention on Human Rights (“A1P1”). As such, that part of the 2003 Act was beyond the legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament. Consequently, the Remedial Order amended the Act to give all landlords to tenancies extended by s 72(6) notices the opportunity to serve an incontestable notice to quit.

McMaster

The petitioners in McMaster claimed that both the absence of any compensation provisions in the Remedial Order, and the ministers’ refusal to pay compensation, were unlawful because their A1P1 rights had been breached. A1P1 provides, inter alia, that there can be no deprivation of “possessions”, tempered by general exceptions such as control of use in the public interest.

Six sets of petitioners were heard, each representing a different farm. In each case landlords had sought to dissolve a limited partnership, and the general partner had served a s 72(6) notice to continue the tenancy after dissolution.

The Lord Ordinary (Clark) held that there could be a claim in principle for compensation, but only for “qualifying general partners (or joint general partners)” who had served a s 72(6) notice (para 152).

The court rejected the argument that all 27 petitioners, including family members of the general partners and certain partnerships or limited partnerships, had a claim. The general partners, having served s 72(6) notices, all had “possession” (in the odd language of A1P1) of their respective tenancies, but no link between those tenancies and the other petitioners was made out (paras 143-152).

On whether, in principle, compensation could be payable, the court began by determining the interference complained of to be a question of control of use, not deprivation of property (para 156), because the tenants had not been deprived of their tenancies by the Remedial Order. Rather, “an option” had been given to the landlords (para 157).

Considering whether A1P1 was violated, only the proportionality of the Remedial Order and lack of compensation were in contention. Ultimately, the court held that “the Remedial Order itself [my emphasis] did not violate the A1P1 rights of any of the petitioners” (para 172). Comparing the qualifying general partners’ present position with that pre-2003 Act, in effect those petitioners had gained an extended tenancy for which they had given nothing (para 180). Enhanced security of tenure had been gained and lost, but it was obtained under legislation which was unlawful (para 180). These factors militated against finding compensation to be necessary in pursuit of proportionality. However, there was another element: “in principle, in circumstances such as the present, the state should compensate individuals for loss directly arising from reasonable reliance upon defective legislation passed by it, which was then remedied by further legislation which interfered with the individuals’ rights under A1P1” (para 190). This is distinct from loss deriving from the termination of the lease, or from the loss of enhanced security of tenure.

The future

Whether, and how much, compensation is due to any of the general partners will require further proceedings. McMaster sets out a framework for analysis (paras 185, 190-192, and 195). Compensation would be payable “in respect of specific losses directly caused to the qualifying general partners as a consequence of reasonable reliance by them upon having a secure 1991 Act tenancy and for frustration and inconvenience, subject to the counterbalancing effect of setting off the value of the benefits obtained by [them] arising from the extended period of tenancy which was enjoyed” (para 195). No compensation would be payable for “any other consequences of termination of the tenancy” because had neither the 2003 Act, nor Salvesen, nor the Remedial Order existed, the tenancy would still have come to an end (para 192).

Some argument was made in McMaster that some of the general partners did not become tenants in their own right, for example due to (in)validity of the s 72(6) notices (para 136). As the court noted, these issues would need to be determined during any further hearings.

In this issue

- Neutrality policies in commercial companies

- Court IT: the young lawyers' view

- Human rights: answering to the UN

- Galo and fair trial: which way for Scotland?

- Secondary victims in clinical negligence

- Reading for pleasure

- Opinion: Alan W Robertson

- Book reviews

- Profile

- President's column

- Twin tracks to completion

- People on the move

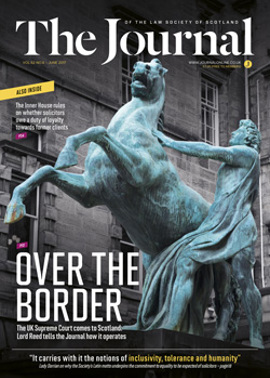

- Court of the nations

- Second time around

- How to avoid a summer tax scorcher

- Humani nihil alienum: a call to equality

- Sheriff commercial procedure: count 10

- Taking a pay cut: fair to refuse?

- Fine to park here?

- Enter the Bowen reforms

- Home grown

- Limited partnerships: a new breed

- Salvesen fallout: the latest round

- Gambling in football – the Scottish perspective

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Changing sides

- Business drivers

- CCBE comes to Edinburgh

- "Find a solicitor" gets an upgrade

- Law reform roundup

- Thoughts on a frenetic year

- Check those bank instructions

- Fraud alert – ongoing bank frauds identified

- AML: sizing up the risk

- Master Policy Renewal: what you need to know

- Without prejudice

- What's the measure of a ruler?

- Ask Ash