The clinical psychologist as expert witness in family law

Courts, social workers and solicitors often request expert psychological reports to aid decision making in complex family cases. The request is often for a “child psychologist”, despite this not being a regulated term. Subsequent instructions are commonly based on price or availability rather than on what any given expert can offer. Consequently, reports vary in approach, focus and detail.

In practice, clinical, forensic, educational and counselling psychologists may accept the expert role of “child psychologist”. While all will have shared psychological expertise, postgraduate training develops different skillsets, with continuing professional development leading to further divergence. We would argue it is crucial that when choosing an expert, decisions are informed by what question needs answered, with different psychologists bringing different expertise to the courtroom. Here we present a clinical model of psychological assessment designed to keep the child at the centre of the process.

The authors' approach is underpinned by contemporary attachment theory, and aims to assist the court through identifying key psychological components relevant to the child's psychological wellbeing. It is focused on understanding the child's experience and the quality of the parent-child relationship. It differs from some other approaches in that data are specific to the individual child, less reliant on population norms and quantitative data, but nonetheless informed by standardised assessments and established research, and dependent on expert assessment and analysis.

Primarily, when considering residential or contact arrangements (in public and private family law), what needs to be assessed is “the parents' ability to empathically understand and give priority to their child's needs” (Donald and Jureidini, 2004). Developments of attachment theory, most notably mentalization theory (e.g. Bateman and Fonagy, 2012), inform us that parents need to be able to reflect upon the mind of their child in order to respond sensitively to their child's behaviours and emotional needs. That is, to understand their child's feelings, thoughts and motivations, as separate to their own.

Parents are best able to do this when they are able to reflect upon and recognise how their own minds affect their capacity to parent. Successful reflective parenting promotes the child's social and emotional development and, more specifically, regulates the child's emotional state. Such parenting promotes a secure attachment relationship between the child and parent which works as a template for future successful relationships.

The less capable the parent at sensitively reflecting upon their child's and their own mind, the less able they are to offer parenting that promotes resilience and builds security in their child. As parental sensitivity decreases, the risk to the child's healthy psychological development increases. A severe lack of parental capacity to reflect upon the mind of their child is experienced by the child as frightening and has been referred to as interpersonal or attachment trauma (e.g. Allen, 2013). Parents who neglect or abuse their child usually lack the capacity to mentalize. The child, in turn, does not develop the ability to reflect upon themselves or the world and lacks a sense of self and social-emotional understanding.

Assessment process

Assessing the nature of the parent-child relationship is, therefore, central to our assessment process. Assessing the child's social and emotional understanding and ability to regulate their feelings provides insight into the extent to which the child's need for consistent reflective parenting has been met, and what they need in future parenting relationships. Assessing the parent's capacity to reflect upon their child's and their own minds provides insight into the parent's ability to be able to meet the challenges posed by their child's developmental needs and, where necessary, the parent’s ability to address their own intrinsic characteristics which impede their parenting capacity (Donald and Jureidini, 2004). Assessing parent-child interactions allows us insight into how a parent regulates themselves around the child and how they anticipate and respond to the child's mind.

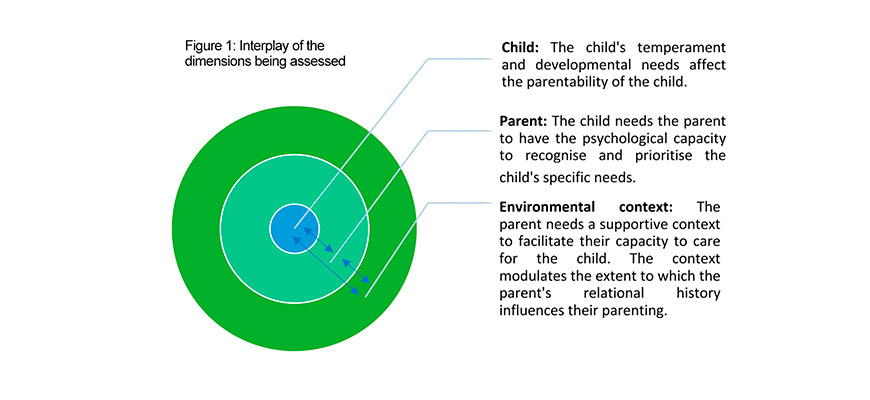

A parent's reflective capacity develops out of their past and ongoing life experiences. It is modulated by the needs of the specific child and the parent's environmental circumstances, as illustrated in figure 1. Assessment, therefore, also seeks to understand the impact of the context within which parenting takes place.

Parenting assessment frameworks, even those considered to be “best practice”, are often limited to gathering of information that is observable, self-reported or restricted to comparing parents to checklists of factors associated with protection or risk. Whilst such information is valuable, and may include reliable and valid quantitative psychometrics, making sense of the data requires post hoc subjective and untested interpretation of its relevance to the individual child or parent.

This process is usually informed by experienced professionals, and data can be triangulated, but it is important to recognise that externally gathered information about parents and children alone can be misleading. This is especially relevant for the most “at risk” patterns of attachment, where children and adults can behave in ways that mask what is going on. For example, a traumatised child may not present with any overt problems because they are relying on maladaptive coping strategies such as splitting off emotional pain; a parent might present as being able to offer a child a positive experience within time limited contact but not be able to maintain this full time.

Focus of analysis

The assessment process used by the authors seeks to go beyond externally gathered information to gain insight into the internal world of the child and the way parents think about their child's mind. The process includes use of rigorous and detailed assessments. They add child-centred psychological profiles to a report. Such assessments require additional training, with lengthy administration and scoring by use of video/audio recording and transcripts. The use of such tools places the child and the parent-child relationship at the centre of the assessment and subsequent opinion. The use of properly conducted validated assessment procedures allows for in-depth analysis and evidence-based assessment of risk in relationships.

The method of assessment in this approach requires assessment of parent, child, and parent-child interactions. The framework does not seek to diagnose whether the child or parent is suffering from a psychiatric or personality disorder. Such information does not facilitate understanding about the way the parent thinks about the child's mind, or the way in which the child's representations of themselves in the world are developing. The attachment theory-based framework of the assessment is orientated to understanding function: what the purpose of the behaviour is, and how it contributes to the child's, or parent's, overriding goal of staying safe and nurtured (Grey, 2019).

Part of any assessment must also be about the ability of that parent to change, or being assured that it is not other factors that are impacting on their capacity, for example domestic abuse, poor housing or a learning disability. Parents with learning disabilities are often discriminated against, not because of their capacity to meet the child's psychological needs, but their capacity to engage in universal services. It must also be recognised that parents with complex needs are likely to experience difficulties not only in building relationships with their child, but in maintaining relationships within personal and professional networks. This in turn impacts on their parenting ability.

This assessment process focuses on the parent's capacity to meet the needs of a specific child or children. It cannot always be generalised to other children, especially future children. A parent may feel overwhelmed by, or unable to attend to, the normal emotional and developmental needs of a given child due to specific factors in their relationship with that child. In some cases, a parent may be able to tolerate the normal demands of one child, but struggle to manage a child with additional needs, such as those caused by emotional trauma. Thus, a parent who has had a child removed in the past but who has made improvements enabling them to parent subsequent children, may still not be able to parent the child who was removed, due to the extensive psychological needs of that specific child.

Some experts choose or accept instruction only to assess parents; the Scottish Legal Aid Board will often only fund assessment of the parents. Thus, the specific psychological parenting needs of (sometimes multiple) children are never fully understood. This might be sufficient in some of the more straightforward cases, but in many of the complex permanence or high-conflict contact cases, where expert opinion is sought, omitting the needs of the child from any assessment process inevitably means the child is no longer at the centre of decision-making. Likewise, taking only the views of the child, outwith the context of their parental relationship, prevents understanding of how one influences the other.

To conclude, this article offers insight into our attachment-based assessment process to promote child-centred decision-making in the courts. There are a range of valuable expert approaches to assessment and it is important that these are understood and utilised depending on the needs of any given case, rather than by chance or professional protectionism.

References

Allen, J G (2013). Mentalizing in the development and treatment of attachment trauma. London: Karnac Books.

Bateman, A, and Fonagy, P (2012). Handbook of mentalizing in mental health practice. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Pub.

Donald, T and Jureidini, J (2004). "Parenting capacity". Child Abuse Review (13) 5-17.

Grey, B (2019). The Meaning of the Child Interview: Assessing the Nature of the Parent-Child Relationship from Semi-Structured Interviews with Parents. Unpublished Coding Manual: Version 3.

Perspectives

Features

Briefings

In practice

- Tradecraft – one solicitor's experience

- Dear employer...

- Team building – for the Foundation?

- Accredited paralegal practice area highlight: conveyancing

- Accredited Paralegal Committee profile

- What's new for paralegals?

- Ask Ash

- Managing the risk of workplace stress

- Appreciation: Iain Alexander Macmillan

- Revealed – by your AML certificates