Sport: Lessons from the Whyte review

In recent years, there have been enquiries in various sports and growing calls for independent reports, investigations and assessments of issues. In some instances, an independent and extensive review is essential.

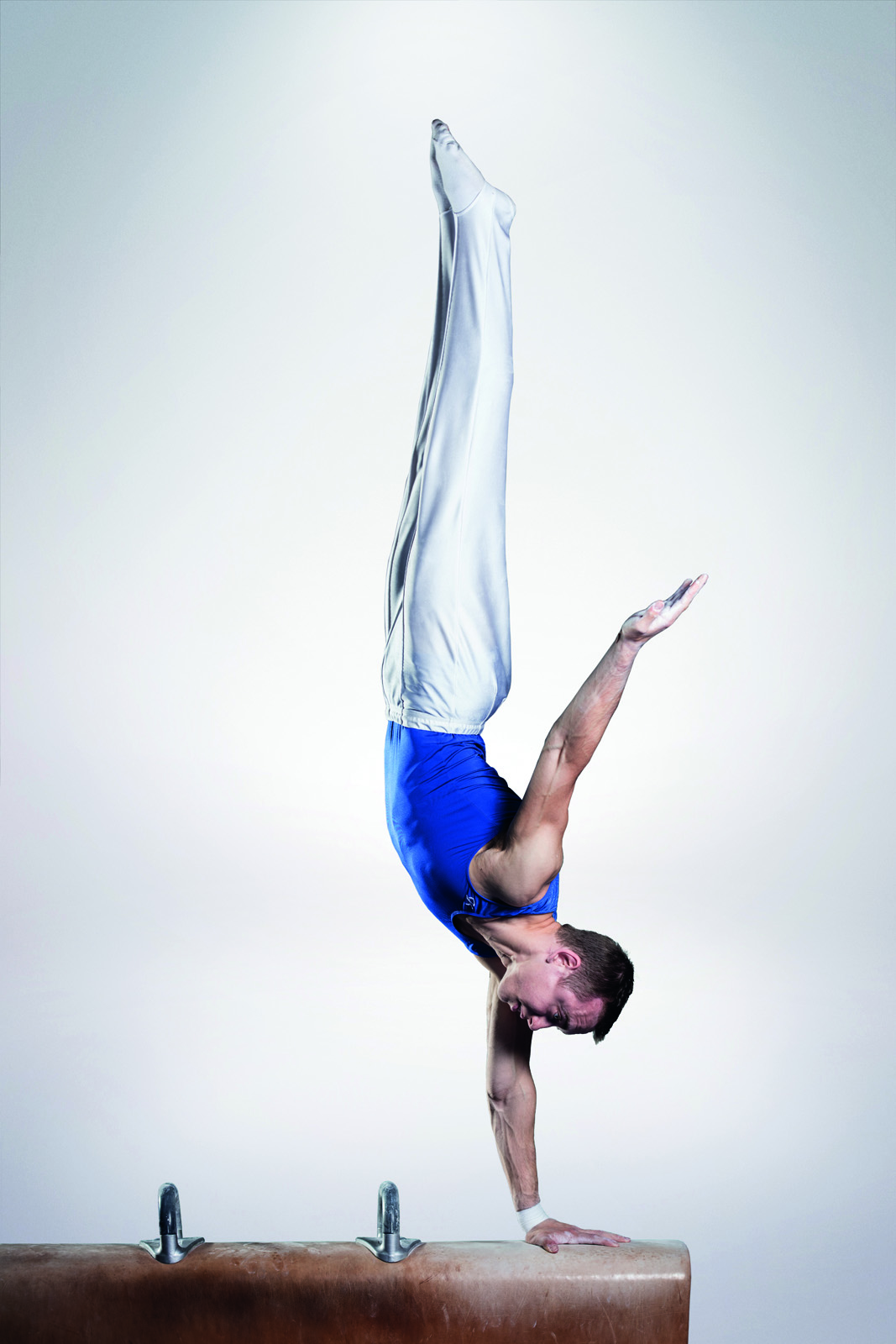

The Whyte review of gymnastics in England is one such example. Multiple allegations of emotional and physical abuse prompted an examination of whether British Gymnastics (“BG”) failed to prevent behaviours and preferred the pursuit of performance success; where welfare and wellbeing sat in BG’s culture (including clubs and coaches); whether safeguarding complaints had been dealt with appropriately; and whether persons had felt unable to raise complaints. Physical abuse complaints focused on chastisement, overtraining (with consequences), and withholding of food, water and access to the toilet. Emotional abuse ranged from shouting to excessive weight management.

Whyte found BG had paid insufficient attention to cultures within the sport, with coach-led environments, including in regional performance areas (rather than a closely monitored centralised one), and coaches lacking sufficient CPD. Safeguarding complaints and disciplinary issues were often dealt with in a less formal manner. Low-level complaints concerning poor practice were not properly scrutinised; inconsistency and inefficient handling were prevalent, before a dedicated safeguarding manager brought change. Within the performance environment, fears of deselection, demotion and loss of funding caused concern and put athletes off complaining, particularly given the coach’s essential role in their success. A lack of focus at board level on culture, safeguarding and welfare was found: a prevailing focus on commercial and other matters also contributed to cultural difficulties.

With recommendations including improved safeguarding courses and training, welfare provision for athletes, and education and standards being improved and reinforced, the Whyte review directed cultural change. Through recommendations for improved case management and independent panels overseeing complaint assessment, coupled with higher level board responsibility, Whyte called for improved governance arrangements, with independent, suitably experienced board members, a communication pathway with athletes, and more effective oversight from the board (by taking responsibility for implementation of the correct processes).

Lessons for other bodies

The Whyte report prompts the need for sports and sports practitioners to consider reaffirming knowledge and understanding of the seriousness of physical and mental abuse. The lasting impact of poor coaching behaviours on athletes should not be underestimated, and should be factored into the response of the sports body, shaping the institutional response and culture in addressing complaints. Low level complaints must be given formal attention for welfare within the sport to be prioritised and not overlooked in the pursuit of performance goals. Experience highlights that it can be difficult for complaints to be forthcoming (given the coaching relationship), but also a reluctance to become involved in a process where live evidence may be required and be challenged. Sports bodies can manage their proceedings to support welfare, manage risk and avoid quasi-judicial proceedings, with appropriate care, focused not only on the interests of the complainer, but carefully considering how to respect the interests of the person accused of perpetrating abuse.

Formal proceedings are not required where poor practice or conduct is admitted and guidance, training and sanctions are agreed.

An agreed disposal, to the sports bodies’ liking, will help reduce administrative resource and allow focus on improvements for the benefit of the athlete and sport alike. If cases are contested, care needs to be exercised if oral evidence is to be given; traditional cross-examination is often not permitted by sports procedural rules, but if an inquisitorial approach is followed by the expert panel examining the allegations, the evidence can be well tested. That may include questions posed, for the accused, through the chair.

While such an approach can be unpopular with defence agents, in private proceedings of this nature there is no inherent unfairness or unlawfulness in it. Stopping proceedings becoming aggressive and offputting to participants is essential, while allowing accused respondents to assert their position is important. Formal proceedings can be particularly daunting for persons who may have suffered or witnessed abuse, and while the rights of the accused must be balanced, the accused should be best judged by the expert panel interrogating the evidence and assessing it against the rules and their expert knowledge of the sport, safeguarding issues and the law.

While such an approach can be unpopular with defence agents, in private proceedings of this nature there is no inherent unfairness or unlawfulness in it. Stopping proceedings becoming aggressive and offputting to participants is essential, while allowing accused respondents to assert their position is important. Formal proceedings can be particularly daunting for persons who may have suffered or witnessed abuse, and while the rights of the accused must be balanced, the accused should be best judged by the expert panel interrogating the evidence and assessing it against the rules and their expert knowledge of the sport, safeguarding issues and the law.

A blend of experience is often invaluable in assessing whether there is a risk of harm and what response the sport should take. Punishment may not be the obvious or best approach, but is often necessary; changing behaviours, correcting practice and some possible reconciliation may often be keenly explored. Any person facing proceedings is of course entitled to a fair procedure, which observes the principles of natural justice and the rules of the sport in question. That typically equates to the right to present evidence and submissions; to have knowledge of and to be allowed the opportunity to comment on the evidence and submissions made to the decision-maker; and to a reasonable opportunity to present their case.

Regulars

Perspectives

Features

Briefings

- Civil court: Pointers to the future

- Intellectual property: Data mining for all

- Agriculture: The next land reform package

- Corporate: Developments and divergence in data

- Sport: Lessons from the Whyte review

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- Property: Registration – over a decade?

- In-house: The top team – three more years