Building families through surrogacy

On 29 March, the Scottish Law Commission and the Law Commission of England & Wales published their joint report, Building families through surrogacy: a new law (available at www.scotlawcom.gov.uk). The report and draft bill outline a new regulatory regime for surrogacy that offers more clarity, safeguards and support.

By placing the best interests of the child at the heart of reforms and introducing pre-conception screening and safeguarding measures for the surrogate and the intended parents, we can respect the shared intentions of the parties to the surrogacy arrangement by recognising the intended parents as the legal parents at birth. Our recommendations also have the effect that surrogacy will remain non-commercial, by prohibiting payments to the surrogate for carrying or delivering the child, ensuring that surrogacy agreements remain unenforceable, and requiring surrogacy organisations to operate on a non-profit-making basis. This article sets out the key recommendations in the report, which will now be considered by the UK Government.

The Commissions’ project

The Commissions’ joint review of the law of surrogacy was announced in 2018. In June 2019, we published our joint consultation paper, Building families through surrogacy – a new law (2019) Law Commission Consultation Paper No 244; Scottish Law Commission Discussion Paper No 167, setting out a range of provisional proposals. The consultation period ran for four months; we received 681 responses. We also held a series of public consultation events across the UK for people to discuss their views on our provisional proposals, and across the project there was a high level of engagement from consultees, whose responses have helped inform the recommended reforms.

What is surrogacy?

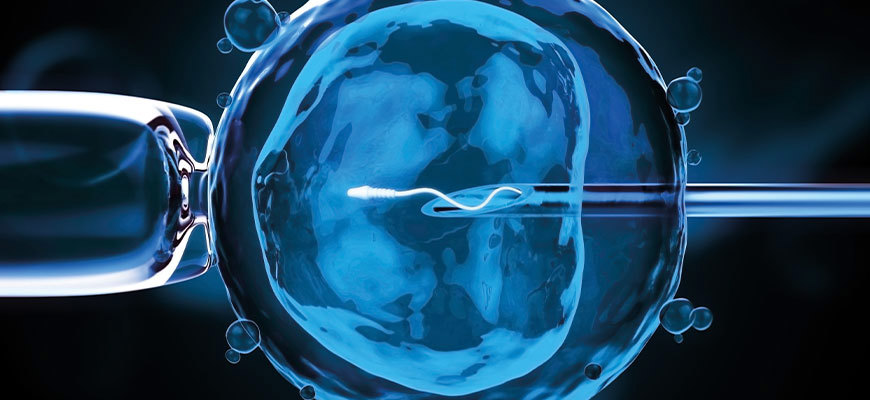

Surrogacy is when a woman (who we refer to as the surrogate) becomes pregnant with a child who may, or may not, be genetically related to her, and gives birth to the child with the intention that another couple or individual (the intended parents) will be the child’s legal parents.

A new pathway to legal parenthood

Under the current law, the surrogate is the child’s legal mother at birth, and the intended parents must apply for a parental order after the birth to become the legal parents. The current system produces several problems.

As a starting point, it does not reflect the intention of the parties involved in a surrogacy arrangement and does not serve the best interests of any of those involved. The surrogate, who does not intend to raise the child, is legally responsible for the child until the parental order is granted. During this time, the intended parents are not the legal parents and may not have parental responsibilities and rights, although they are usually the ones caring for the child and are best placed to take decisions about the child. The parental order process can take several months to complete and brings with it a degree of uncertainty and stress for the parties, which is not in the best interests of the child.

In response to these issues, we recommend the introduction of a “new pathway”, that will enable the intended parents to be the legal parents of the child from birth and remove the need to apply for a parental order. This new pathway will introduce essential screening and safeguards for the surrogate and intended parents prior to conception, so that state regulation comes before, not after, the birth of the child. These screening and safeguarding checks include health checks, a requirement to undertake implications counselling, independent legal advice, criminal records checks, and a pre-conception assessment of the welfare of the child.

We also recommend eligibility criteria, so that there must be a genetic link between at least one of the intended parents and the child, the parties must be domiciled or habitually resident in the UK, and the surrogate must be at least 21 years old. As at present, the intended parents must be at least 18 years old.

If these safeguards and eligibility conditions are met, the intended parents and surrogate will be eligible for admission to the new pathway. Importantly, the automatic attribution of legal parental status in favour of the intended parents will not affect the surrogate’s autonomy during the pregnancy: all decisions concerning the pregnancy and birth will remain with her. She will also have a right to withdraw consent during the pregnancy and for six weeks post-birth.

Non-profit oversight

To be admitted onto the new pathway, a surrogacy arrangement will need to be approved by a non-profit-making surrogacy organisation, which will be licensed and regulated by the Human Fertilisation & Embryology Authority (“HFEA”). We refer to these organisations as regulated surrogacy organisations (“RSOs”). RSOs will be the only bodies able to approve surrogacy teams to enter the new pathway and, in doing so, confirm that the required screening and safeguarding have been completed.

New rules on payments

The issue of payments is currently addressed in the context of parental orders. For a court to make a parental order, it must be satisfied that no money or benefit has been paid by the intended parents to the surrogate, other than “expenses reasonably incurred”: Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 2008, ss 54(8) and 54A(7). Yet this current test is unclear and has been interpreted broadly by the courts. Our recommendations are designed to provide clearer guidance, while guarding against exploitation and preventing the introduction of commercial surrogacy.

They take as their overriding principle that a woman should be no better or worse off financially from being a surrogate. We recommend that the law should not permit intended parents to pay the surrogate for carrying the child, compensation for pain and inconvenience, or general living expenses. Instead, the intended parents should be able to cover the costs of the surrogate pregnancy which fall in specific categories; and any payments which are not expressly permitted are prohibited. Permitted payments include:

- costs of meeting up in the period leading up to the surrogacy agreement, during the pregnancy and following the birth;

- medical and wellbeing costs;

- costs of pregnancy-related items, such as clothing or comfort aids;

- costs of additional food required as a result of being pregnant;

- costs of paying for assistance with household tasks, such as childcare or cleaning; and

- loss of earnings (whether someone is salaried or self-employed).

In addition to these permitted payments, which are entirely optional, there are some costs under the new pathway which the intended parents must pay, or offer to pay. These are the costs to the surrogate of medical assessment, counselling about the implications of the surrogacy agreement, and independent legal advice as to the effect of the new pathway, together with the costs of life and critical injury insurance.

Although surrogacy agreements should remain unenforceable, we recommend that the surrogate should be able to recover from the intended parents any costs which she has incurred that fall within the permitted categories and which they had agreed to pay her.

A new Surrogacy Register

At present, people born through surrogacy can find out about their gestational and genetic origins in several ways, such as from their birth certificate, court files from a parental order application, or the existing HFEA Register of donor conception. (The HFEA register was set up in 1991. A separate voluntary Donor Conceived Register helps to connect donor-conceived people who were conceived before 1 August 1991 with their donor and siblings.) However, there are gaps in the current framework because it was not developed with surrogate-born people in mind.

To address these gaps, we recommend creating a Surrogacy Register, to be maintained by the HFEA, alongside the existing HFEA Register of donor conception. The Surrogacy Register will record information for all surrogacy agreements entered into after the new law comes into force, whether in or outside the new pathway, and domestic or international. This will make it more straightforward for surrogate-born people to access information about their origins.

Reforms to parental orders

A parental order application will be needed where the surrogate has withdrawn her consent to the agreement proceeding on the new pathway. It will also be possible to apply for a parental order where the new pathway is not used, or for cases where the new pathway does not apply, such as international surrogacy arrangements. We therefore recommend a number of reforms to the parental order process, including that a late application for a parental order (beyond the statutory six-month period) should be permitted where this is in the best interests of the child. We also recommend that where the welfare of the child demands it, the court should be able to dispense with the requirement that the surrogate consent to the making of an order. This would bring parental orders into line with other family law where the welfare of the child throughout the child’s life is the paramount consideration.

What’s next?

Our draft bill applies in Scotland and in England & Wales. Our recommendations apply equally in both jurisdictions, subject to specific provisions in relation to matters such as parental responsibilities and rights, and succession, where we recommend surrogacy fitting into the existing Scottish provisions.

As surrogacy is a reserved matter, it is now for the UK Government to decide whether to introduce the bill, published with our report, giving effect to our recommendations. The Commissions’ view is that the reforms, if implemented, will improve outcomes for all parties involved in surrogacy and provide long overdue clarification and certainty to the surrogacy process as a whole.

Perspectives

Features

Briefings

- Criminal court: Towards proper control

- Planning: NPF4 – an emerging housing issue

- Insolvency: Court confirms overseas winding up approach

- Tax: R&D relief – welcome changes but outlook uncertain

- Immigration: Family reunions given new rules

- Scottish Solicitors' Discipline Tribunal

- In-house: Support to suit